In a groundbreaking experimental voyage, a team of researchers successfully recreated a Paleolithic ocean crossing using a hand-carved dugout canoe, shedding new light on one of humanity's earliest seafaring achievements. The project, conducted between Taiwan and Yonaguni Island in the Ryukyu archipelago, aimed to test the long-debated theory that Homo sapiens reached the remote Japanese islands as early as 35,000 years ago by sea.

The experiment revolved around the construction and open-sea deployment of a dugout canoe built with replicated Upper Paleolithic tools—primarily edge-ground stone axes. Measuring 7.5 meters in length, the canoe named Sugime was carved from a single Japanese cedar tree and modeled after early Holocene designs. Despite the absence of physical evidence for Paleolithic boats in the region, the use of similar tools in both Japan and Australia suggests such vessels could have been produced during that time.

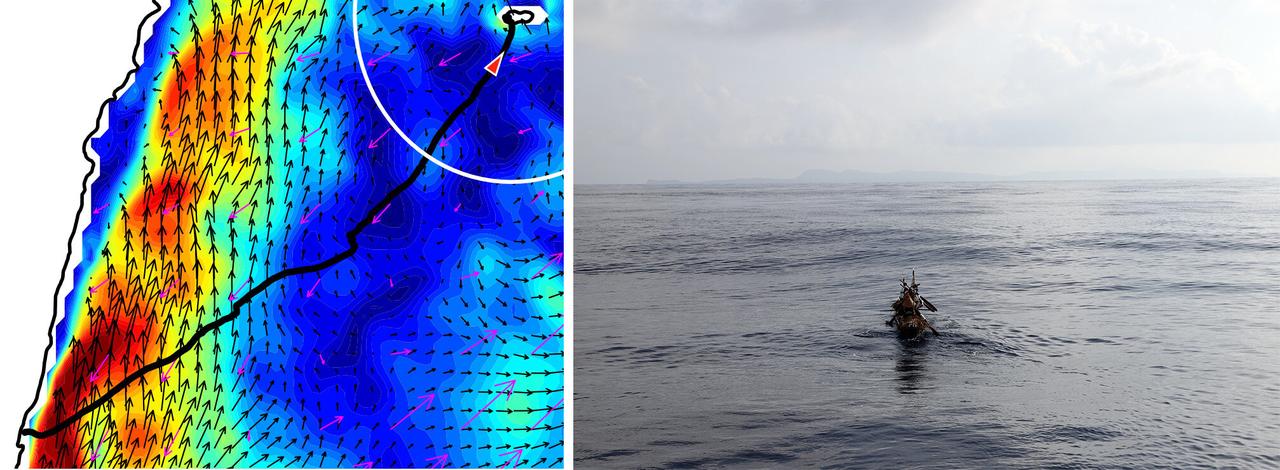

The central challenge was crossing the 110-kilometer strait separating Taiwan and Yonaguni Island, an area dominated by the powerful Kuroshio Current. Flowing northward at speeds reaching up to 2 meters per second, this current is among the world's strongest and would have posed a formidable barrier for early seafarers.

On July 7, 2019, five skilled paddlers—four men and one woman—set out from Wushibi, a coastal site in eastern Taiwan. Relying solely on natural cues such as stars, swells, and wind patterns, the team navigated east-southeast for the first 24 hours, then veered northeast, mirroring a route that ancient travelers might have followed.

The canoe was forced to contend with changing weather, strong ocean swells, and physical exhaustion. The paddlers, unaided by modern navigation tools, reported hallucinations, gastrointestinal cramps, and sleep deprivation. Yet they pressed on, driven by teamwork and guidance from an experienced captain.

After drifting briefly due to overcast skies and uncertainty during the second night, the crew finally spotted the silhouette of Yonaguni Island at dawn on the third day. The canoe landed at Nama Beach after 45 hours and 10 minutes at sea, having covered a total distance of 225 kilometers.

This success followed earlier failed attempts using bamboo and reed rafts, which could not overcome the force of the Kuroshio. The dugout's superior speed and durability, despite its instability and the need for constant water bailing, demonstrated its potential as a viable Paleolithic seafaring vessel.

The voyage also highlighted the importance of human factors such as paddling skill, leadership, and group cohesion—elements often overlooked in archaeological studies that focus primarily on artifacts.

Although the experimental canoe was aided by safety escort ships and its paddlers had some modern geographical knowledge, the voyage offers credible support for the idea that early humans possessed the technical and cognitive capabilities to cross vast ocean barriers.

The results suggest that dugout canoes were likely used in the first full-scale maritime migrations in the Western Pacific. With evidence of edge-ground stone tools dating back 38,000 years in Japan, and sea crossings to other Japanese islands dating to similar periods, researchers argue that maritime migration to the Ryukyus was part of a broader expansion pattern by anatomically modern humans.