In the early 1930s, as imperial ambitions clashed across Asia, Japan launched an audacious but ultimately unsuccessful geopolitical maneuver: to establish a puppet state in East Turkestan with Prince Abdul Kerim Efendi—grandson of Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II—as its head of state and Caliph. Uncovered intelligence reports from Japanese archives shed light on how this plan was foiled by a rare alliance between Türkiye and the Soviet Union.

Following its military victories over China (1895) and Tsarist Russia (1905), Japan pursued a strategy of territorial expansion, guided by the ideology of “Greater Asianism.” This belief promoted unity among Asian peoples under Japanese leadership and sought to expel Western influence. The Japanese government, aided by ultra-nationalist societies like Kokuryukai and Genyousha, viewed Muslim Turkic populations in Central Asia as potential allies in reshaping the continent's future.

By the early 1930s, Japan had already established Manchukuo as a puppet state in Manchuria and aimed to apply a similar model in East Turkestan, a region under Chinese control but home to Turkic Muslim populations. In this context, Prince Abdul Kerim Efendi emerged as a symbolic figure who could lend legitimacy to a new Islamic state envisioned by Japanese strategists.

On May 21, 1933, Prince Abdul Kerim Efendi arrived in Tokyo via Bombay, Singapore, and Shanghai. Welcomed by nationalists and student groups shouting “Banzai,” his presence quickly became a source of diplomatic tension. He maintained publicly that his visit was part of a broader world tour and denied having any political motives. “I came to see Japan and to visit the tomb of Emperor Meiji and Turkish martyrs,” he told local press, dismissing Russian reports that he intended to become the ruler of a future East Turkestan state.

Despite these denials, intelligence from multiple sources suggested otherwise. Japanese military factions and ultra-nationalists viewed the prince as a potential leader who could unite Turkic Muslims under a state loyal to Japan. His status as a descendant of the Ottoman dynasty and former heir to the Caliphate gave him symbolic weight in the Muslim world.

The possibility of an Ottoman prince reclaiming political and religious authority abroad alarmed both Türkiye and the Soviet Union. The Soviet leadership feared instability along its borders and the emergence of a state that might inspire Muslim populations within its territory. Meanwhile, Türkiye—having abolished the Caliphate in 1924 and shifted away from its Ottoman past—sought to block any attempt to revive dynastic influence abroad.

An indirect but strategic counter-effort was launched. Two prominent Tatar leaders—Ayaz Ishaki and Abdurreshid Ibrahim—visited Japan around the same time and worked to shift the loyalties of the Turkic diaspora away from Japanese influence. Ishaki later helped establish the Idil-Ural Turk-Tatar Cultural Society, which promoted ties with Türkiye instead. This maneuver eventually undermined the position of Japan-aligned Tatar figure Molla Abdulhay Kurbanali, who was expelled from Japan in 1938 despite resistance from nationalist circles.

One of the more dramatic episodes involved a Turkish man named S. M. Osman Bey, a former Soviet intelligence officer and ex-consular clerk, who arrived in Japan in August 1933. Claiming to have loaned Prince Abdul Kerim 10,000 yen—a significant amount at the time—he threatened to expose the prince’s alleged fraud unless repaid.

According to intelligence reports, Osman was suspected of working with Soviet and Turkish authorities. His legal battle against the prince unfolded with the quiet involvement of Türkiye’s embassy in Tokyo, whose attorney also represented Osman in court. The legal and diplomatic pressures, combined with growing scrutiny from Soviet and Turkish observers, appear to have played a role in halting the prince’s political trajectory.

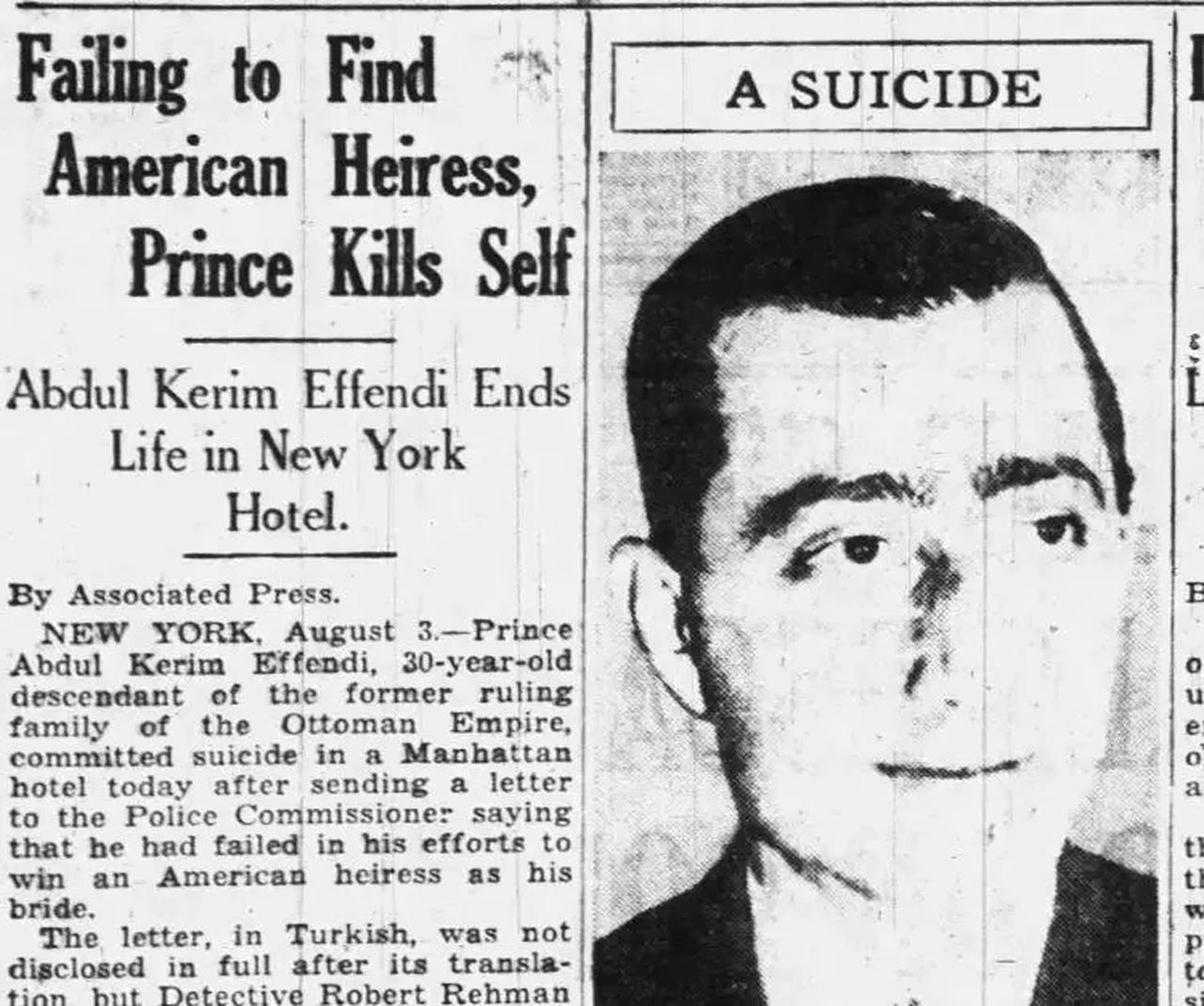

The plan to install Prince Abdul Kerim as the ruler of East Turkestan ultimately failed. He left Japan for the United States, where he died by suicide in a hotel room. His death was officially recorded as a suicide, but those close to him and his relatives claimed it was murder, blaming the Japanese, who they believed were seeking revenge for a failed Turkestan policy.

Japanese ambitions for a Central Asian client state were shelved as their strategic focus shifted toward Southeast Asia and the Pacific.