In the quiet residential street of Berggasse 19 in Vienna’s 9th district lies a portal not only to the past but also to the inner world of the human psyche.

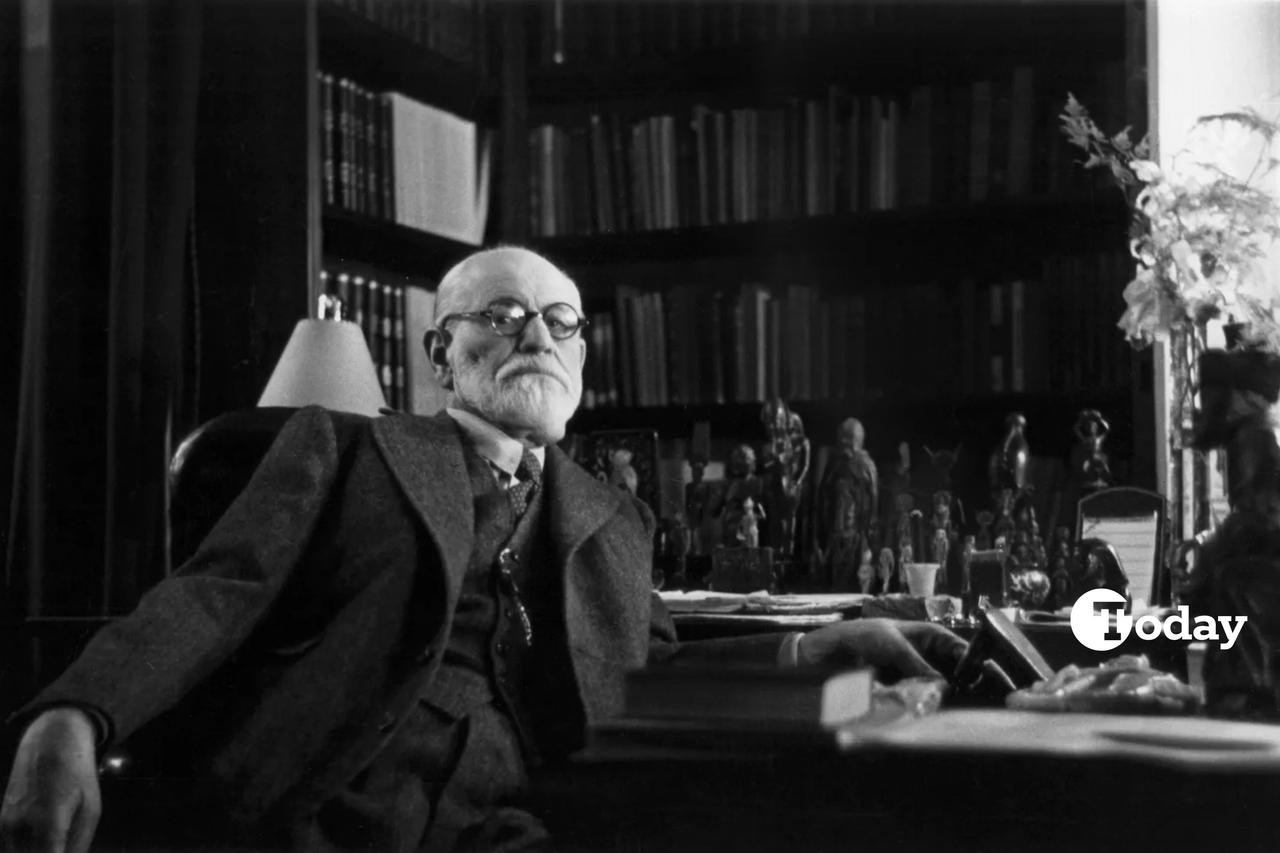

For 47 years, this address served as the home and workspace of Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis. Long before he fled the Nazis in 1938 and re-established his life in London, Freud was cultivating a space that blurred the lines between clinical science and symbolic ritual.

Freud’s office was more than a room. With its shelves of antiquities, shelves of ancient volumes, and walls covered with artifacts, it resembled an archaeological dig site. It was a carefully curated reflection of Freud’s belief that psychoanalysis was akin to archaeology—the slow, deliberate excavation of deeply buried mental content.

One of Freud’s most famous patients, Sergei Pankejeff—also known as the “Wolf” Man”—described Freud’s office as a sacred space, “a room that resembled not a doctor’s clinic but an archaeologist’s study.” And indeed, it was just that. The adjoining rooms, connected by a small door and looking out on a narrow courtyard, radiated a sense of serene introspection.

Inside were Egyptian stelae, Greco-Roman busts, Etruscan funerary jars, and Mesopotamian figurines—an eclectic museum of symbols. Each object resonated with Freud’s internal mythos, serving not just as decoration but as silent co-analysts in his work.

Freud often likened the act of psychoanalysis to archaeological excavation. In his 1896 paper “The Aetiology of Hysteria,” he compared the analyst to a discoverer arriving at ancient ruins, decoding half-buried tablets and forgotten languages to reconstruct lost memories. Like an archaeologist unearthing a lost civilization, the analyst must interpret fragments, reassemble collapsed structures, and, if successful, reconstruct a coherent narrative from the rubble of the unconscious.

The centerpiece of Freud’s consulting room was, famously, the couch. Covered with a richly patterned Iranian rug, the couch sat before a wall adorned with stelae, sculptures, and symbols. It was here that patients reclined to speak freely, embarking on mental journeys that paralleled the physical explorations of ancient tombs.

Some scholars have drawn attention to the uncanny resemblance between Freud’s office and an Egyptian burial chamber. Julia Schroeder, in her article “The Active Room: Freud’s Office and the Egyptian Tomb,” notes how both spaces allowed for bodily stillness while enabling psychic transformation. Just as the mummified body rested for its journey to the afterlife, the patient reclined in quietude to access buried thoughts and memories.

Freud never set foot in Egypt, yet his passion for its artifacts was lifelong. After his father died in 1896, Freud began collecting antiquities with increased intensity. By the time he relocated to London in 1938, his collection included over 2,000 items—half of which were from ancient Egypt.

In letters to friends and family, Freud wrote ecstatically of Assyrian kings with lions in their arms, winged human-animal hybrids, and vividly painted reliefs. In a letter to his friend Wilhelm Fliess, he wrote that Egyptian artifacts placed him “in a good mood” and seemed to whisper to him from distant times and places.

When Freud was forced to flee to London, he reassembled his sanctuary in his new home at 20 Maresfield Gardens. With the help of his architect son, Ernst Freud, he recreated the spatial arrangement of the Berggasse office, merging two rooms to restore the symbolic integrity of the space. Here, he spent his final days, surrounded by the objects that had witnessed decades of psychoanalytic discovery.

His ashes, as per the wishes of his family, were placed in an ancient Greek urn decorated with scenes of Dionysian revelry—a gift from Princess Marie Bonaparte. The urn had once been admired by Freud for its beauty and symbolism, and in death, it became the vessel for his final rest.

Though Freud never travelled to Egypt, he built his own temple in the heart of Europe—one that blurred the lines between science and myth, therapy and ritual, and life and death. His office was a place of transformation, where ancient symbols guided patients toward self-discovery.

In this sanctuary of memory and metaphor, Freud did not merely study the mind—he excavated it, layer by layer, like the ruins of an ancient civilization waiting to be reborn.