A team of scientists has discovered a new species of crocodile dating back to the age of dinosaurs in Egypt’s Western Desert that survived mass extinction, according to a statement released by Mansoura University.

The discovery revealed a crocodile that lived in Egypt about 80 million years ago. Details of it were published in The Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, a scientific journal devoted to zoology and specializing in evolutionary biology.

Sherif Khater, president of Mansoura University, expressed his pride in this new achievement, which adds to the university’s growing record of scientific accomplishments.

He said this success represents a true reflection of the university’s vision to support applied scientific research that serves humanity and strengthens its position among leading universities worldwide.

This giant crocodile lived about 80 million years ago in what is now Egypt’s New Valley Governorate. Scientists have named it Wadisuchus kassabi, making it one of the most significant discoveries shedding light on life in prehistoric times.

Wadisuchus represents the oldest known member of the Dyrosauridae family—a group of marine crocodiles that survived the mass extinction of the dinosaurs and thrived afterward—making it a rare witness to a pivotal stage in the evolution of ancient reptiles.

Unlike today’s crocodiles, which inhabit rivers and swamps, this ancient species lived along coasts and in shallow seas.

It was highly adapted to hunting in open waters, thanks to its long snout and sharp teeth, which made it an efficient predator capable of surviving after the dinosaurs’ disappearance.

The name Wadisuchus kassabi reflects strong Egyptian roots. “Wadi” refers to the discovery site in the New Valley, while “suchus” comes from Sobek, the ancient Egyptian crocodile god, and “kassabi” honors the late geologist Ahmed Kassab.

Sara Saber, an assistant lecturer at Assiut University and lead author of the study, explained that the findings offer new insight into how reptiles adapted to marine environments after major extinction events.

She added that the crocodile measured between 3.5 and 4 meters long, with a very elongated snout and sharp teeth, making it a specialized fish hunter.

Wadisuchus differs from its relatives by having four front teeth instead of five, nostrils positioned higher on the snout for breathing at the water’s surface, and a deep cavity where the jaws meet.

The researchers emphasized Africa’s pivotal role—particularly Egypt’s Western Desert—in the origin and evolution of this group of marine crocodiles.

They noted that the discovery highlights the vast scientific treasures still hidden beneath the sands of Egypt’s Western Desert.

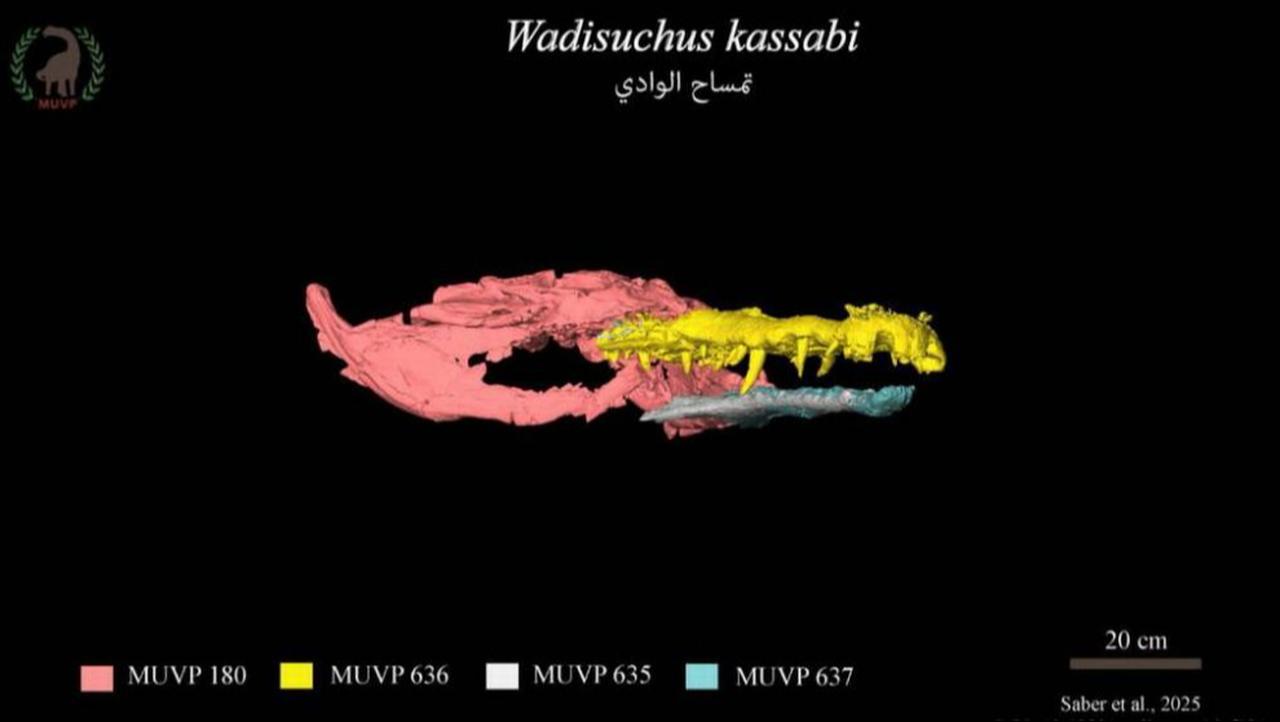

Hesham Sallam, head of the Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology Center (MUVP), explained that the crocodile’s remains were found in the Kharga and Paris oases.

The discovery includes parts of skulls and snouts belonging to several individuals of different ages, offering scientists a unique opportunity to study the evolutionary development of this ancient crocodile species.

Sallam noted that the research team used 3D CT scanning technology, which allowed them to uncover previously unseen anatomical details, providing a clearer picture of the internal structure of these ancient marine creatures that once roamed Egypt’s coasts.