The quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) figures announced by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) this week showed that the Turkish economy sustained its growth for the 20th consecutive quarter with a 4.8% year-over-year rate, far above expectations. This came despite tight monetary conditions straining businesses and households and rising global uncertainty.

GDP is the total monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country over a specific period—usually a quarter or a year—and is widely used to gauge the overall size and health of an economy.

The rate offset the slower 2.3% expansion in the first quarter, with construction, industry, and trade sectors leading economic activity.

Thus, Türkiye ranked second among OECD countries, just behind Ireland’s unprecedented 18% boom. When major non-OECD economies are included, Türkiye ranks fifth, behind India, China, and Indonesia, respectively.

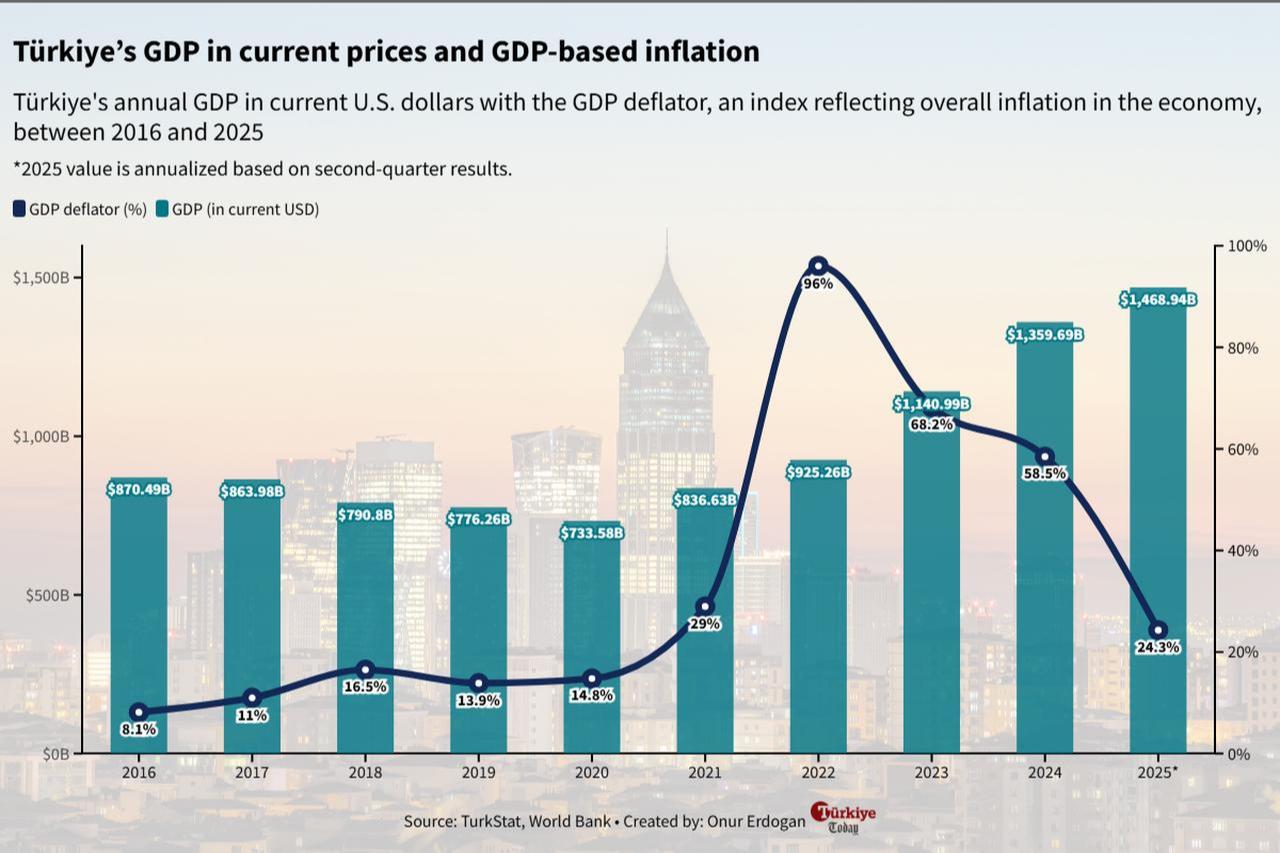

Over the last decade, from 2016 to 2025, the Turkish economy’s average growth rate was 4.8%, placing it fourth behind Ireland, China and India.

However, while the economy's expansion over the decade may seem impressive at first glance, it actually points to a harsher underlying reality. Since 2016, Türkiye's economy has faced a series of severe turbulences whose effects still continue to shape the economic agenda.

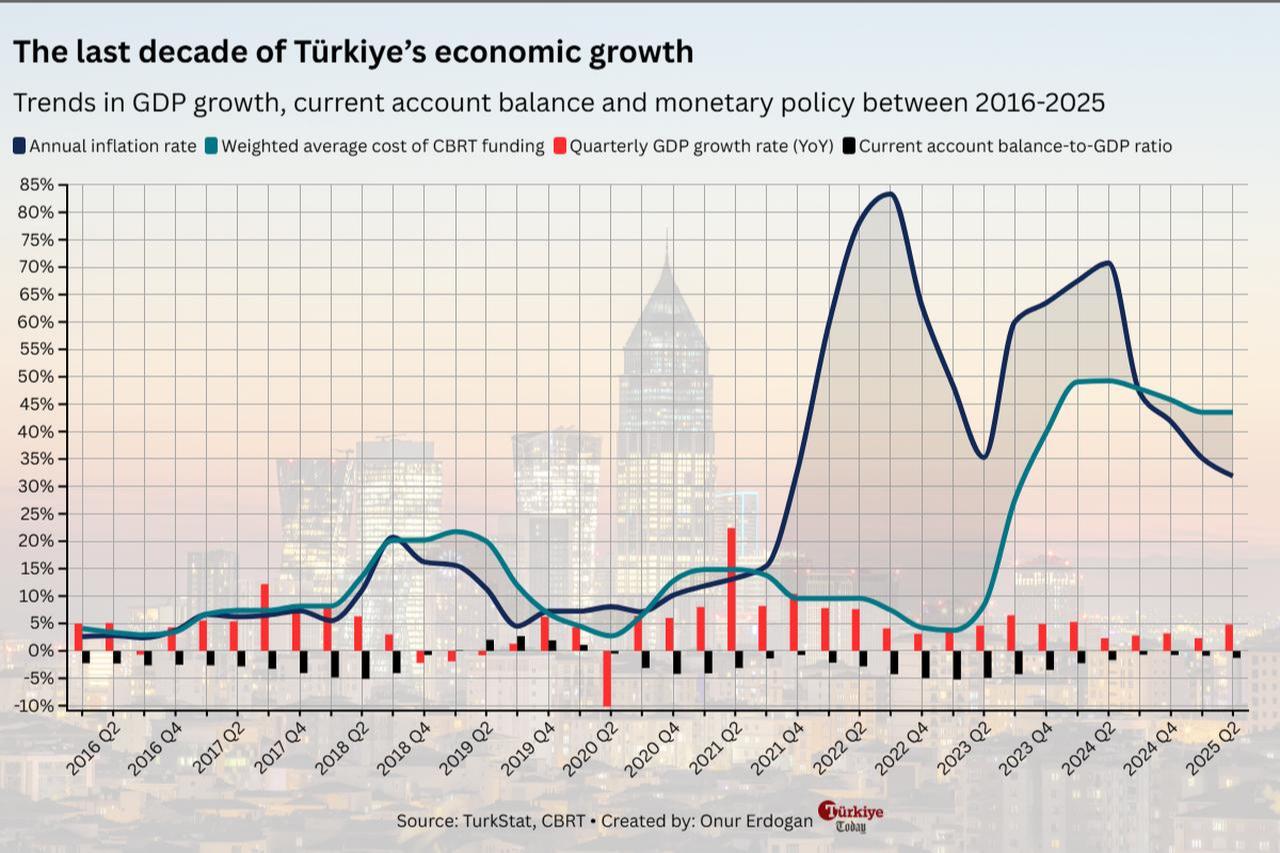

To tackle inflationary pressures and the widening current account gap that emerged after the July 15 military coup attempt and the first major currency fluctuation during the Pastor Brunson crisis with the U.S., the Turkish economic board pursued orthodox policies. These traditional measures like higher interest rates and tighter fiscal discipline aimed to bring down inflation, which had returned to double digits for the first time since the 2001 crisis.

Nevertheless, the tightness of monetary policy was seen as insufficient to grapple with inflation. An International Monetary Fund (IMF) mission stated in February 2018 that stronger monetary tightening, prudent fiscal management, and targeted structural reforms were needed to address overheating risks and rising vulnerabilities in the Turkish economy.

As the IMF noted, the Turkish central bank implemented further hikes in the policy rate, ensuring the required tightness in liquidity conditions to curb inflation. The hawkish stance of the central bank successfully brought headline inflation below double digits again, and Türkiye’s current account-to-GDP ratio returned to positive territory from a devastating -5.1% in 2018. Yet, the disinflationary policies were held responsible for the recession in 2019, when the Turkish economy contracted for three consecutive quarters and grew only 0.1% for the year.

After the headwinds of the 2019 contraction, Türkiye opted for growth over inflation amid fears that a loosening of sectoral activity could trigger a large-scale crisis and cause a sharp rise in unemployment, beginning to shape a new economic paradigm with heterodox policies that challenged conventional approaches. According to this view, favoring growth and job creation over strict inflation control—through low interest rates and expanded state-directed credit—was necessary to sustain economic momentum despite global and domestic woes. The policy also argued that inflation would be reduced primarily through greater state control in markets and by expanding supply, especially by boosting production.

Adding to the 2019 recession, the lockdowns during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic further deepened economic strains as the Turkish economy shrank by 10% in the second quarter of 2020, propelling the government to place greater weight on heterodox policies while almost completely abandoning orthodox ones in 2021.

As a result, the Turkish economy accelerated its recovery at an inimitable pace, reaching 22% in the second quarter of 2021. However, it also resulted in skyrocketing inflation of as much as 85%, as policymakers chose to keep interest rates below 10% to sustain this pace.

In the second quarter of 2023, Türkiye’s current account deficit-to-GDP ratio also hit 5.24%, the highest level in a decade. As high inflation further permeated costs and exerted pressure on production and pricing dynamics, the short-term advantage of Türkiye’s currency depreciation in international markets—which had boosted exports—was wiped out.

As the effect of costly relief measures that had allowed the Turkish economy to sustain its progress with overheated momentum faded, putting Türkiye in danger of a payments crisis, the government officially returned to orthodox policies under Mehmet Simdek, who stated, "There is no option left but orthodox policies that will ensure price stability, fiscal discipline, and sustainable growth."

The new economic approach embraced a time-spanning recovery from inflation and imbalances through gradual monetary tightening and tax reforms, rather than a "shock therapy" that would immediately suppress price hikes with a much tighter monetary policy and a full-scale austerity program. This was intended to prevent a steep recession that could wipe out the gains achieved during the economic boom.

As disinflationary effects became more apparent toward the second half of 2024, Türkiye’s economic growth showed a modest cooldown, with the expansion rate sliding to 3.3% in 2024 from 5.1% in 2023, slightly lower than the government’s Medium-Term Program forecast for 2025–2027. According to IMF estimates, GDP growth is expected to be 3.0% by the end of 2025, lower than the Medium-Term Program’s 4% target.

In an August interview with Reuters, Simsek also confirmed that economic growth would be slightly lower than expected by year-end. However, he emphasized that the government aims to ensure long-term stability with a balanced approach for sustainable growth rather than an overheated pace.

The economic board is also expected to unveil its updated Medium-Term Program for the 2026–2028 period on Sept. 8, to be presented by Vice President Cevdet Yilmaz. The program had previously targeted GDP growth of 4.5% in 2026 and 5% in 2027.