The widely shared story that Japan owes part of its robotics know-how to an Ottoman automaton allegedly gifted by Sultan Abdulhamid II does not hold up to scrutiny.

There is no archival record that a human-sized device called “Alamet”—described as a whirling dervish figure that would walk, turn, and recite the adhan (the Muslim call to prayer) on the hour—was built in Istanbul and shipped to Tokyo.

A leading historian has underlined that Ottoman archives contain no such document, and materials used to prop up the tale trace back to unrelated early-20th-century automata and a fictional account published online in 2009.

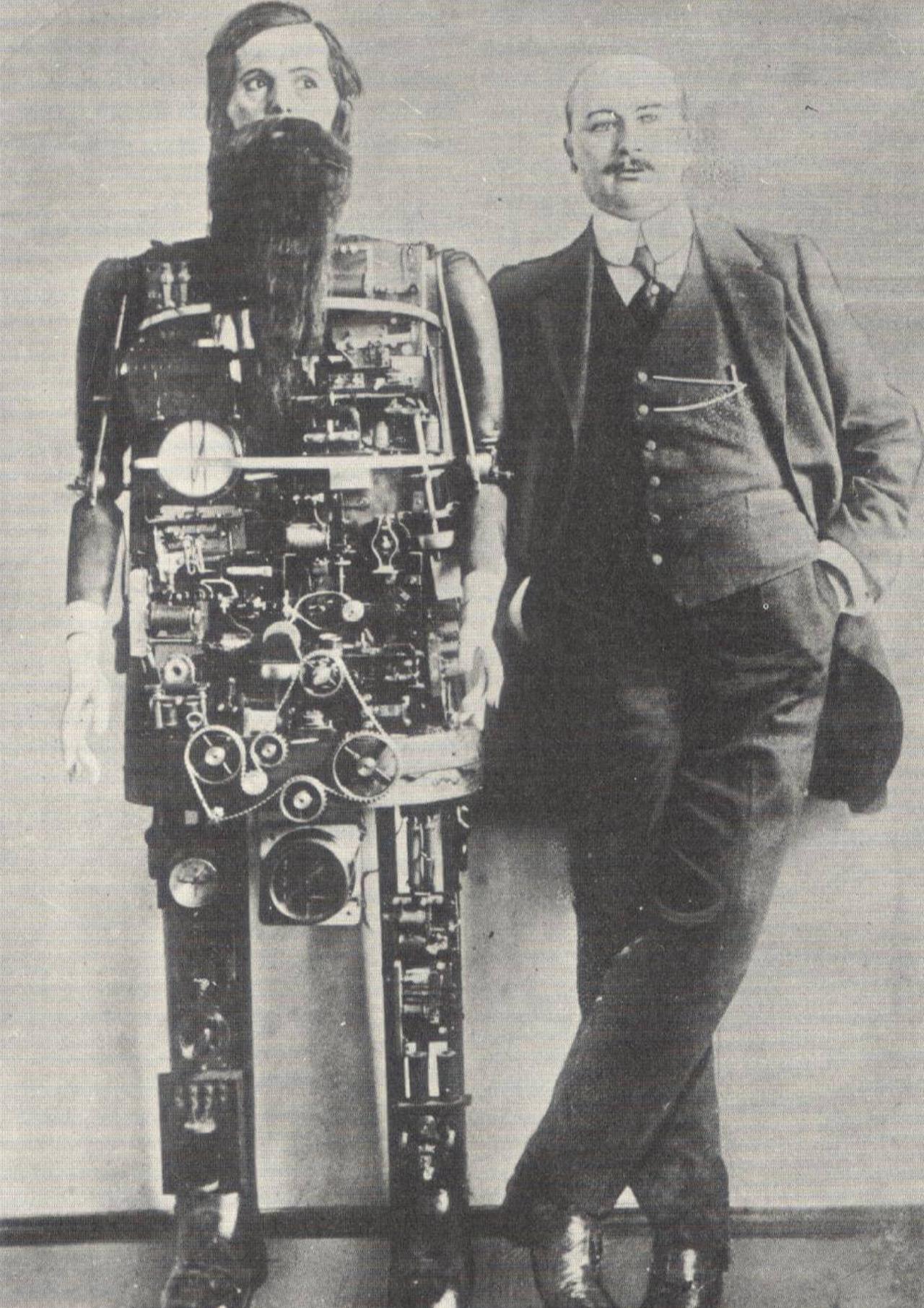

Images that were repeatedly shared as “proof” of Alamet actually line up with “Occultus” (also known as “Barbarossa”), a robot attributed to German inventor Adolph Whitman and unveiled to the public in 1909.

Contemporary publications covered the exhibit, and later discussions even argued the machine was a stage piece rather than a functioning robot.

These pictures do not show an Ottoman-made device, and they do not connect to a gift from the sultan to Japan.

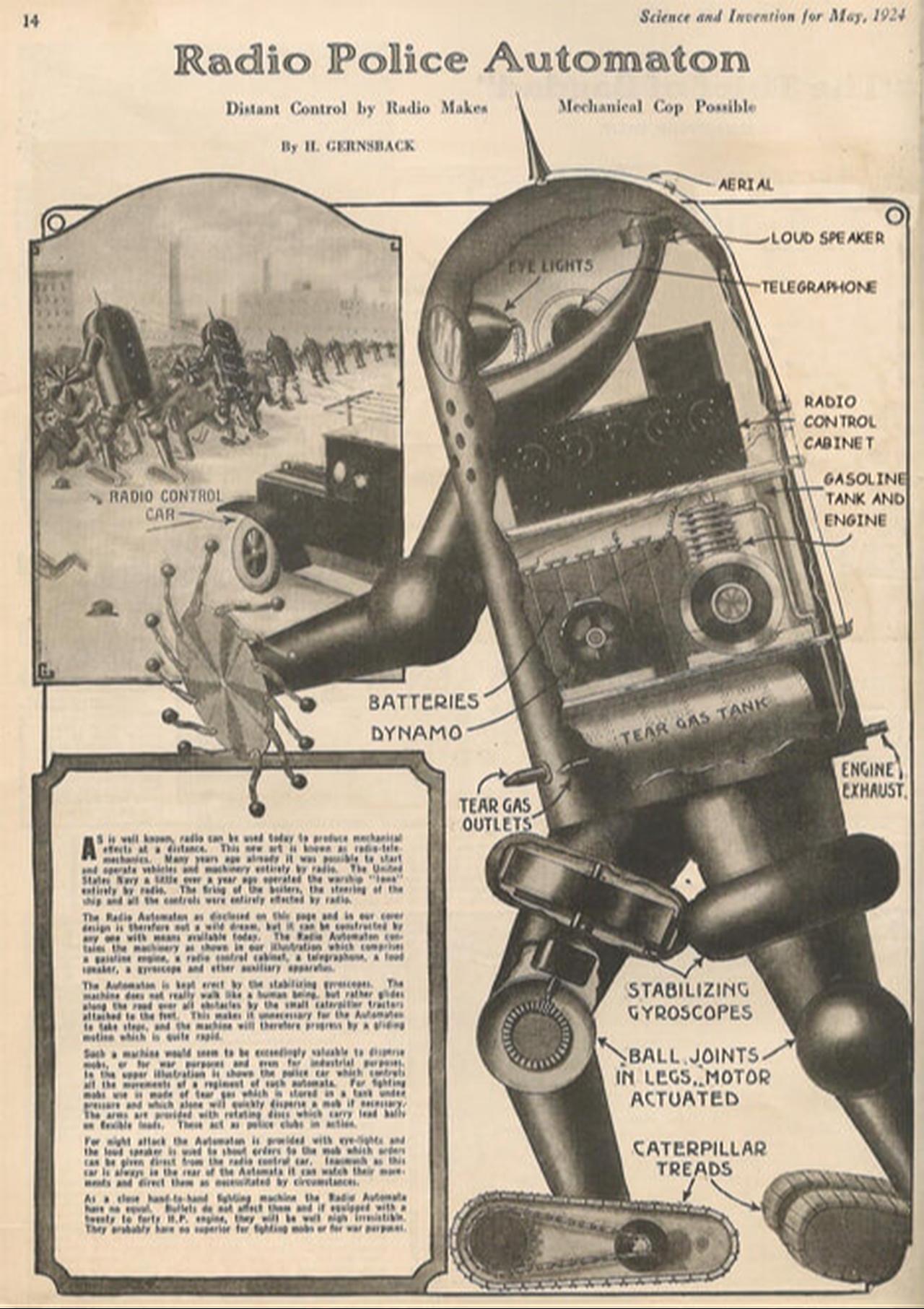

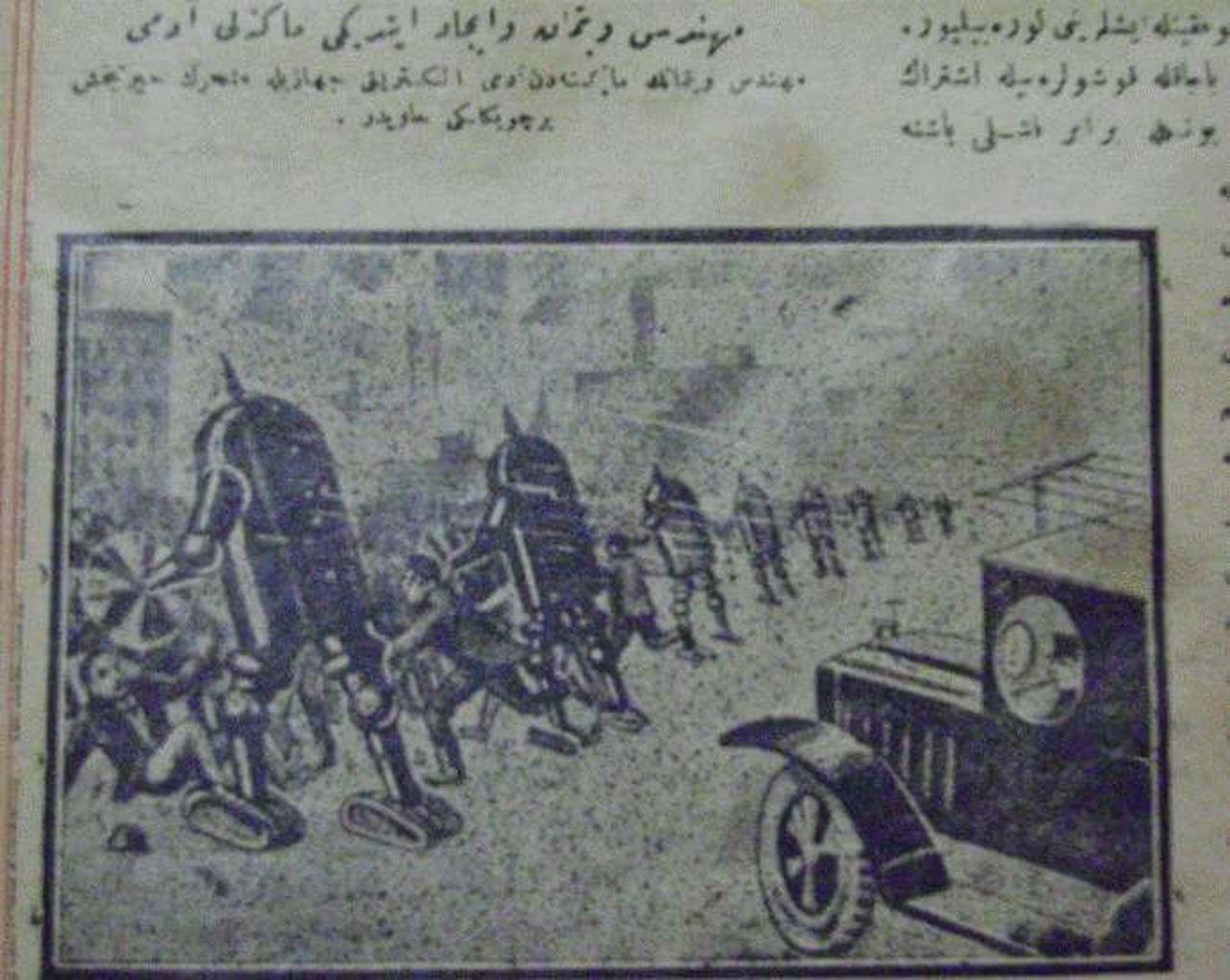

Another image often attached to the claim shows the so-called “radio police automaton,” better known as Gernsback’s Robot Soldier, which appeared in the May 1924 issue of Science and Invention.

Although the illustration has been circulated alongside the Alamet story, it depicts a different, speculative concept and does not mention Sultan Abdulhamid II or any Ottoman linkage.

Versions of the story say Sultan Abdulhamid II sent the robot with a letter and decorations aboard the Ertugrul frigate, which indeed sank on its return voyage with 450 crew.

However, researchers note there is no recorded vesika (official document) that an automaton left the Ottoman court for the Japanese emperor.

In this telling, semazen refers to a whirling dervish performer in the Mevlevi Sufi tradition, a figure said to have inspired the robot’s design—a detail that appears only in later narratives, not in official files.

Writers have traced the viral storyline to “Sultan Abdulhamid II and Robot Technology,” an online piece from June 4, 2009, which expanded a plot he framed as historical fiction.

A 2016 article in Aydinlik reported that the tale leaned on a fabricated Ottoman-era newspaper page combining unrelated robot images; the same report linked the narrative’s spread to coverage that treated the fiction as fact.

A court filing by attorney Abdullah Egeli further stated that the story was adapted into a screenplay without permission, naming production companies and a producer, and even citing a website presenting the plot as a film project.

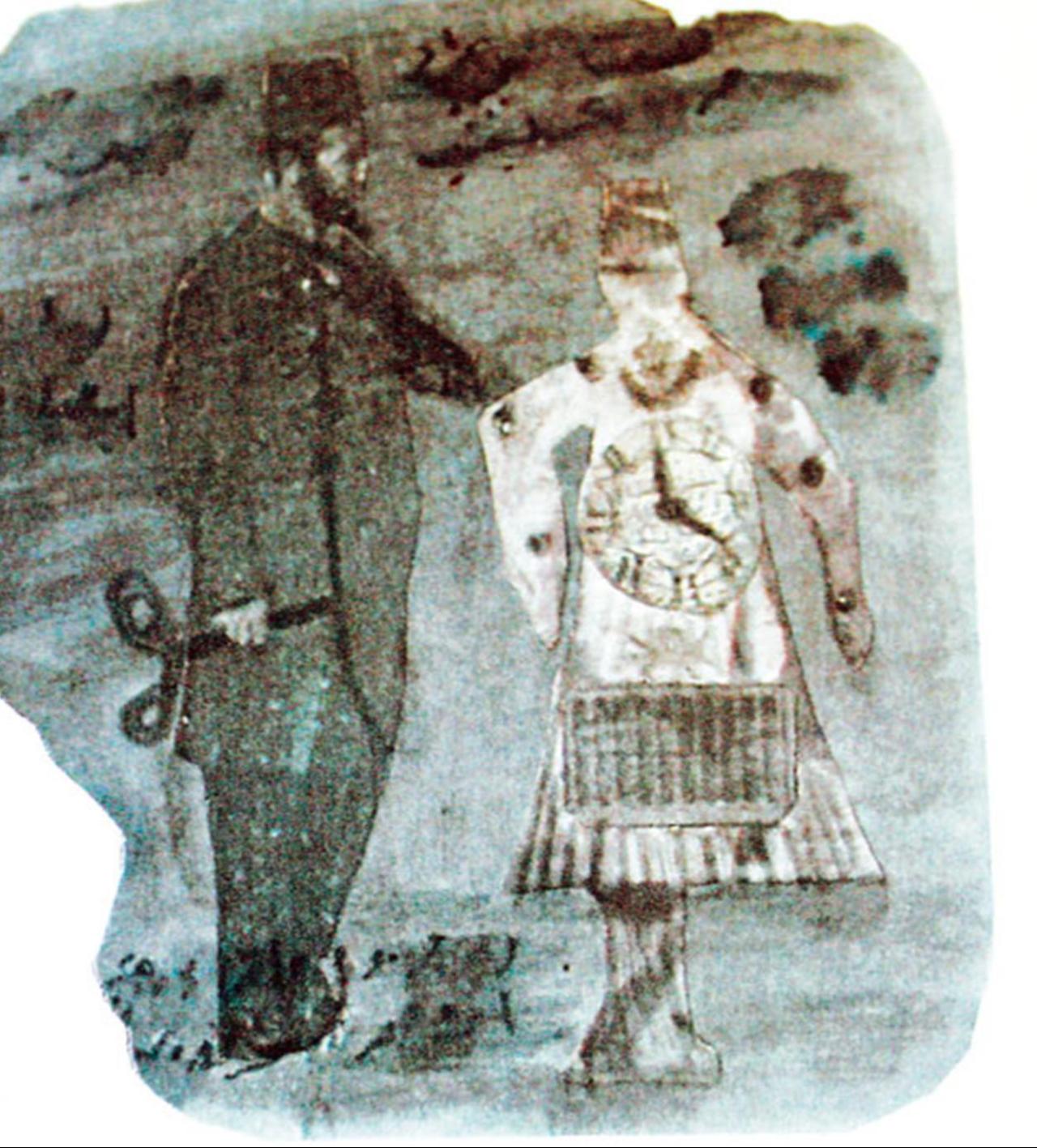

One oft-reposted photo shows a supposed semazen-shaped robot beside an attendant with a winding key, sometimes tied to a claim that original images were damaged in the Yildiz Palace fire (Yildiz being the late Ottoman imperial complex in Istanbul).

The source of this specific photograph has not been identified, and it does not establish that an Ottoman robot named Alamet ever existed.

Proponents have said the sultan ordered a “technology marvel” that opened its arms, spun, spread silver skirts, walked half a meter, recited the adhan, and then returned to its place, allegedly inspiring Japanese robotics.

Yet the photos point elsewhere, the magazine illustration belongs to a different story, the semazen image lacks provenance, and archival checks have not turned up any document that such a robot was made or sent. As a result, the narrative remains unsupported by evidence.