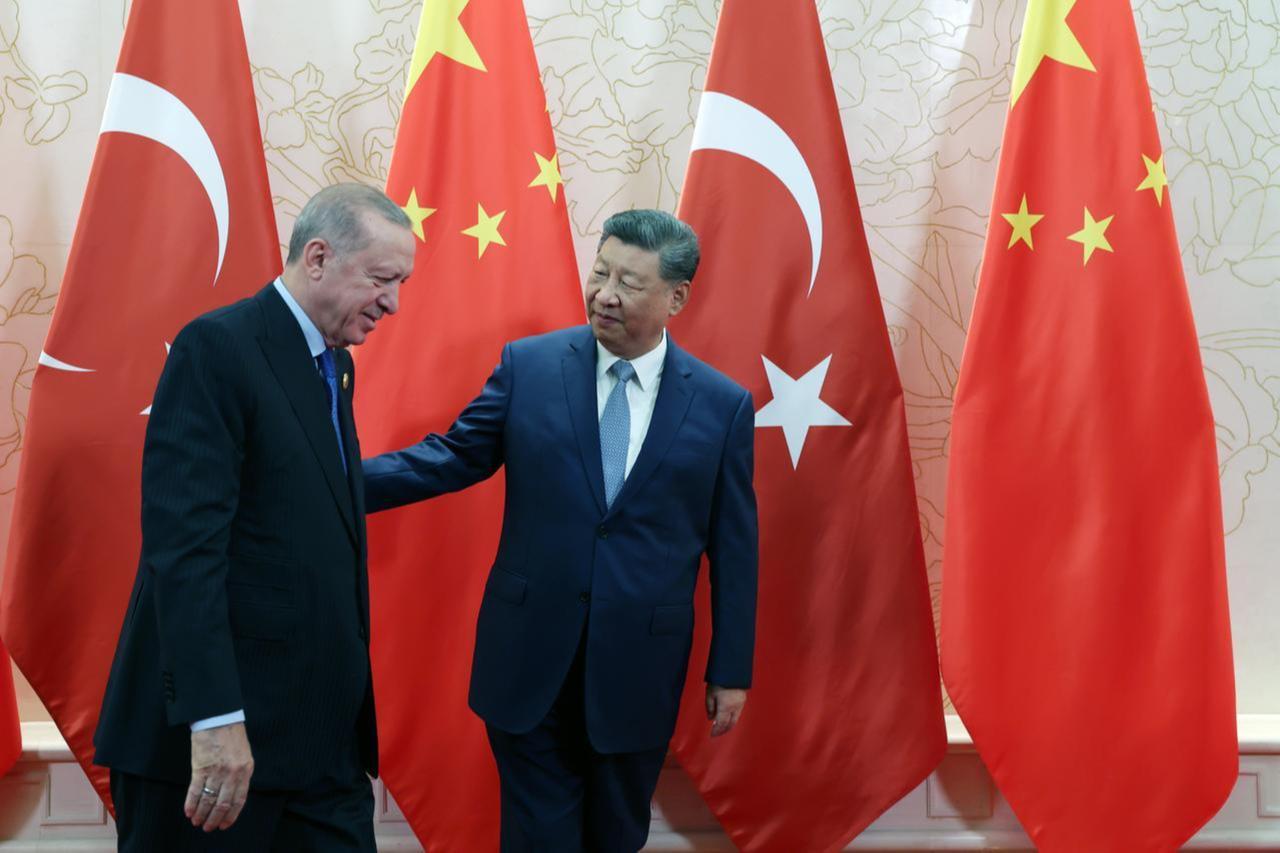

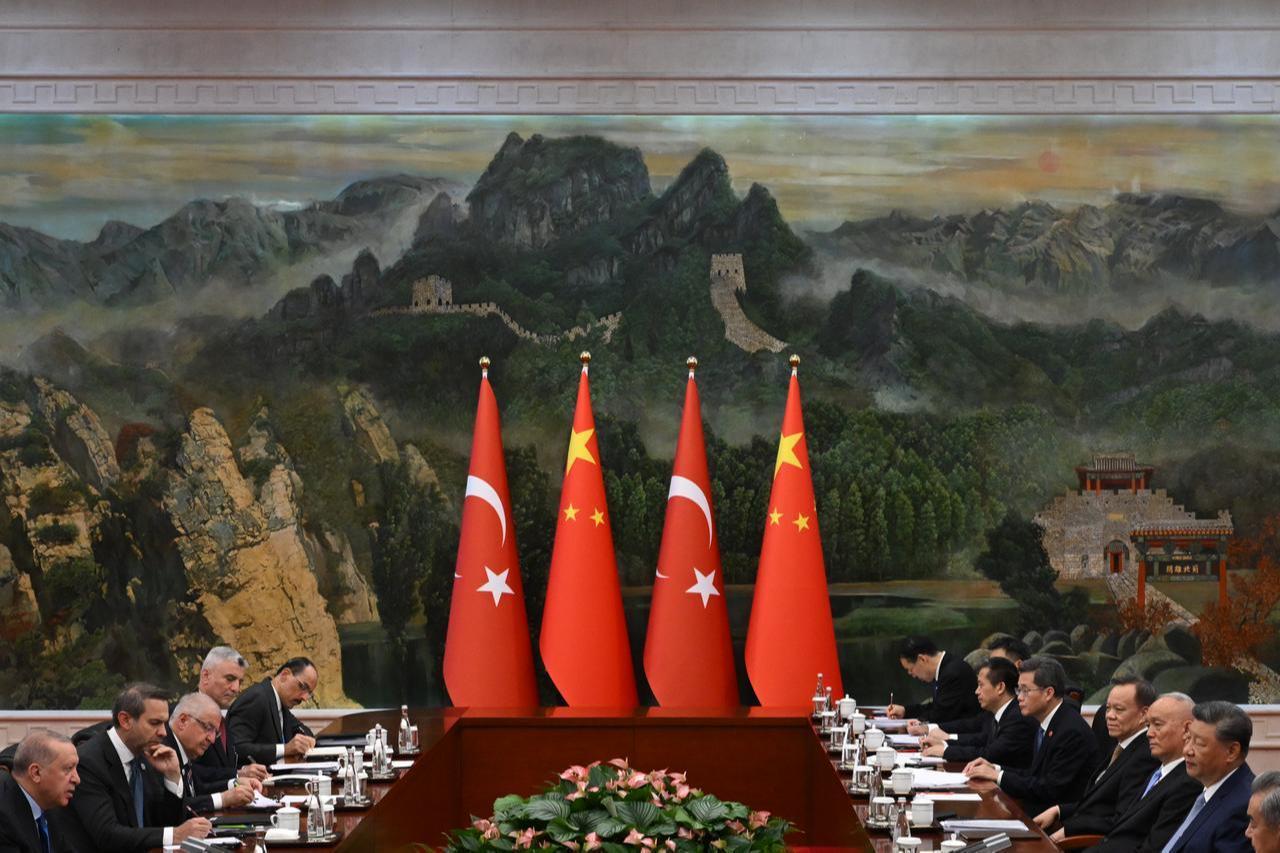

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Sunday during the 25th Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Tianjin. Türkiye, which has been a dialogue partner in the SCO since 2012, used the summit to advance both bilateral and multilateral goals.

At the core of discussions was the alignment of Türkiye’s Middle Corridor project with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Erdogan emphasized the need for “joint steps to harmonize the Middle Corridor and the Belt and Road Initiative,” according to Türkiye’s Communications Directorate. The Middle Corridor, designed to link Asia and Europe through the Caucasus and Türkiye, is seen as a strategic alternative to trade routes dominated by Russia.

The leaders also addressed pressing international issues, including the war in Ukraine, the crisis in Gaza, and potential coordination for rebuilding Syria. These conversations underscored how Türkiye positions itself as a state capable of addressing both global and regional crises while balancing its ties to the West and the non-Western world.

Türkiye’s involvement in the SCO was driven in part by tensions with Western allies in its earlier stages. Disputes over issues such as the S-400 missile system have periodically strained relations with the United States and Europe. Against this backdrop, Ankara seeks to balance its Western ties by demonstrating its ability to engage effectively with Eastern frameworks. This reflects a broader Turkish foreign policy reflex of pursuing multi-directional engagement, seen previously in initiatives like Türkiye’s Africa outreach.

Participation in the SCO also provided Ankara with an opportunity to highlight its security concerns. The organization’s focus on terrorism, radicalism, and separatism aligns with Türkiye’s domestic struggles against the PKK and the FETO terrorist organizations. By engaging in this forum, Türkiye found common ground with member states that also define their own internal threats as terrorism, creating opportunities for tactical cooperation.

In the new era of diplomacy after the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the second Trump term in the U.S, however, the meaning and the nature of that engagement have changed.

At its core, Türkiye’s approach to its Eurasia strategy centers on building connections without creating dependencies, a principle that also applies well to its relations with China. Ankara seeks to cultivate partnerships across regions while avoiding reliance on any single power. This approach enables Türkiye to identify itself as part of the West through its NATO and EU ties, while simultaneously presenting itself as part of the non-Western and Global South.

This dual identity offers flexibility. By being anchored in the Western security architecture, Türkiye reassures its allies of its commitments. At the same time, by engaging with China, Russia, and developing nations, Ankara signals its intention to diversify and align with a broader spectrum of global actors. This positioning strengthens its bargaining power and elevates its role in shaping discussions on multipolarity.

Beyond security, the SCO offers Türkiye exposure to major economic projects centered on China. Beijing’s BRI remains one of the most ambitious connectivity projects in the world, and Türkiye has positioned itself as a critical hub linking Asia to Europe. By staying active in SCO-related platforms, Ankara reinforces its economic agenda and ensures it remains a relevant actor in regional infrastructure and trade discussions.

During their bilateral meeting, Erdogan stressed that bilateral trade must be “supported by investments to ensure its balance and sustainability.” He encouraged more Chinese companies to expand into Türkiye, citing opportunities in digital technologies, healthcare, energy, and tourism. Both leaders agreed to strengthen institutional consultation mechanisms, underscoring the growing structure of the relationship despite Türkiye’s NATO membership and China’s partnerships with Russia and Iran.

China, however, remains cautious in its geopolitical posture. Despite its military capabilities, Beijing largely avoids direct intervention in global conflicts. Instead, it focuses on economic influence and soft power, preferring stability and trade over confrontation. For Türkiye, this makes China a pragmatic partner in areas like infrastructure and commerce, even if political alignment remains limited.

An important element of Türkiye’s outreach is its alignment with calls for reform in global governance. Ankara has long argued that “the world is bigger than five,” criticizing the U.N. Security Council’s current structure. This message complements China’s vision of a more inclusive global order where emerging economies and the Global South play stronger roles.

Türkiye’s emphasis on representation for non-Western voices resonates in multilateral forums. By linking its own demands for reform with Beijing’s advocacy of inclusivity, Ankara positions itself as both a regional player and a bridge for developing nations seeking greater influence in global decision-making.

Diplomatic engagements with China are not confined to structural debates. Türkiye is likely to raise regional crises, such as Gaza, during discussions, even if only behind closed doors. Ankara has consistently sought to frame the Gaza issue within its broader advocacy for global justice and the rights of the Global South.

Erdogan has gone further in public messaging. In an opinion piece published in People’s Daily, he described Israeli actions in Gaza as “brutality and genocide” and reiterated Türkiye’s support for “a fully independent and sovereign Palestinian state” based on the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital.

At the same time, Türkiye’s experience in managing the Ukraine war through “active neutrality” may feature in side conversations. By maintaining dialogue with both Moscow and Kyiv, Türkiye has already positioned itself as a mediator, and sideline meetings in Beijing could serve as stepping stones for future leadership-level dialogue. Such discussions reinforce Ankara’s ambition to act as a connector between conflict parties and global power centers.

Engagement with China and the SCO also serves Ankara’s ambition to act as a mediator and peace broker. Türkiye has repeatedly used its NATO membership alongside alternative partnerships to project itself as a country capable of talking to all sides. This approach, dubbed “active neutrality,” was particularly evident during the war in Ukraine, where Türkiye maintained dialogue with both Russia and Ukraine despite criticism from Western allies.

Such positioning has enhanced Türkiye’s diplomatic prestige, demonstrating that it can carve out independent influence within a multipolar system. By appearing in diverse international forums, Ankara reinforces its image as a balancing power rather than a subordinate actor within Western structures.

Erdogan used Chinese state media to highlight Türkiye’s diplomatic philosophy. Writing in People’s Daily, he portrayed Türkiye as a nation committed to building bridges and resolving conflicts through dialogue and fairness. He pointed to the Black Sea Grain Initiative and the renewal of talks in Istanbul in July 2025 as evidence of Ankara’s active role in global diplomacy.

“There are no winners in war and no losers in a fair peace,” he wrote, capturing Ankara’s message of mediation and pragmatism. By addressing Chinese audiences directly, Erdogan emphasized the “strategic dimension” of bilateral ties while reinforcing Türkiye’s role as a global connector.

While China is often portrayed as a rising superpower, its domestic challenges complicate its international reach. Significant income inequality persists between wealthy coastal regions and poorer inland provinces. Issues such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and rural underdevelopment continue to consume Beijing’s attention. The Communist Party’s emphasis on internal stability, censorship, and tight control over information reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of China’s governance model.

Despite being the world’s second-largest economy, China’s growth has not eliminated social disparities. Economic data remain opaque, and deep poverty is still visible in many areas. These internal pressures help explain why Beijing prefers to exercise influence through trade and investment rather than through collective security arrangements like NATO. For Türkiye, this means that China represents an opportunity in commerce but is unlikely to replace the West as a strategic anchor anytime soon.

Erdogan’s visit to China should be seen less as a pivot and more as part of Türkiye’s strategy of diversification, and not any type of substitution.

NATO remains central to Türkiye’s security, but engagement with the SCO and China broadens Ankara’s options in diplomacy, trade, and counterterrorism cooperation.

For Beijing, Türkiye is a valuable partner in its economic outreach, though domestic challenges limit its ability to reshape global security structures.

In this context, Türkiye’s outreach eastward complements rather than replaces its Western ties.