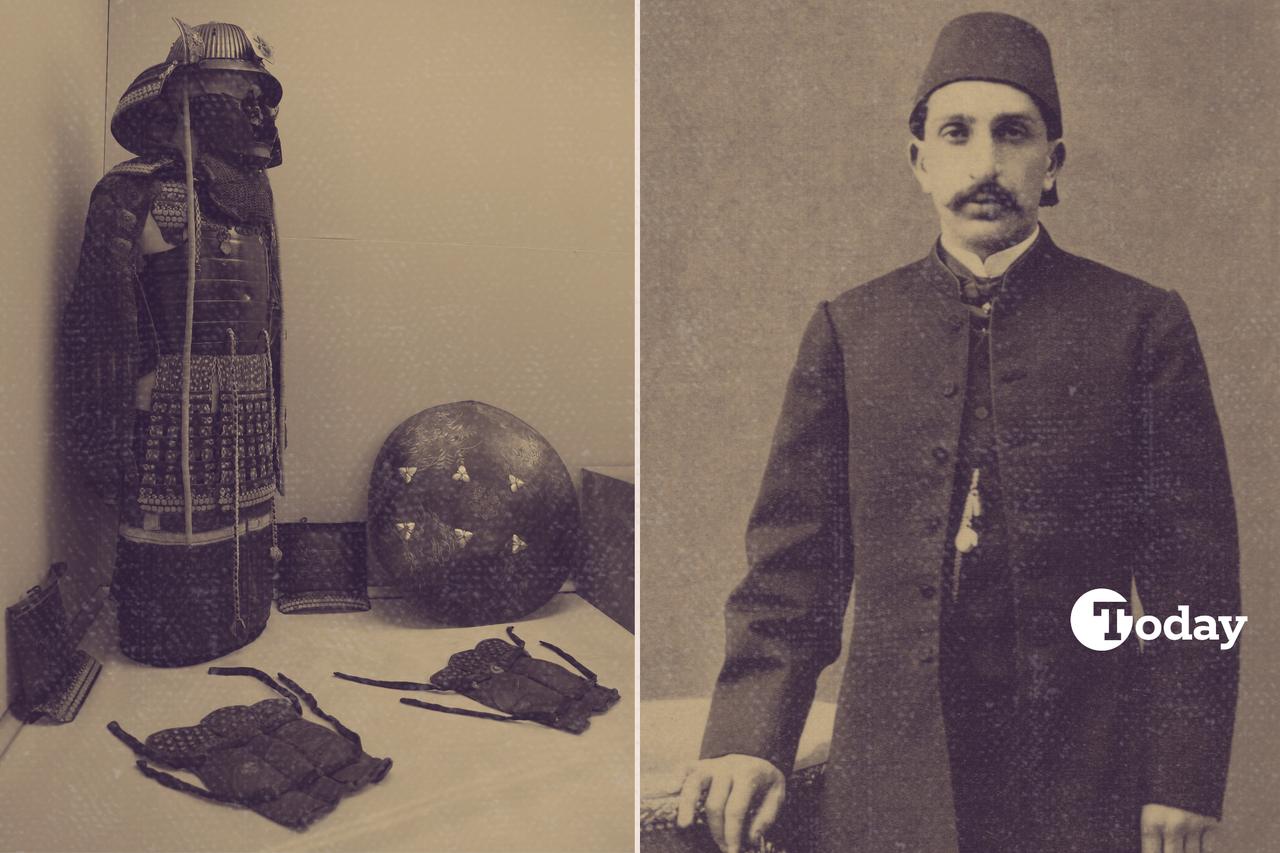

A suit of Japanese samurai armor presented to Sultan Abdulhamid II is now on display at the Palace Collections Museum in Istanbul’s Besiktas district, standing as a tangible marker of how Ottoman–Japanese relations took shape in the late 19th century and strengthened further in the wake of what sources describe as the worst maritime disaster in the country’s history.

Ottoman diplomacy long leaned on formal gift exchange to warm up relations, and distant powers followed suit to keep channels open.

An ivory oil lamp sent from Japan to Sultan Abdulaziz in 1873 kicked off a friendship that would carry on for decades, with both sides using carefully chosen presents to signal respect and intent.

During the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1868), Japan largely shut its ports to foreign states, except for limited ties with China and the Netherlands. In the 1850s, the country signed new trade agreements but, as Japanese officials saw it, those texts did not grant equal rights. After 1868, the new government made customs and foreign relations a priority.

By 1871, officials sent Fukuchi Genichiro to assess the Ottoman Empire, and in 1875, senior figures argued that Turks, as a non-Christian Western nation dealing diplomatically with Europe, looked similar to Japan and could offer useful lessons.

In January 1881, Yoshida Masaharu, serving as a foreign ministry adviser, visited Istanbul and met Sultan Abdulhamid II.

The sultan said a formal friendship treaty would be necessary, yet no immediate result came out of those talks. Even so, the visit helped lay the groundwork for more visible exchanges.

In 1887, Prince Komatsu Akihito and his wife stopped in Istanbul during a European tour and met the sultan at Yildiz Palace. The palace assigned Goksu Kasri for the delegation’s use throughout the visit, and the sultan awarded the couple the Ottoman “Imtiyaz Nisani,” an order of distinction granted for merit and service.

Afterward, Emperor Meiji sent further gifts, including the highest Japanese decoration, the Chrysanthemum Order—an honor reserved for members of the imperial family, reigning monarchs and heads of state.

Sources note that backplates associated with the gift bear the phrases, “The flag brings victory to the army” and “The flag increases the glory of the army.”

The museum is exhibiting a suit of Japanese body armor for the first time, along with a small model of a Japanese temple included among the presents. The armor carries the fine details of traditional Japanese art. Accounts differ on who physically handed the armor over to the Ottoman court: while one strand credits Emperor Meiji, another points to the businessman Torajiro Yamada.

The uncertainty most likely stems from the long, later looting of Yildiz Palace after Abdulhamid II was deposed, when official gifts and collected objects were removed, dispersed and, in some cases, only much later granted to museums by private holders.

Museum director Guller Karahuseyin states that the armor dates back to the 1600s and belonged to samurai warriors. “This armor includes a shield, a sword and a flag and is said to have been used in combat. There is also a dent on it that must have occurred during a battle,” she says.

According to the museum, the armor reached the Ottoman court and was presented to Sultan Abdulhamid II in 1892. The exhibit also features the Chrysanthemum Order insignia sent after the 1887 visit and the model of a Japanese shrine gifted for the 25th anniversary of the sultan’s enthronement.

The artifacts are currently on view at the Palace Collections Museum in Besiktas. The museum opens daily from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., except on Mondays.