A new study combining archaeology and ancient DNA has revealed that the rise of farming in Anatolia—the region that is now modern-day Türkiye—was driven not only by migrating populations but also by local communities adopting new ways of life through cultural exchange.

Published in Science and led by researchers from Middle East Technical University (METU), Hacettepe University, and the University of Lausanne, the study brings a fresh perspective to one of prehistory’s major transitions: the spread of agriculture and village life.

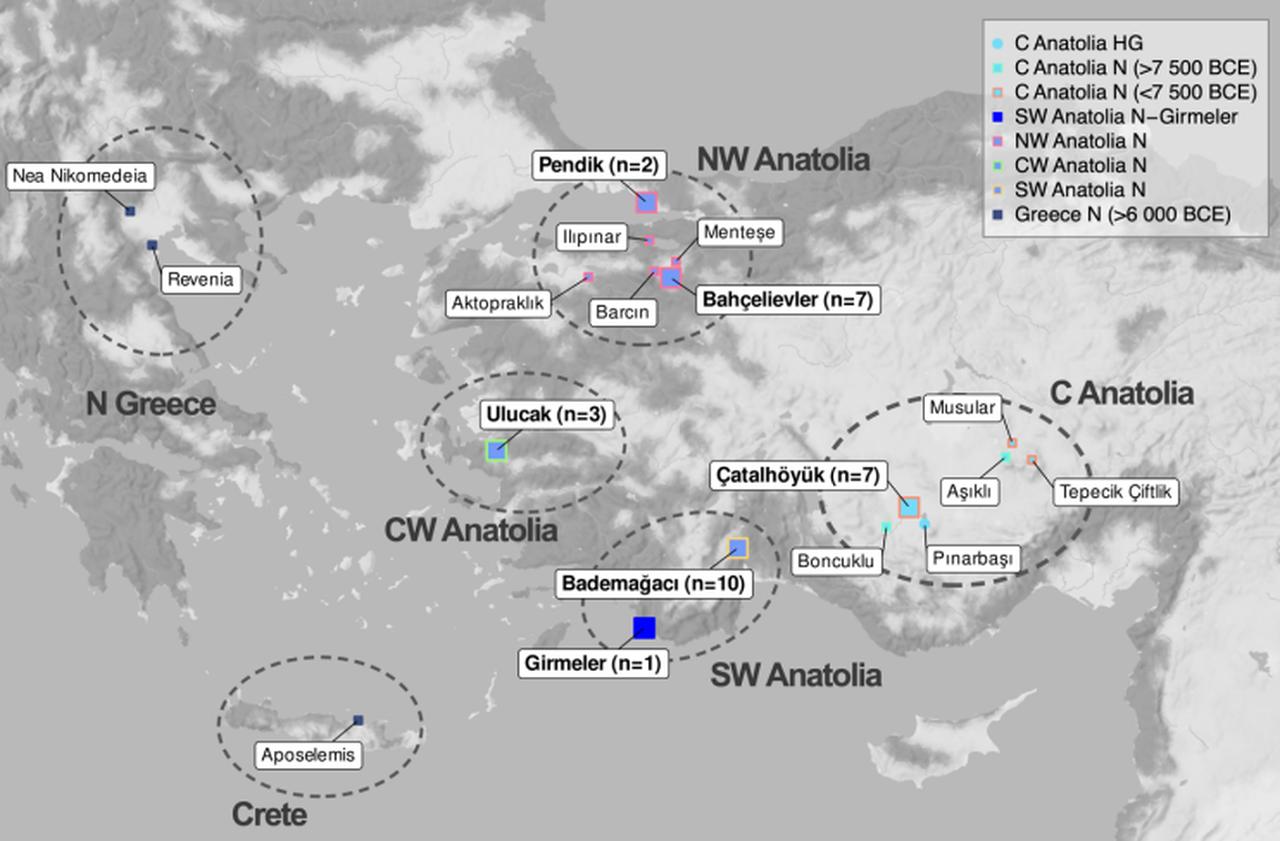

The team analyzed DNA from 30 individuals dating back to between 7,800 and 6,000 B.C., including the earliest genome ever sequenced in western Anatolia.

When these genetic records were compared with archaeological materials such as tools, pottery, and architecture, a pattern began to emerge: while farming practices and new technologies spread across Anatolia, local gene pools often remained surprisingly unchanged.

The research showed that in many parts of western Anatolia, early farming villages emerged nearly 10,000 years ago. Yet over millennia, the genetic make-up of these communities remained consistent, pointing to a scenario where local hunter-gatherers adopted farming rather than being replaced by incoming farmers.

Lead author Dilek Koptekin noted, "In some regions of West Anatolia, we see the first transitions to village life nearly 10,000 years ago. However, we also observe thousands of years of genetic continuity, which means that populations did not migrate or mix massively, even though cultural transition was definitely happening."

This finding stands in contrast with later periods in Europe, where genetic studies show that farming spread mainly through large-scale migration from Anatolia. The Anatolian model, instead, was more nuanced—some areas saw newcomers arriving and mixing with locals, while others transformed through ideas alone.

One of the most striking findings came from Ulucak Hoyuk, a site near Izmir in western Türkiye. While the community clearly adopted the “Neolithic package” of farming, house-building, and new tools around 6,700 B.C., their DNA remained largely local.

A similar story unfolded at Girmeler, a site in southwestern Türkiye, where a genome dated to 7,738–7,597 B.C. showed no signs of ancestry from neighboring farming regions such as Mesopotamia or the Levant.

This suggests that these communities transitioned to farming through long-distance cultural networks, not through waves of migrants bringing agriculture with them. Researchers found that even with strong influences from the east, these communities retained their local genetic signatures.

To understand how material culture spread, the researchers systematically coded and analyzed over 50 traits—such as building styles and burial practices—across 89 sites. The study revealed that cultural similarities often correlated with geography but not with genetics. In other words, people who used similar tools or built similar houses were not necessarily genetically related.

As Koptekin put it, “Archaeologists have this proverb, ‘Pots don’t equal people.’ Our study confirms this notion.”

In addition, computational analyses using tools like qpAdm and f4-tests showed that early Neolithic populations in Greece derived their ancestry mainly from Anatolian sources, rather than being local foragers adopting farming. Yet, the Anatolian migrants arriving in Greece appear to have mixed less with indigenous groups there compared to what occurred later in Europe.

While some Anatolian communities like those in northwest Türkiye did show signs of incoming populations and genetic mixing by 7,000 B.C., this was not the rule across the region. Genetic data indicated that migrations from central or southeastern Anatolia had varying impacts depending on the region. In many areas, the Neolithic transition was a patchwork of cultural adoption and occasional population movement.

The findings underscore how complex and regionally diverse the transition to farming was, even within a relatively small area like Anatolia. They also highlight the importance of large-scale collaboration between local archaeologists and international geneticists.

Ultimately, this research shows that technological and social revolutions in human history—like the shift to agriculture—did not always require large migrations. Ideas could travel further than people.

As computational biologist Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas concluded, "Genetically speaking, these people were mainly locals ... Yet their material culture evolved rapidly. This suggests that these communities adopted Neolithic practices by cultural exchange rather than population replacement."