An academic study by Serdar Ozbilen of Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University has unveiled a startling historical lineage that connects the brutal decapitation practices of ancient Mesopotamia and Anatolia to the terrorist tactics seen in the last few decades. Drawing on archaeological evidence, historical records, and iconography, the study paints a vivid and disturbing picture of how the symbolic meaning of the severed head has transcended millennia.

This research tracks the use of beheading—from early Neolithic societies to the imperial propaganda of the Neo-Assyrians—and reveals its transformation into an enduring cultural motif. The practice was never merely an act of violence; it was deeply ritualistic, political, and communicative.

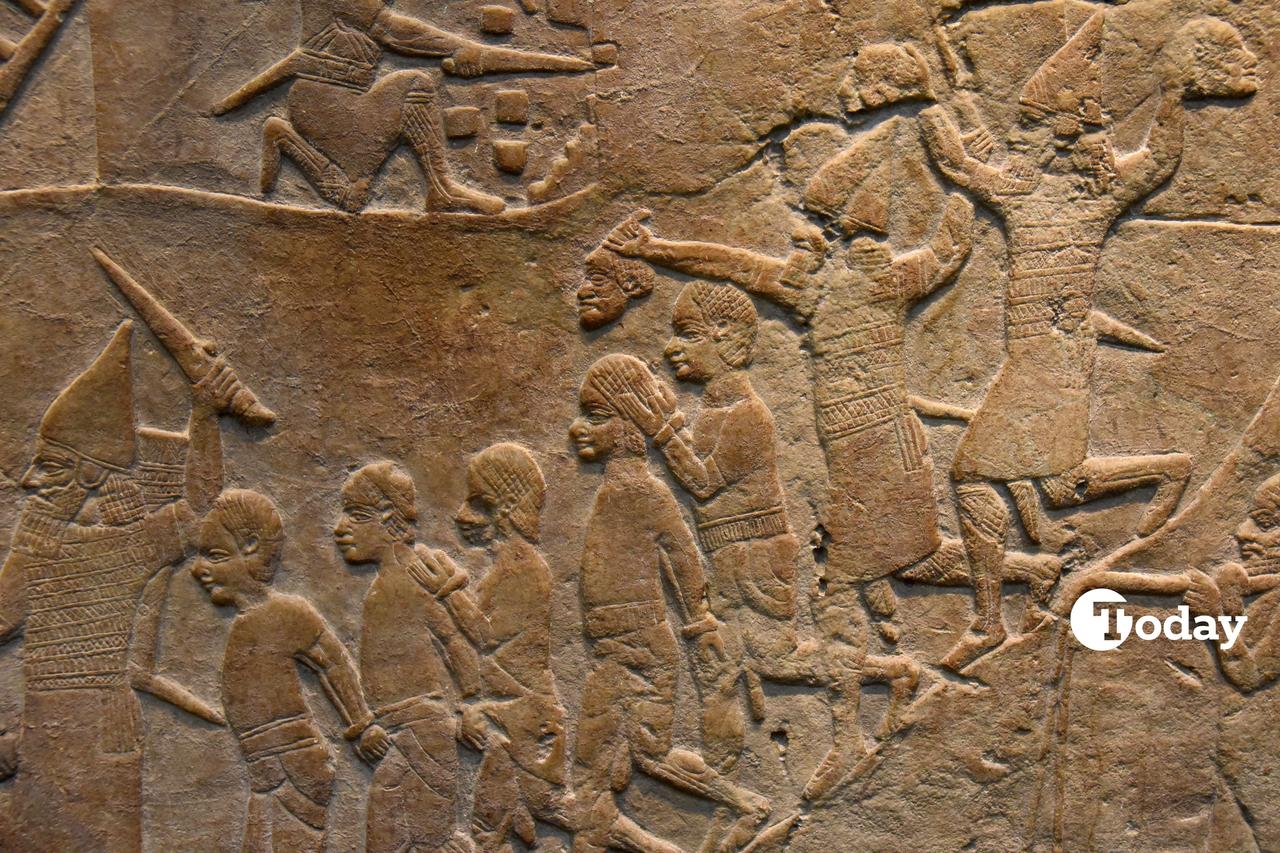

Decapitation in the Ancient Near East was more than execution—it was theatre. In empires such as Neo-Assyria, kings not only killed their enemies but also displayed their heads publicly, often on city walls or on the bodies of enslaved allies. These heads became tools of psychological warfare. The visual impact of a severed head was magnified by the symbolism embedded in it—identity, honor, and power were literally removed from the body and placed on display.

One of the most striking examples comes from the reign of Ashurbanipal (seventh century B.C.), who paraded the severed head of Elamite King Teumman through the streets of Nineveh. In this act, the head became a trophy, a warning, and a divine reaffirmation of legitimacy all at once.

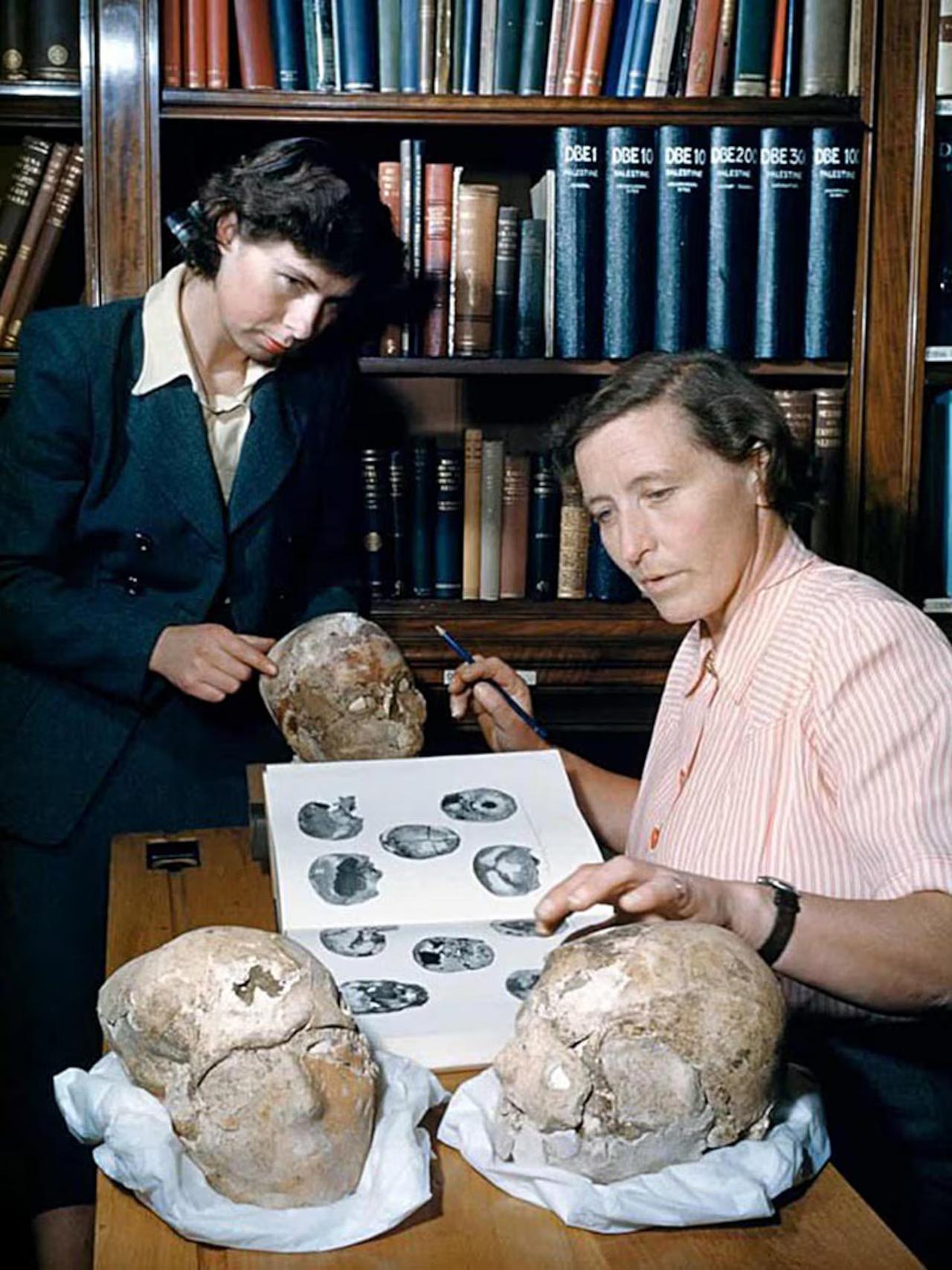

Long before empires rose, early societies in what is now Türkiye engaged in skull cults. At sites such as Catalhoyuk and Gobeklitepe, archaeologists found evidence of secondary burial practices and skull modification. These headless burials were often adorned with vultures in wall paintings—a possible symbol of spiritual ascent or cosmic justice.

While interpretations vary, some scholars suggest that these displays may have functioned as memorials to fallen enemies or revered ancestors. Ozbilen's study notes a compelling hypothesis: that the removal and curation of skulls signified both reverence and domination, a duality that echoes in the use of heads in later Mesopotamian warfare.

What relevance do these ancient rituals have today? More than might be comfortable to admit.

Extremist terrorist groups, especially in the Middle East, have exploited the symbolic weight of beheading, broadcasting decapitations in high definition as part of their psychological campaigns. While the context is different, the function remains chillingly similar: display, dominance and deterrence.

These acts revive an ancient vocabulary of fear. The severed head, still, sends a message. And as Ozbilen points out, its impact is heightened by a cultural subconscious that recognizes the motif, even if not consciously.

One alternative form of beheading rituals involved targeting the heads of statues belonging to another civilization during an attack. For example, when the Assyrian soldiers looted the temple of the god Haldi in Musasir under Sargon II, they damaged a statue—an act that can be compared today to the destruction of statues in Middle Eastern museums by terrorists.

The study argues that understanding the roots of these practices is essential to deconstructing their current manifestations. Beheading is not only a method of execution but a carefully curated spectacle. Whether in a Neo-Assyrian relief or a terrorist propaganda video, the head is a message.

What this research underscores is a haunting continuity. From prehistoric Anatolian burials to medieval royal executions, from Roman martyrdoms to modern Middle Eastern conflicts, the symbolic decapitation of the human form persists as a powerful tool of narrative and domination.