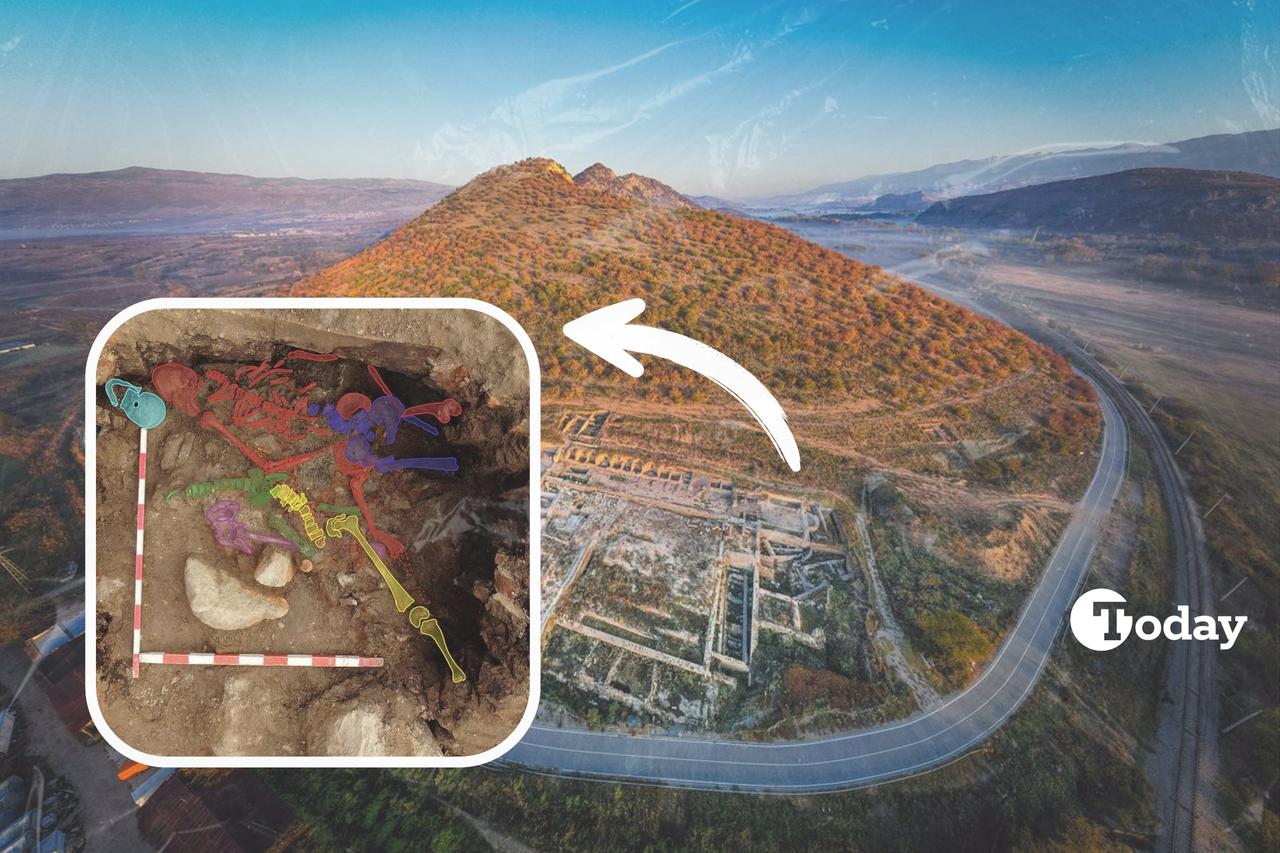

Archaeologists working in the Roman city of Heraclea Sintica in southwestern Bulgaria have uncovered the skeletal remains of six people who perished when a massive earthquake struck the region at the end of the fourth century A.D.

The discovery was made in the southwestern corner of the city’s Roman forum, where excavations revealed two brick-vaulted water cisterns. One of them had collapsed during the disaster, burying those who sought shelter nearby. The remains, sealed beneath rubble and groundwater sediment for over 1,600 years, provide a rare glimpse into both the final moments and the health conditions of the city’s inhabitants.

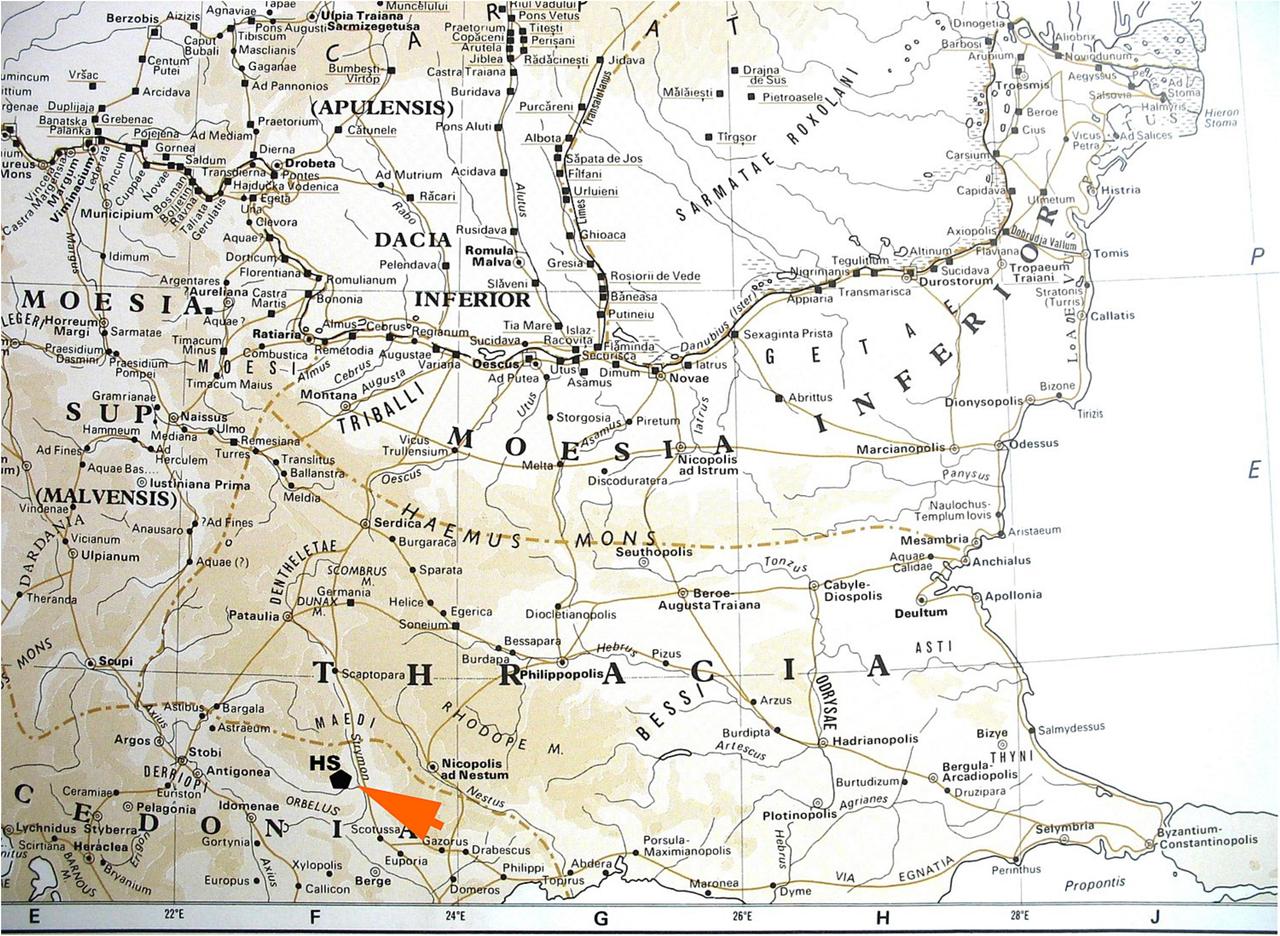

Heraclea Sintica developed as a thriving settlement under Roman rule thanks to its strategic location between the Struma River and the Kozhuh uplands. By the fourth century, the city featured an elaborate forum, temples, and public buildings. But this prosperity was violently interrupted by a series of seismic events known in scholarship as the “earthquake storm” that ravaged the Eastern Mediterranean between the fourth and sixth centuries A.D.

One of the most devastating of these, the quake of July 21, 365 A.D., caused widespread destruction across the region, and Heraclea Sintica was among the cities affected. The newly studied remains mark the first confirmed earthquake casualties identified in this Roman town.

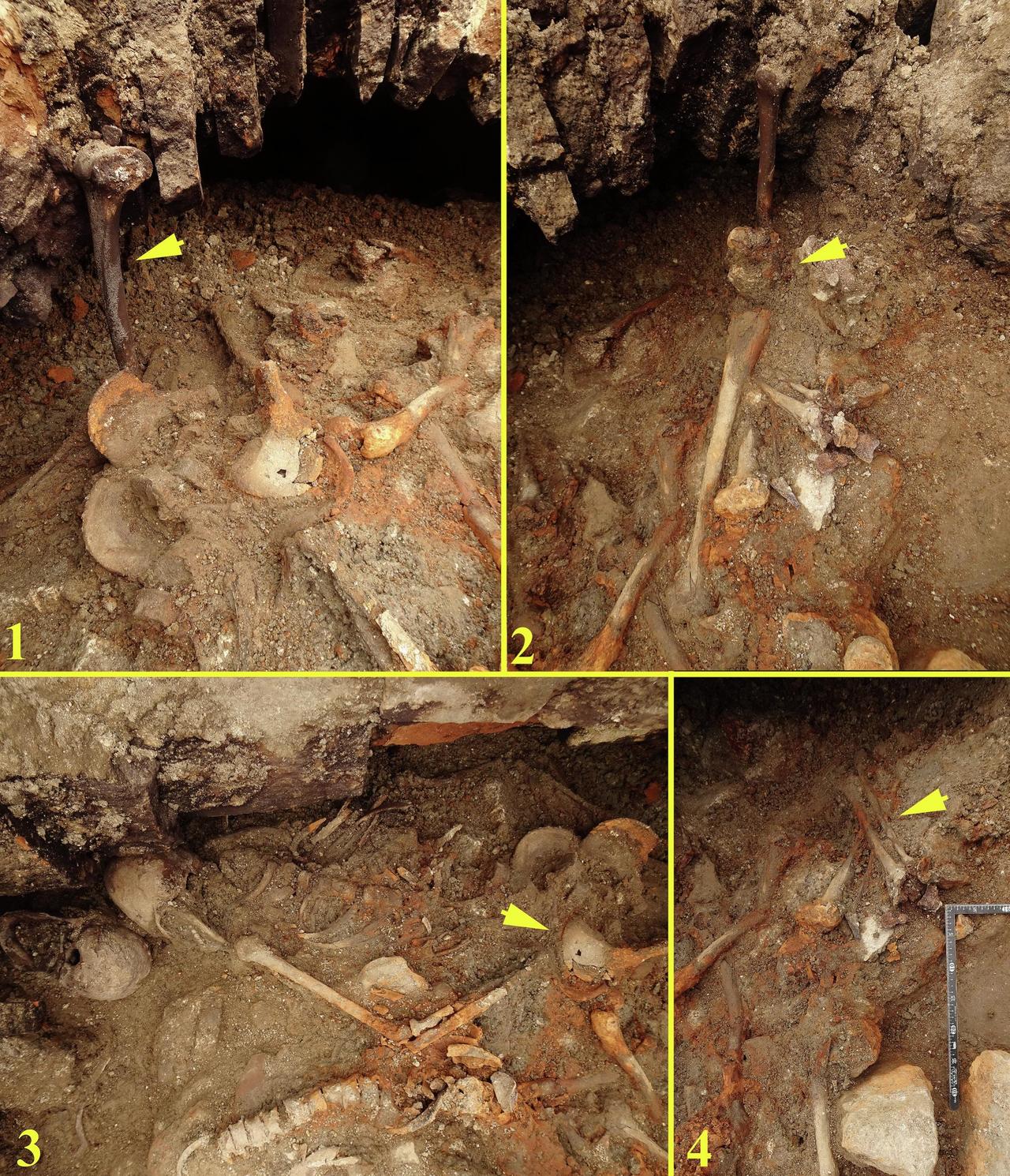

Archaeologists found five skeletons preserved in partial anatomical position on top of the collapsed vault. A sixth body was located at a higher level, suggesting that this person may have been standing on an upper structure or perhaps trying to help others during the tremors.

The way the skeletons were layered indicates that the individuals fell together into the cistern as the vault gave way. The preserved trauma, including skull fractures and broken ribs, suggests death was caused by both the fall from a height of around six meters and the heavy masonry that rained down upon them.

Among the victims, one young man aged between 18 and 25 displayed striking congenital pathologies. His skull revealed signs of a cleft palate, abnormal cranial growth (known as craniosynostosis), and missing teeth. These features strongly suggest Apert syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that would have caused severe physical and possibly cognitive impairments.

Despite these challenges, this individual lived into early adulthood, implying that he received long-term care within his community. Another skull found in the same deposit bore similar signs of cleft palate, hinting at a possible family relationship. Scholars note that such cases shed light on how ancient societies treated people with disabilities, suggesting that even those with visible impairments could find a place in Roman provincial life.

No personal belongings such as jewelry, coins, or clothing were found with the bodies, leaving their social status unclear. Researchers suggest that most residents of Heraclea Sintica likely escaped the earthquake or were recovered and properly buried afterwards. These six individuals, however, remained hidden beneath the collapsed cistern when the area was later leveled but never rebuilt.

Life in the city continued for a time on a smaller scale, but another earthquake in the fifth century led to its permanent abandonment. The tragic remains of these six people thus stand as a frozen moment in the city’s history, offering rare evidence of everyday lives suddenly cut short by natural catastrophe.