In the summer of 1831, an ambitious Scottish-American shipbuilder named Henry Eckford sailed into the Golden Horn aboard a powerful 26-gun corvette, carrying with him the seeds of a revolutionary partnership that would transform Ottoman naval power and establish the first significant technological cooperation between the United States and Türkiye. This forgotten chapter of American-Ottoman relations reveals how, nearly two centuries before today's F-16 deals and defense partnerships, American naval expertise played a pivotal role in modernizing one of the world's great empires.

The story begins with catastrophe. On October 20, 1827, the combined British, French, and Russian fleets destroyed the Ottoman-Egyptian navy at the Battle of Navarino, sinking or capturing nearly 60 vessels and effectively ending Ottoman naval supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. For Sultan Mahmud II, known as the "Peter the Great of Türkiye" for his sweeping reforms, the humiliation demanded immediate action. But rather than turning to traditional European allies, the Sultan looked west—to the emerging American republic that had proven its naval prowess in the War of 1812 against the British.

The foundation for this unprecedented cooperation was laid in the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation signed between the United States and Ottoman Empire on May 7, 1830. While the public articles focused on trade relationships, a secret ninth article contained something far more significant: an agreement for the United States to build and sell warships to the Ottoman Empire without profit, essentially providing military assistance disguised as commerce.

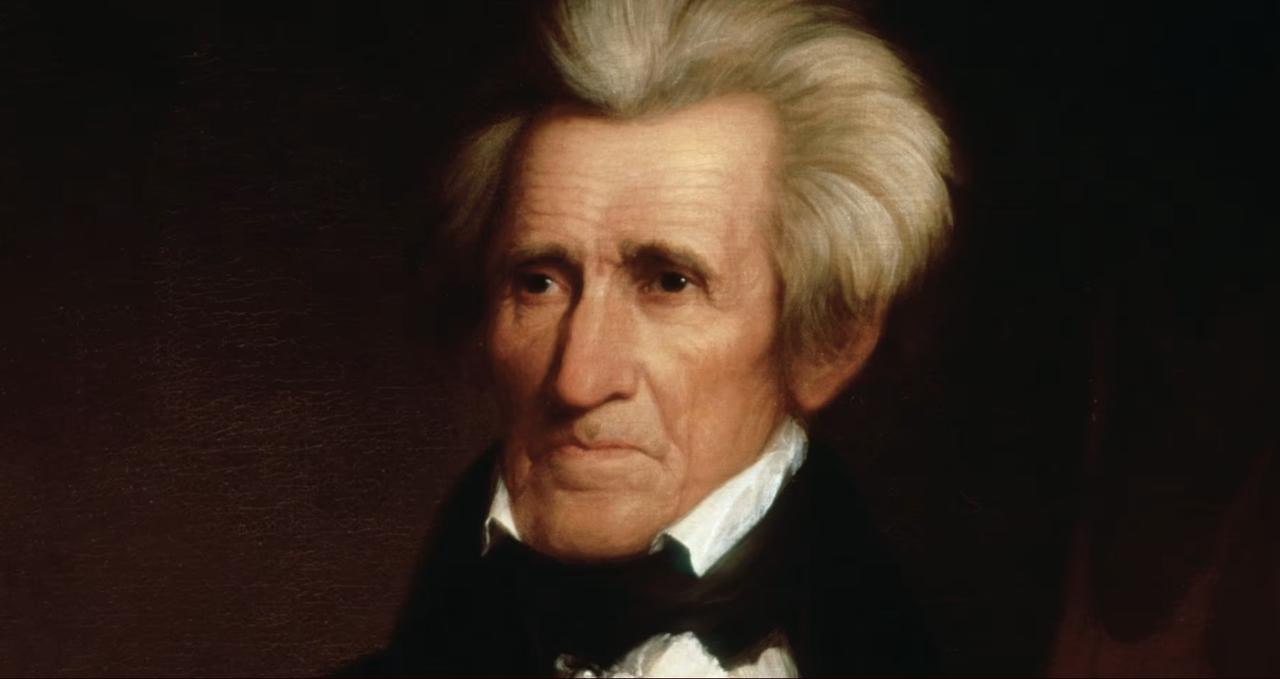

When the U.S. Senate rejected this secret article as potentially violating the Monroe Doctrine, the cooperation took a different form. American shipbuilders would work privately for the Ottomans, backed by quiet government support. U.S. President Andrew Jackson personally endorsed Henry Eckford before his departure, writing on April 20, 1831: "You sustain the reputation in this country, and I have no doubt deservedly, of being a naval architect of great skill and enterprise, and that I should count with confidence on a faithful performance of any engagement in the way of your profession."

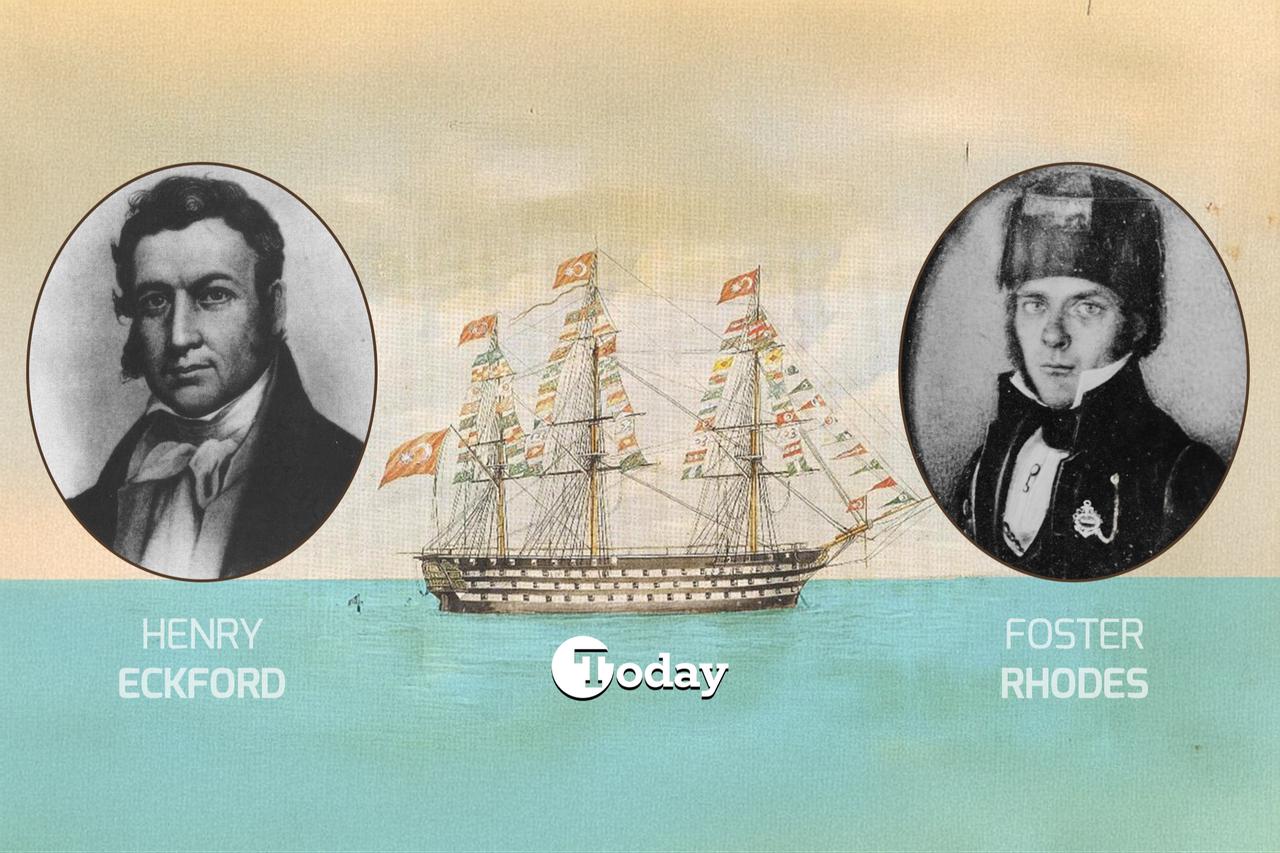

Henry Eckford was no ordinary contractor. Born in Kilwinning, Scotland, in 1775, he had earned a reputation as one of America's finest naval architects, called by North Ayrshire "the father of the U.S. Navy." His shipyard had built vessels for John Jacob Astor's fur empire and constructed crucial warships during the War of 1812, including the sloop-of-war Madison, built in just 40 days from cutting timber to launching.

After financial scandals and personal tragedies in New York—including the death of three adult children within a single year—Eckford departed for Istanbul in June 1831 aboard the corvette United States, which he hoped to sell to Sultan Mahmud II. The vessel itself was a masterpiece of American naval engineering: a 1,000-ton, 26-gun corvette that would demonstrate American capabilities to Ottoman officials.

When Eckford arrived in Constantinople in mid-August 1831, Sultan Mahmud II initially thought the United States had arrived as a gift from the American government. Once he learned it was for sale, he purchased it for $150,000, renaming it Mesir-i Ferah. On the top of that, he hired Eckford as his Chief Naval Constructor, beginning one of history's most forgotten yet impactful U.S. technology transfer program.

Eckford immediately began transforming the Imperial Arsenal at Constantinople, starting work on a small schooner, a frigate, and a 74-gun ship constructed using frames imported from New York City. His most ambitious project was designing the 128-gun ship-of-the-line Mahmoudieh. Sultan Mahmud II was so impressed that he considered granting Eckford a high imperial rank—extraordinary recognition for a foreign contractor.

But Eckford's vision extended beyond individual ships. He aimed to improve the technical infrastructure of the arsenal and educate Ottoman youth to become future naval engineers. The American approach emphasized not just building ships, but transferring knowledge and creating sustainable naval capabilities.

Eckford's rapid progress ended abruptly when he died suddenly in Constantinople on November 12, 1832, probably of cholera, just 15 months after his arrival. His body was shipped home aboard the barque Henry Eckford, but his work continued under his American foreman, Foster Rhodes.

If Henry Eckford laid the foundation, Foster Rhodes built the modern Ottoman navy. Rhodes served at the Imperial Arsenal from 1831 to 1839, and while Eckford is more renowned globally, Rhodes held greater influence within the Ottoman Empire, having served it for nearly seven years.

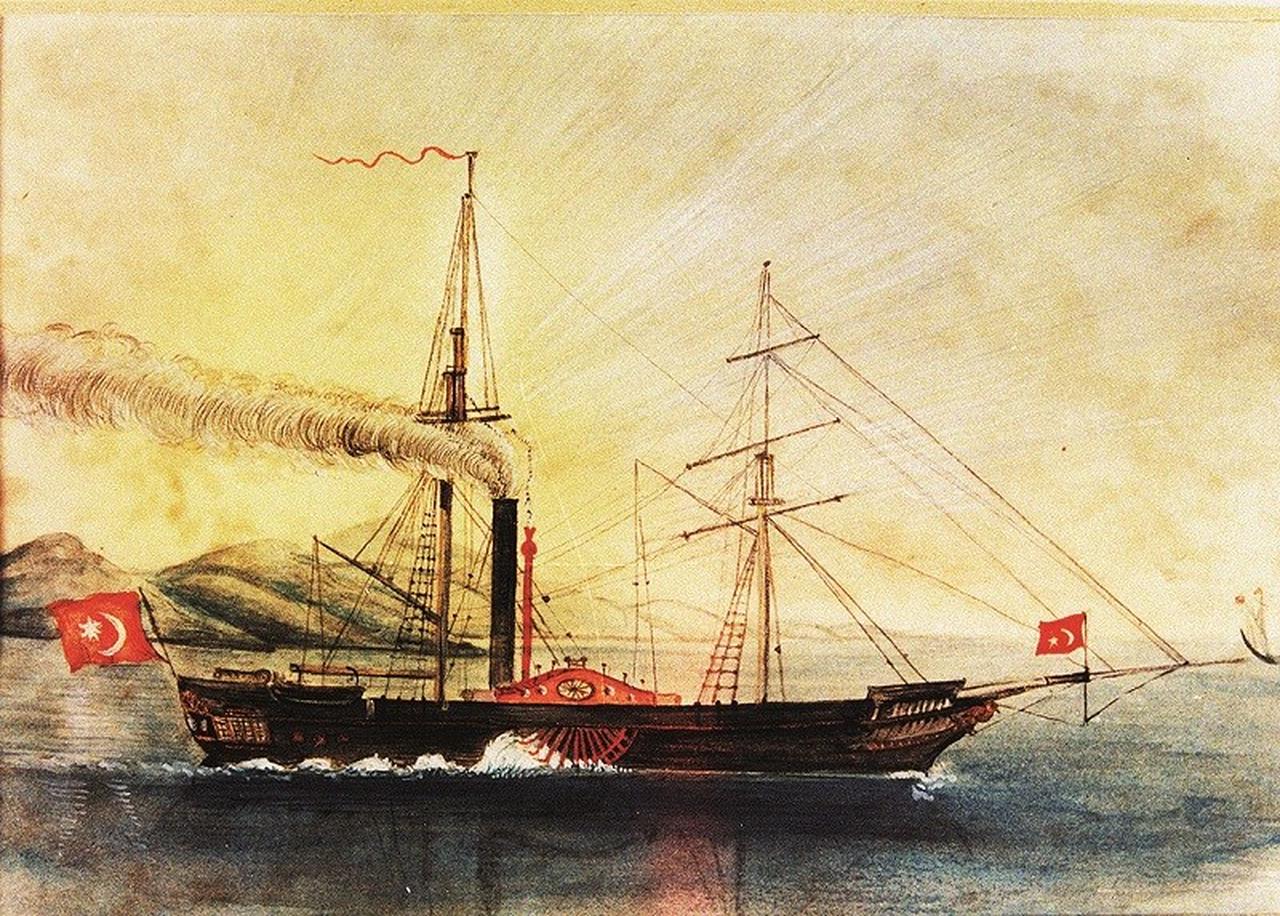

Rhodes achieved what many thought impossible: bringing steam power to the Ottoman fleet. In 1838, under the auspices of the American Foster Rhodes, the Imperial Arsenal produced its first steamship. The paddle steamer Eser-i Hayır was launched on November 26, 1837, followed by Mesiri-i Bahri in 1838 and Tair-i Bahri in 1839 from Aynalikavak Shipyard. Production of such vessels came as a technological leap comparable to the introduction of ironclads decades later.

Rhodes' contributions extended far beyond shipbuilding. The first ship built by Rhodes was the Neveser (1834) followed by the Nusretiye galleon, and the Tarz-Cedit a year later. The Nizamiye frigate, the Kafs-i Zafer brig, and the Mujderesan were commissioned a year later. Each ship incorporated American innovations in design and construction techniques, gradually modernizing Ottoman naval capabilities.

The American engineer also showed exceptional cultural adaptability. Like Eckford, Rhodes earned significant respect and prestige, even drawing the attention of the Sultan. He took pride in the achievements of Ottoman carpenters and apprentices trained at the Imperial Arsenal. In one incident, when a Turkish official spoke to him abusively, Rhodes struck him on the head with his pipe. Despite this, the Sultan did not take any action against his trusted American builder.

The American naval mission’s influence reached well beyond the Imperial Arsenal. Both Eckford and Rhodes helped secure access to Sultan Mahmud II for the U.S. diplomatic delegation—an opportunity that would have been unlikely given the relatively low rank of David Porter, the charge d’affaires in Istanbul. Their technical skills achieved what conventional diplomacy alone could not.

The Americans also contributed financially to the missionaries through personal donations, but more significantly, they offered the crucial network and respect needed to establish schools serving the Muslim population. This laid the groundwork for a lasting American influence in education that would continue for decades.

The relationship proved mutually advantageous. Thanks to the reputation built by Eckford and Rhodes, American naval officers visiting Constantinople were received with great respect. Serving in the Ottoman Empire became a prestigious assignment, advancing naval careers and offering important experience in international collaboration.

The American involvement came at a crucial moment in Ottoman history. Sultan Mahmud II faced multiple crises: the Greek War of Independence, the Egyptian-Ottoman War, and rising pressure from European powers. In 1831, Egyptian forces under Ibrahim Pasha had captured all of Syria and were advancing toward Istanbul itself, forcing Mahmud II to seek Russian assistance through the Treaty of Hunkar Iskelesi.

The Sultan distanced himself from the British, French, and Russians as a result of his empire’s growing ties with the United States. Through American technology transfer, the Ottomans gained access to modern capabilities without the political entanglements that typically accompanied European assistance.

The timing was perfect for American interests as well. The Monroe Doctrine had declared opposition to European expansion in the Western Hemisphere, but it said nothing about American expansion of influence in the Eastern Hemisphere. The Ottoman partnership allowed the United States to project technological and cultural influence into a strategically vital region without direct political entanglement.

The American contribution extended beyond designing individual ships to driving fundamental advancements in Ottoman naval technology. The introduction of steam power in 1837 marked a major leap in shipbuilding, bringing the Ottoman fleet closer to the world’s leading naval powers.

Rhodes and his team implemented American construction methods, laying the groundwork for domestic ship industries that aimed to produce steam engines, paddle wheels, and a rolling mill at the Imperial Arsenal. They also established a distinct American section within the shipyard—operated entirely under American supervision and regulations.

The knowledge transfer was comprehensive. Ottoman workers learned American methods of iron forging, precision measurement, and quality control. The educational component was crucial—both Eckford and Rhodes emphasized training local personnel who could continue the work after their departure.

The American mission’s impact endured well beyond Rhodes’ departure in 1839. The Ottoman navy had gained more than just new ships—it had developed enhanced capabilities and a sense of technological confidence. By the 1860s, naval modernization picked up pace with renewed American cooperation, as the Ottomans intensified their search for arms and began considering the United States as a key supplier.

The relationship established patterns that would recur throughout U.S.-Türkiye relations: Technology transfers, military cooperation, and mutual benefit despite different political systems. The success of the 1830s naval mission provided a template for future defense partnerships, from World War II lend-lease programs to modern F-35 fighter jet cooperation.