Archaeologists in Israel have made a groundbreaking discovery that challenges long-held beliefs about gender roles in early Christian monasticism.

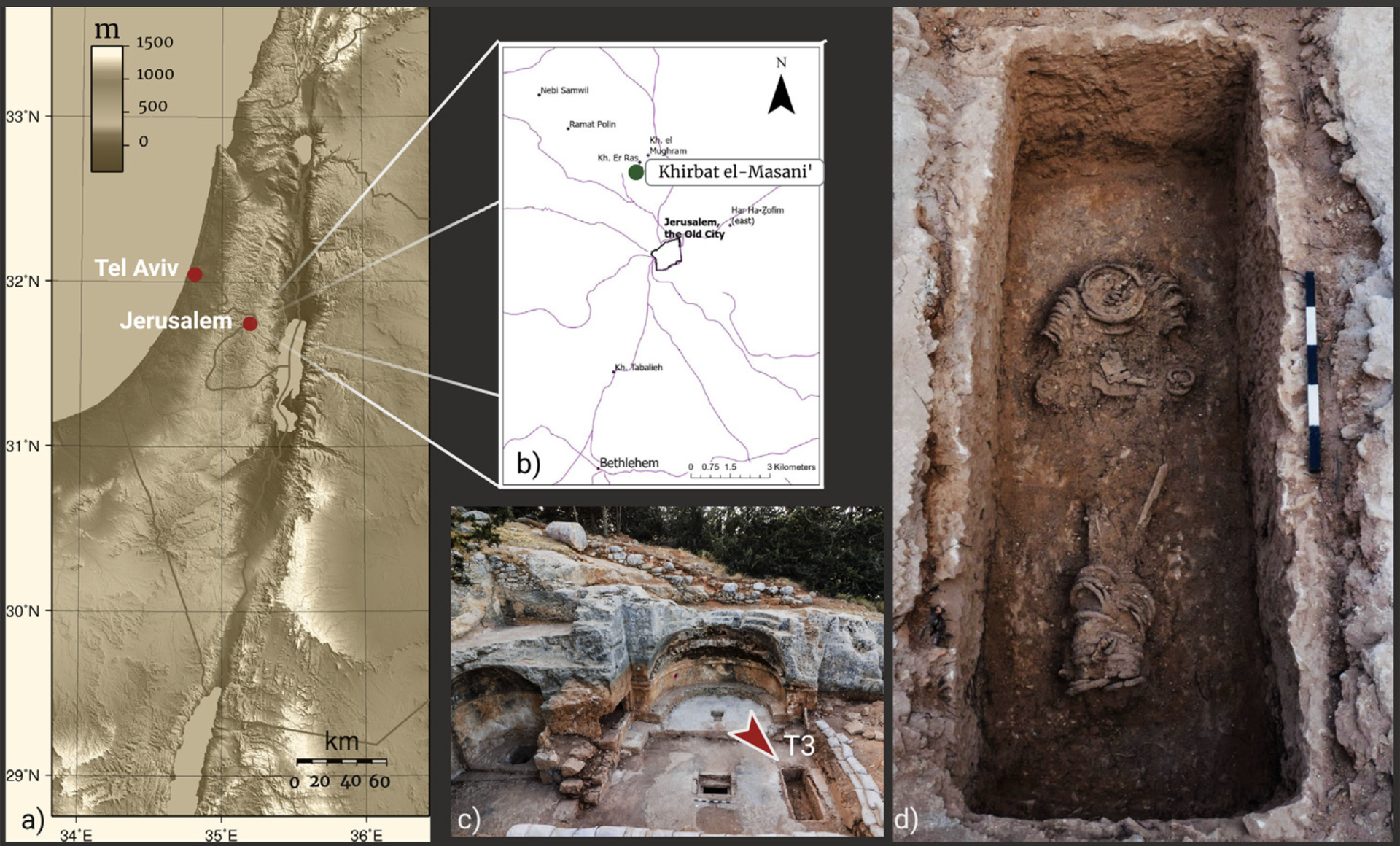

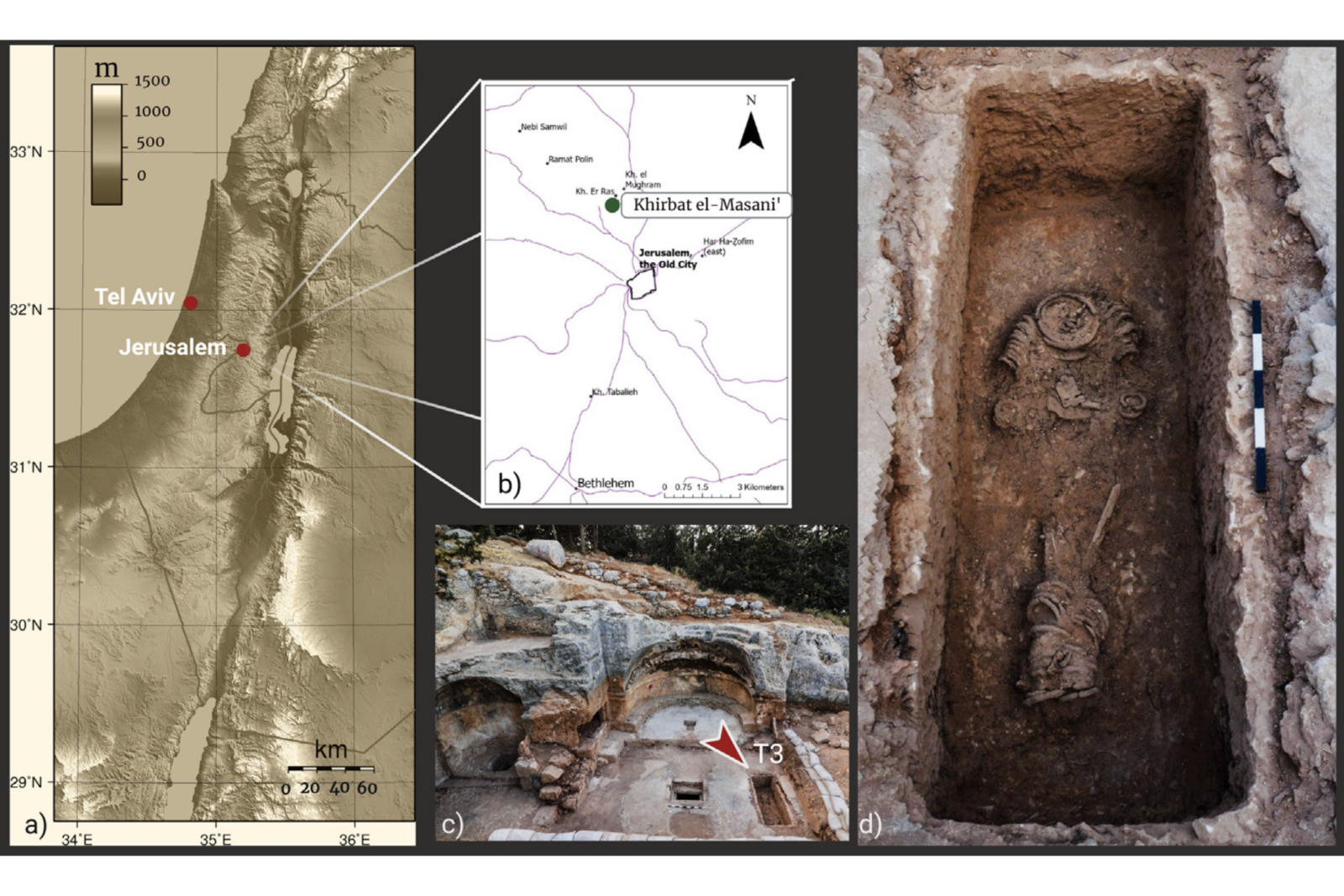

At the Byzantine-era monastery of Khirbat el-Masani, northwest of Jerusalem, researchers uncovered the remains of a 1,500-year-old ascetic wrapped in heavy metal chains.

Initially believed to be male—given the widely accepted assumption that extreme bodily mortification was a practice reserved for men—the skeleton was later confirmed to be female through advanced scientific analysis.

This discovery not only provides direct archaeological evidence of female participation in extreme ascetic practices but also forces historians to reconsider the role of women in Byzantine religious life.

The excavation, conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority in collaboration with the Weizmann Institute of Science, uncovered multiple burial crypts dating from the fourth to seventh centuries CE.

However, scientific analysis revealed an unexpected truth about early Christian times:

This revelation challenges assumptions about women's participation in extreme asceticism:

Implications of female skeleton discovery are significant to understand early Christian times:

Women in the Byzantine Empire were largely confined to domestic roles, with their participation in public and religious life heavily restricted.

Society viewed them as subordinate to men, and religious doctrine reinforced these norms by discouraging female leadership within the church.

While some women entered monastic life, their religious expression was generally believed to focus on prayer, charitable work, and self-denial rather than extreme bodily discipline.

However, historical records reveal that some women embraced asceticism, particularly among the aristocracy:

The discovery of the female skeleton Khirbat el-Masani challenges this perception by providing rare material evidence that some women engaged in severe ascetic practices traditionally associated with men. Until now, such practices were assumed to be exclusive to male monks.

By recognizing female ascetics who engaged in extreme bodily mortification, this discovery reshapes our understanding of gender roles in Byzantine religious life and calls for a reevaluation of women's spiritual contributions.

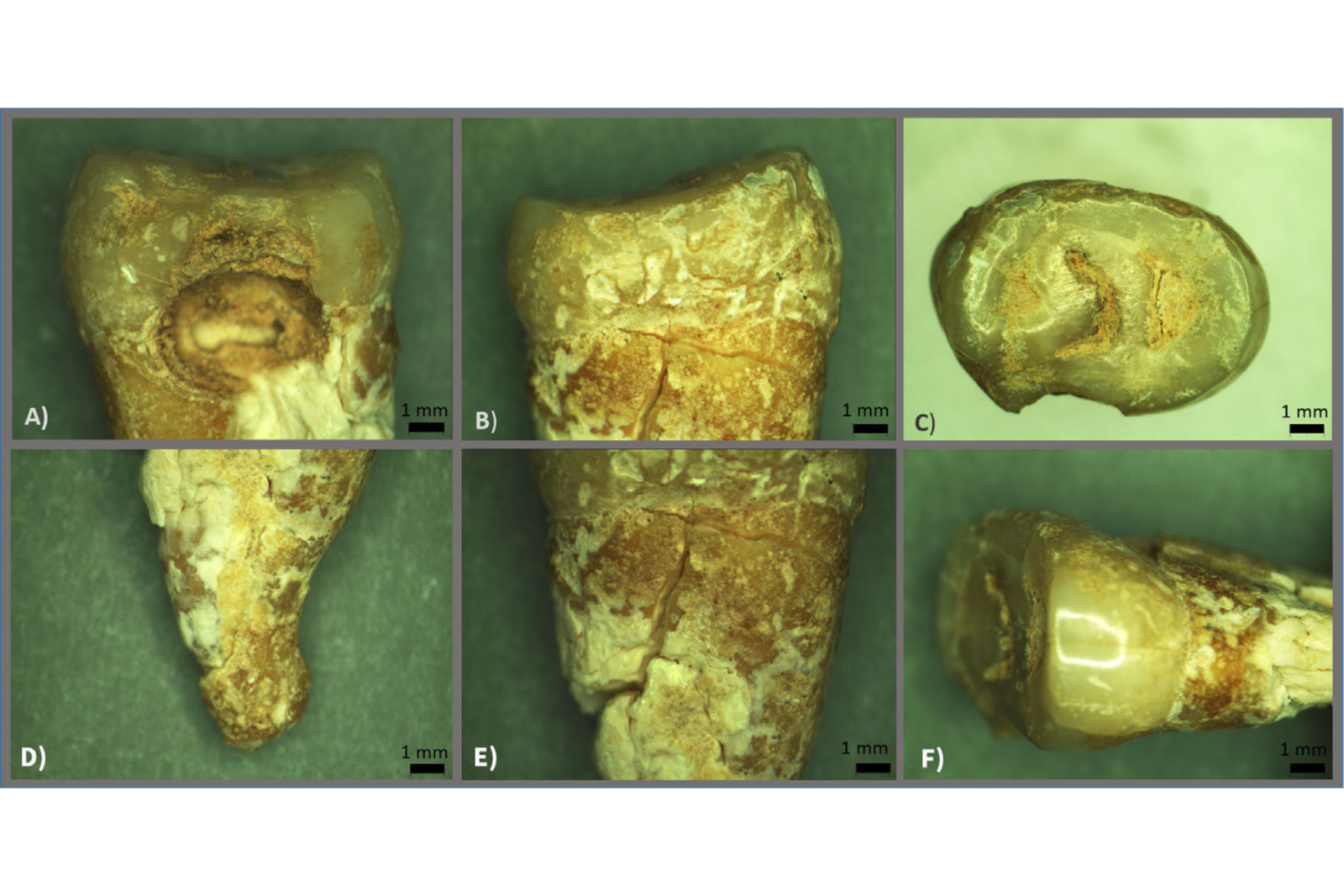

The sex determination of the remains was achieved through dental enamel proteomics, a method that extracts proteins from tooth enamel to determine biological sex. The poor condition of the skeleton made traditional osteological analysis insufficient, but this innovative approach conclusively confirmed the individual was female.

Dental enamel proteomics is a relatively recent but highly reliable technique, especially useful where skeletal remains are too deteriorated for traditional bone analysis. By analyzing peptides in tooth enamel—one of the hardest and most durable tissues in the human body—researchers can accurately determine biological sex, even in fragile archaeological remains.

Published in the "Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports", the study challenges long-standing assumptions about ascetic practices. Until now, physical evidence of female participation in extreme self-mortification was lacking.

The identification of this female ascetic has major implications for our understanding of Byzantine monasticism and religious history.

For centuries, male-dominated narratives have shaped how we view early Christianity, often overlooking or minimizing women's contributions. This discovery forces historians to rethink long-standing assumptions about who practiced extreme asceticism.

But this isn't just about one woman - it reflects a larger issue in archaeology: how assumptions shape historical interpretation.

This reminds me of a recent DNA study in Pompeii that overturned long-held beliefs about ancient family structures.

Just as modern biases shaped Pompeii's historical reconstructions, traditional gender roles have influenced how ascetic burials are interpreted.

The discovery of a female skeleton at Khirbat el-Masani, much like the Pompeii findings, shows the importance of scientific advancements in archaeology.

DNA and proteomic analysis can uncover truths that visual interpretation alone cannot, challenging long-held assumptions about the past.