Istanbul is a city built on layers of history. Above ground, Roman walls, Byzantine churches, Ottoman palaces, and modern buildings stand side by side. Beneath the streets, however, lies another Istanbul, an immense and largely unseen network of tunnels, cisterns, drainage systems, chambers, and secret passageways constructed over more than two millennia.

Like the unseen mass of an iceberg, this underground world has sustained the city above through empires, wars, earthquakes, and transformation, while remaining one of its most enduring mysteries.

Archaeologists and historians agree that hundreds of underground structures lie beneath Istanbul’s historic districts, particularly the Historical Peninsula, Beyoglu, Galata, Uskudar, and along the shores of the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus.

Many of these tunnels date back to the Roman and Byzantine periods, while others were expanded, repurposed, or concealed during the Ottoman era. New discoveries continue to emerge during metro construction, urban transformation projects, and large-scale restorations, revealing just how deeply the city is interwoven with subterranean passageways.

The earliest purpose of Istanbul’s underground network was largely practical. During the Roman and Byzantine periods, the city struggled with water supply, prompting engineers to develop an advanced system of aqueducts, cisterns, wells, and underground channels. These structures collected groundwater, distributed it across the city, and protected vital resources during sieges.

The most iconic example is the Basilica Cistern, built in the sixth century under Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. Covering an area of 9,300 square meters, it was capable of supplying the city with water for months if aqueducts were destroyed. Its survival through at least 25 major earthquakes stands as a testament to Roman engineering precision. Similar cisterns and water tunnels were later incorporated into Ottoman infrastructure, although the Ottomans favored flowing water over stagnant reserves, gradually shifting the function of many underground spaces.

Regarding the secret tunnels of Istanbul, Satiroglu (2018) argues that these subterranean structures, which are frequently revealed during modern excavations, form a vast, interconnected system shaped by successive civilizations, each adapting the tunnels to its own needs for water, security, and survival. This layered reuse explains why corridors often branch unpredictably, terminate abruptly, or connect to cisterns, palaces, and religious structures across the city.

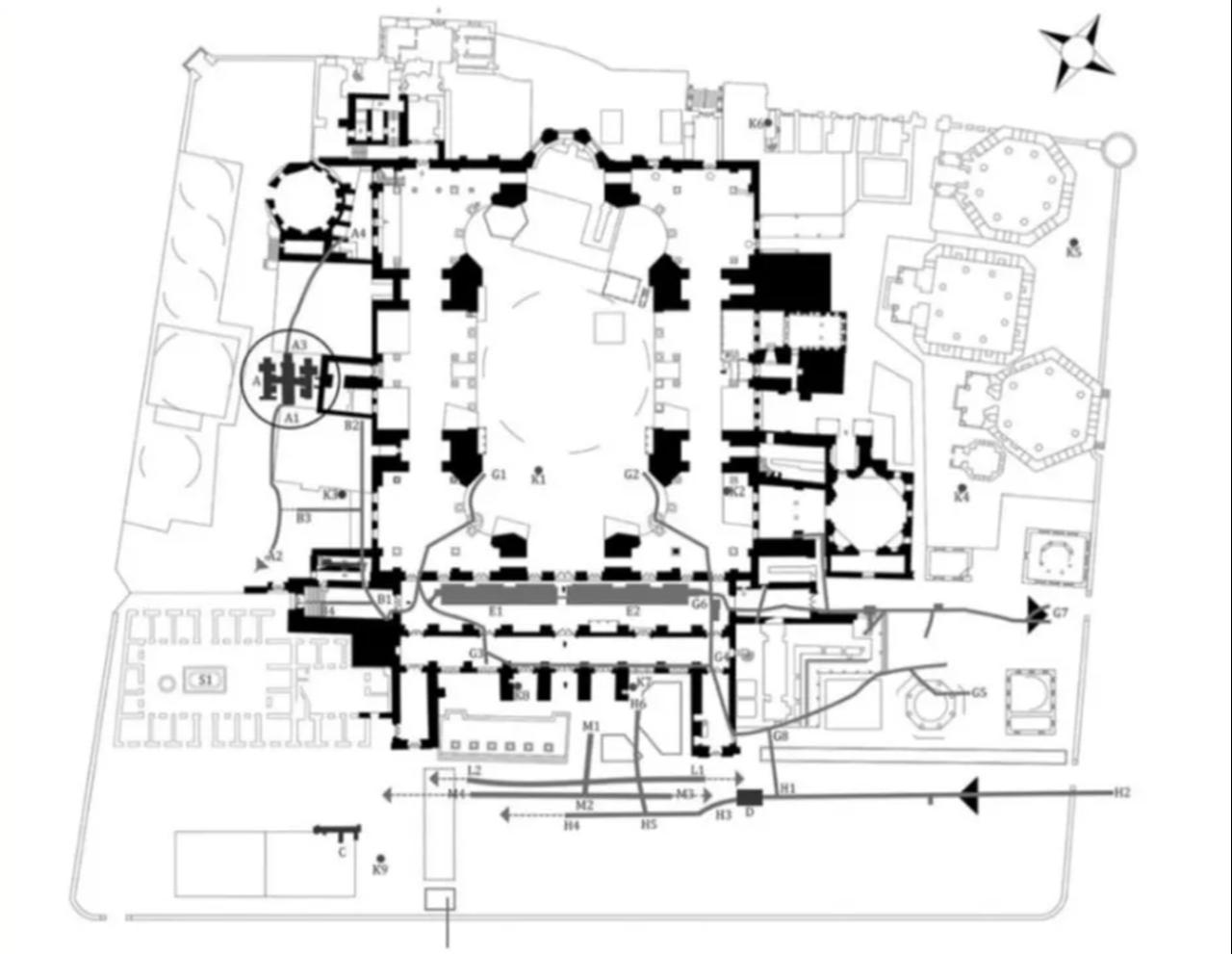

Few places illustrate Istanbul’s underground complexity more vividly than Sultanahmet Square. Once the Roman and Byzantine Hippodrome, this area served as the ceremonial and political heart of the city for centuries. Beneath the square and surrounding landmarks, including Hagia Sophia, researchers have documented extensive corridors, chambers, and water-filled passageways.

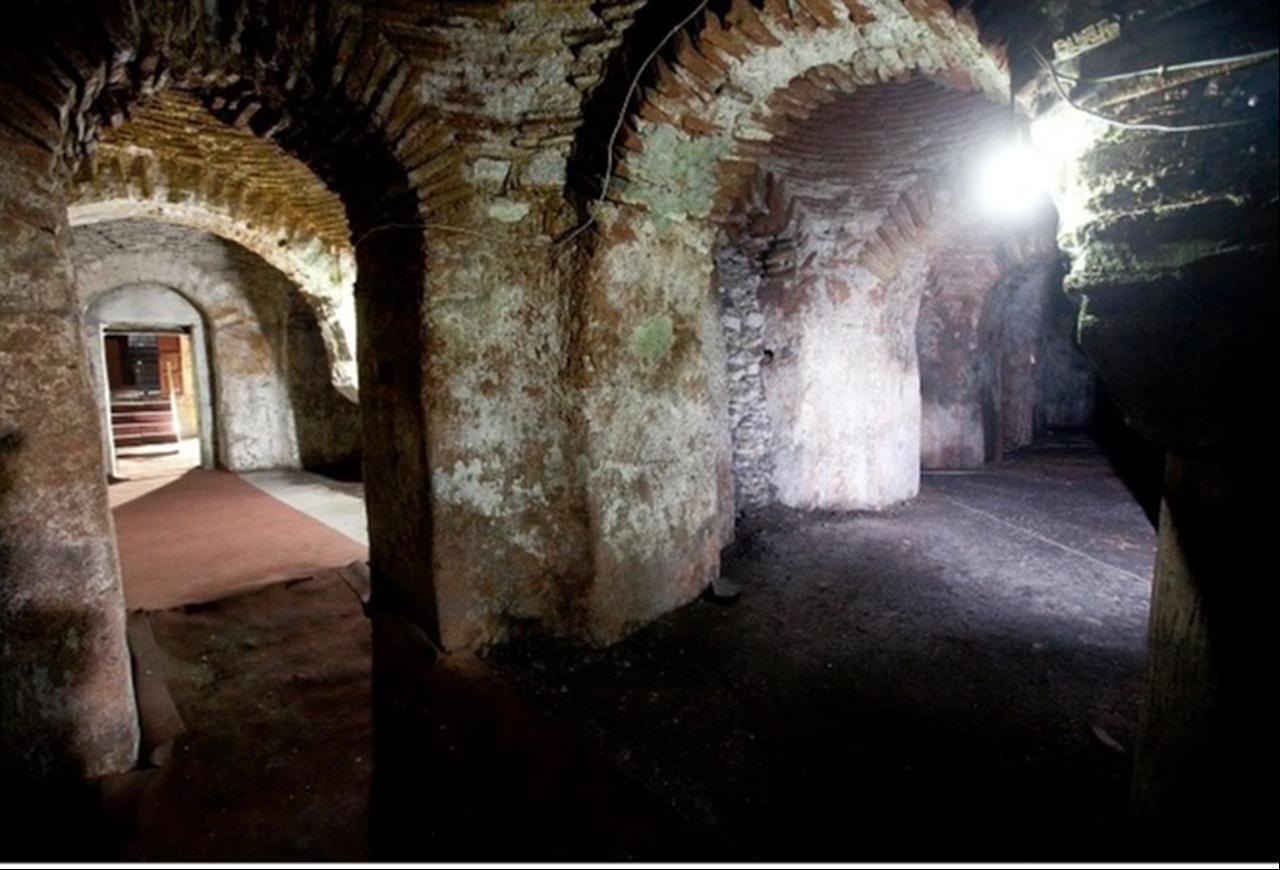

CNN Turk crews who entered the tunnels beneath Sultanahmet reported massive brick walls, dark corridors, spider colonies, sealed chambers, and water-filled routes that once required boats to traverse.

Some sections were later converted into cisterns by the Ottomans, while others were blocked off entirely, preserving unanswered questions about their original purpose.

The tunnels beneath Hagia Sophia have recently become a focal point of renewed scientific attention. Ongoing restoration and structural reinforcement efforts have revealed a labyrinth-like underground network exceeding 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) in length. According to Professor Hasan Firat Diker of the Hagia Sophia Scientific Committee, these corridors primarily served water distribution, ventilation, and rainwater drainage, rather than public movement.

In many sections, the passages are so narrow that crawling is required, indicating that they were designed for maintenance specialists rather than regular use. Some of these underground areas are expected to open to the public under a reservation-based system, offering controlled access while protecting the structure. Experts emphasize that making these spaces visible not only preserves them but also dispels centuries-old myths surrounding secret escape routes.

Despite scientific findings, legends continue to surround Istanbul’s underground world. Stories speak of tunnels connecting the Basilica Cistern to Topkapi Palace, Hagia Sophia, the Grand Bazaar, and even the Princes’ Islands. While some of these claims have been disproven through research, others remain unresolved due to sealed entrances and incomplete mapping.

According to Arslan (2024), the secret passages of Istanbul reveal how the city’s layered history produced an underground network that blends practical infrastructure with enduring myths, many of which persist because countless entrances have been sealed while others remain undiscovered. Treasure hunters, security concerns, and urban development have contributed to the closure of many access points, deepening the aura of mystery.

During the Byzantine era, tunnels beneath the Great Palace and Hippodrome were believed to serve as escape routes for emperors and as hidden corridors for palace staff and guards.

After the Ottoman conquest in 1453, Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror ordered the construction and expansion of tunnels in strategic areas such as Yedikule, Ayvansaray, Fatih, and along the Golden Horn. Known as lagim, these passages were often disguised as sewers to conceal their military function.

One of the most significant recent discoveries occurred at Rumeli Hisari, the fortress built in 1452 to control the Bosphorus. During restoration work in 2021, a 125-meter-long underground passage was uncovered beneath the coastal side of the fortress.

Officials believe it functioned as a medieval defensive structure for water drainage and military movement, possibly branching into additional corridors. Further studies suggest there may be several more tunnels in the area, many of which were destroyed during earlier road construction.

In the Ottoman period, underground tunnels also played a critical role in administration and security. Beneath the Public Debt Administration building, now Istanbul Boys’ High School, tunnels were used to transport money and valuables securely. These passages connected to the Basilica Cistern and the Sirkeci Post Office, converging near Sarayburnu. Today, they are sealed with steel doors to protect both their historical significance and the school above.

Other tunnels served unexpected purposes. During the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II, a passage was constructed between the Haydarpasa medical school and Karacaahmet Cemetery to transport cadavers discreetly for anatomy studies, which were controversial at the time. These sealed tunnels remain one of the most striking examples of how underground spaces contributed to scientific advancement.

In Beyoglu, restoration projects have uncovered tunnels beneath historic apartment buildings and inns. One notable example is Rumeli Han on Istiklal Street, built in 1894 by Saricazade Ragip Pasha. Rumored to be connected to nearby inns via secret tunnels, the building’s 1,400-square-meter cellar is now being restored for cultural and artistic use.

Nearby, restoration work at Galata Tower revealed dungeons and tunnels containing human remains, suggesting its use as a prison during the Ottoman period. Similar discoveries across Karakoy and Sishane throughout the 20th century prompted authorities to seal many entrances to protect the sites from damage and exploitation.

Claims that Istanbul’s tunnels extend beneath the Bosphorus, or even across Europe to Scotland, remain speculative, blending archaeological findings with legend. While such ideas continue to fascinate researchers and the public alike, experts emphasize the importance of distinguishing between documented history and myth.

What is beyond dispute is that Istanbul’s underground world forms a vast, interconnected system shaped by necessity, ingenuity, and power. As scientific research and restoration efforts continue, the city beneath Istanbul is slowly emerging from the shadows, not as a repository of hidden treasure but as a testament to human resilience and adaptation across centuries.

As millions walk Istanbul’s streets each day, few realize that beneath their feet lies another city, still waiting to be fully understood.