The earliest form of the signature emerged not on paper but on clay. New analysis highlighted by Serdar Yalcin of Macalester College points to cylinder seals from ancient Mesopotamia as early instruments of authentication, identity and social status, offering a window into how early urban societies understood personal authority.

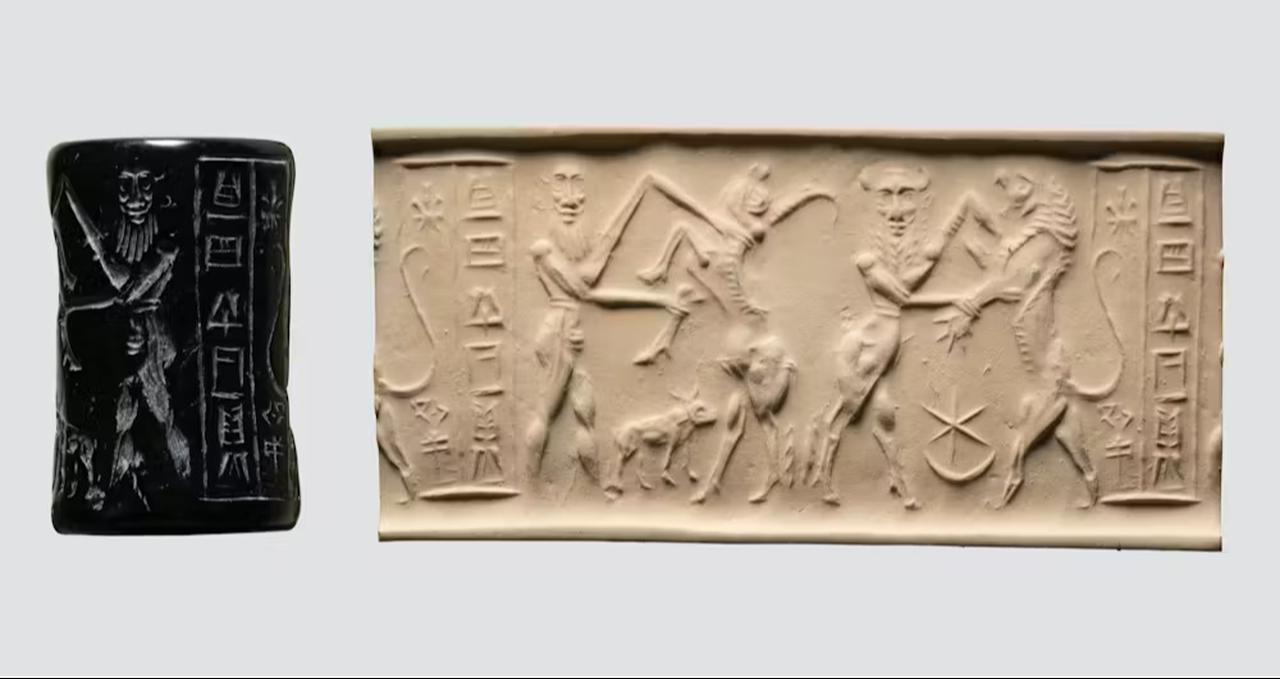

Cylinder seals were tiny carved stones, often no taller than a few centimeters, used to sign clay documents in the region between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. When rolled over moist clay, the images engraved in reverse on their surfaces left impressions that confirmed the owner had authorized the text. In that sense, the impressions served as the ancestor of both handwritten and digital signatures.

Thousands of these seals are now displayed in museums. Many were carved from precious stones such as lapis lazuli, agate or chalcedony, and reflect an artistic tradition that continued for millennia across what is now Iraq, Syria and neighboring regions.

Seals did not merely function as administrative tools. The choice of stone and the carving itself communicated identity. Communities in Mesopotamia rarely had direct access to valuable minerals, so stones were brought from distant lands: diorite from Oman, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and carnelian and agate from the Indus Valley. Because these materials were expensive, ownership of elaborately carved seals tended to indicate elite status.

Texts engraved on the seals often included the owner’s name, lineage, profession or place of origin. Some seals belonged to women, although in smaller numbers than to men. Religious identity also formed part of the imagery, with designs showing gods, worshippers or devotional inscriptions.

The imagery carved on seals developed into a broad visual language. Seal-cutters, artisans who specialized solely in this work, created scenes of ritual, daily life, mythological creatures and heroic stories. Some designs seem to have been made in advance and later customized, while others were carved specifically for officials associated with palace or temple administration.

In rare cases, rulers or royal aides oversaw the creation of seals to be gifted to high-ranking figures, which indicates that the objects also served diplomatic and political purposes. Losing a seal was seen as a deeply negative sign, because the object and its imagery were closely tied to the owner’s identity.

The use of seals emerged alongside developments often associated with the early state: writing, city life, organized religion and bureaucracy.

These structures shaped life in ancient Mesopotamia, and their modern equivalents—administrative records, social identity and formal signatures—continue to shape societies today.