Recent drug operations, particularly those involving well-known public figures, have once again brought the issue of narcotics to the public agenda.

However, Türkiye’s struggle against drugs and banned substances dates back centuries. Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire, which applied Islamic law, waged a relentless fight against intoxicants.

Despite claims circulating on social media suggesting that alcohol, opium and cannabis were widespread and freely consumed in the Ottoman period, historical realities paint a very different picture.

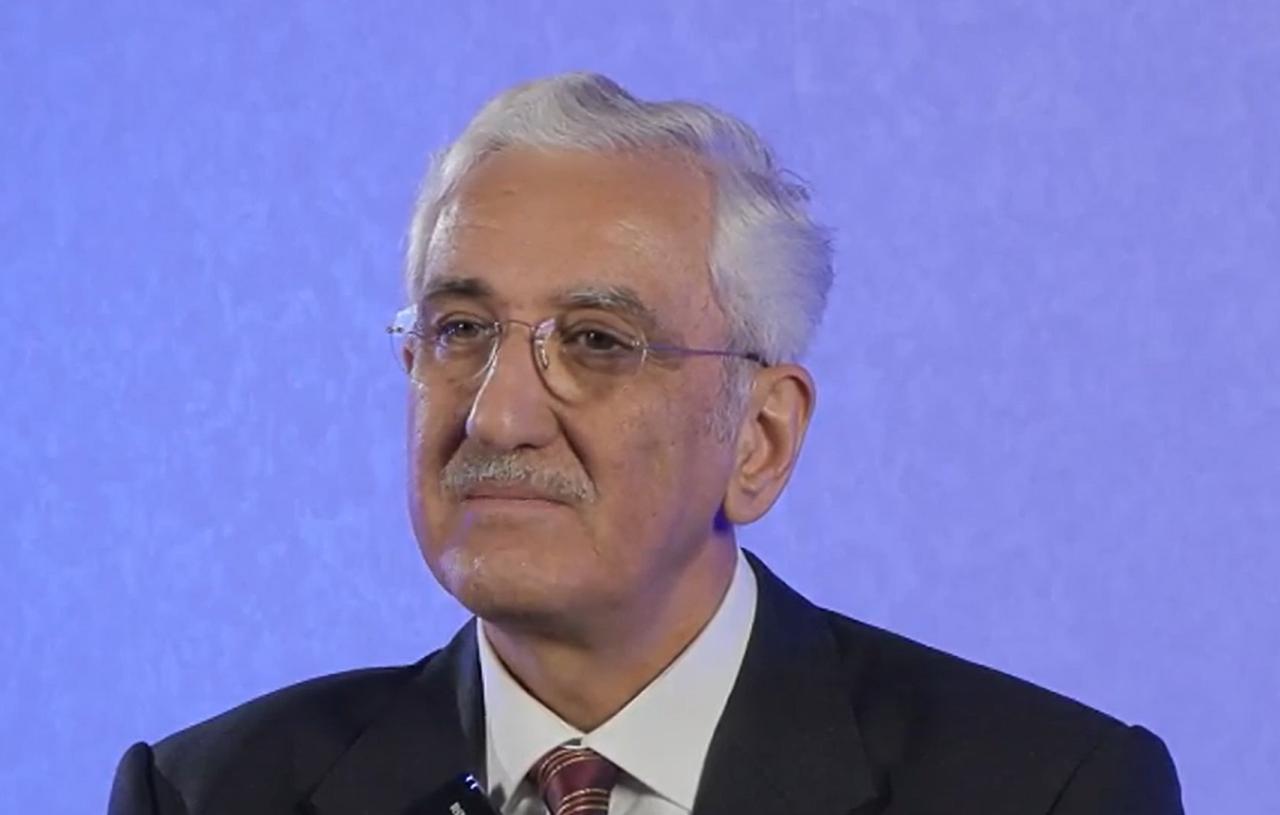

The use of drugs and pleasure-giving substances in the Ottoman Empire has long been one of the most debated subjects in history. Some substances were banned only for Muslims, while others were forbidden for everyone. To clarify the most controversial questions, we spoke with Professor Ekrem Bugra Ekinci, who teaches Ottoman law.

Ekinci shared striking examples, noting that some grand viziers and statesmen were personally tested by the sultan, and stressed that the Ottoman state maintained a continuous struggle against intoxicants.

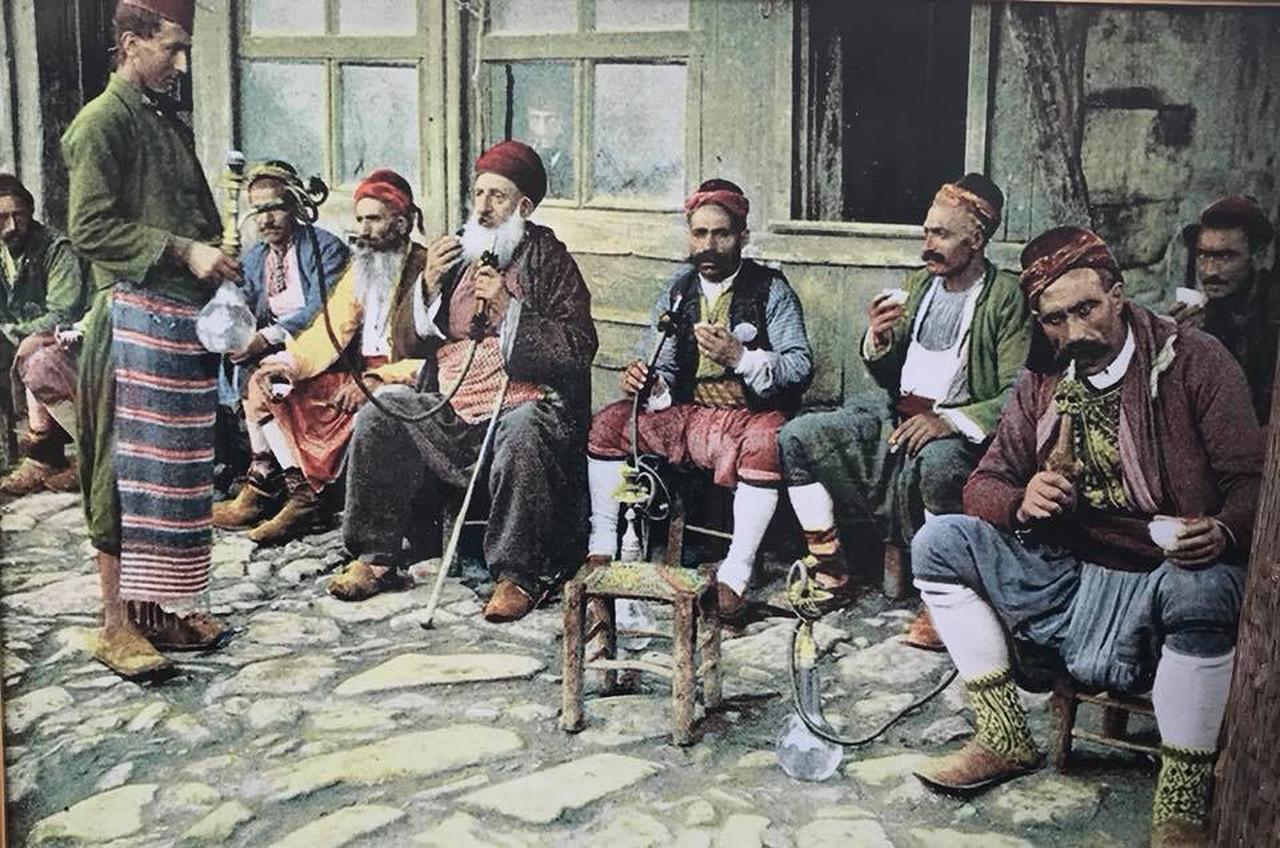

Ekinci explains that tobacco was never given a definitive religious ruling in the Ottoman Empire and that scholars held differing opinions on the matter. However, he emphasizes that the fight against tobacco was often misunderstood.

“In the Ottoman Empire, tobacco was not primarily a religious issue but a political and social one,” he says.

Many of Istanbul’s devastating fires were caused by negligence while smoking at night, making strict bans unavoidable.

According to Ekinci, alcohol and drugs were clearly forbidden in Islam, but tobacco remained a disputed issue among scholars. Some considered it religiously harmful, others saw it as permissible but disliked.

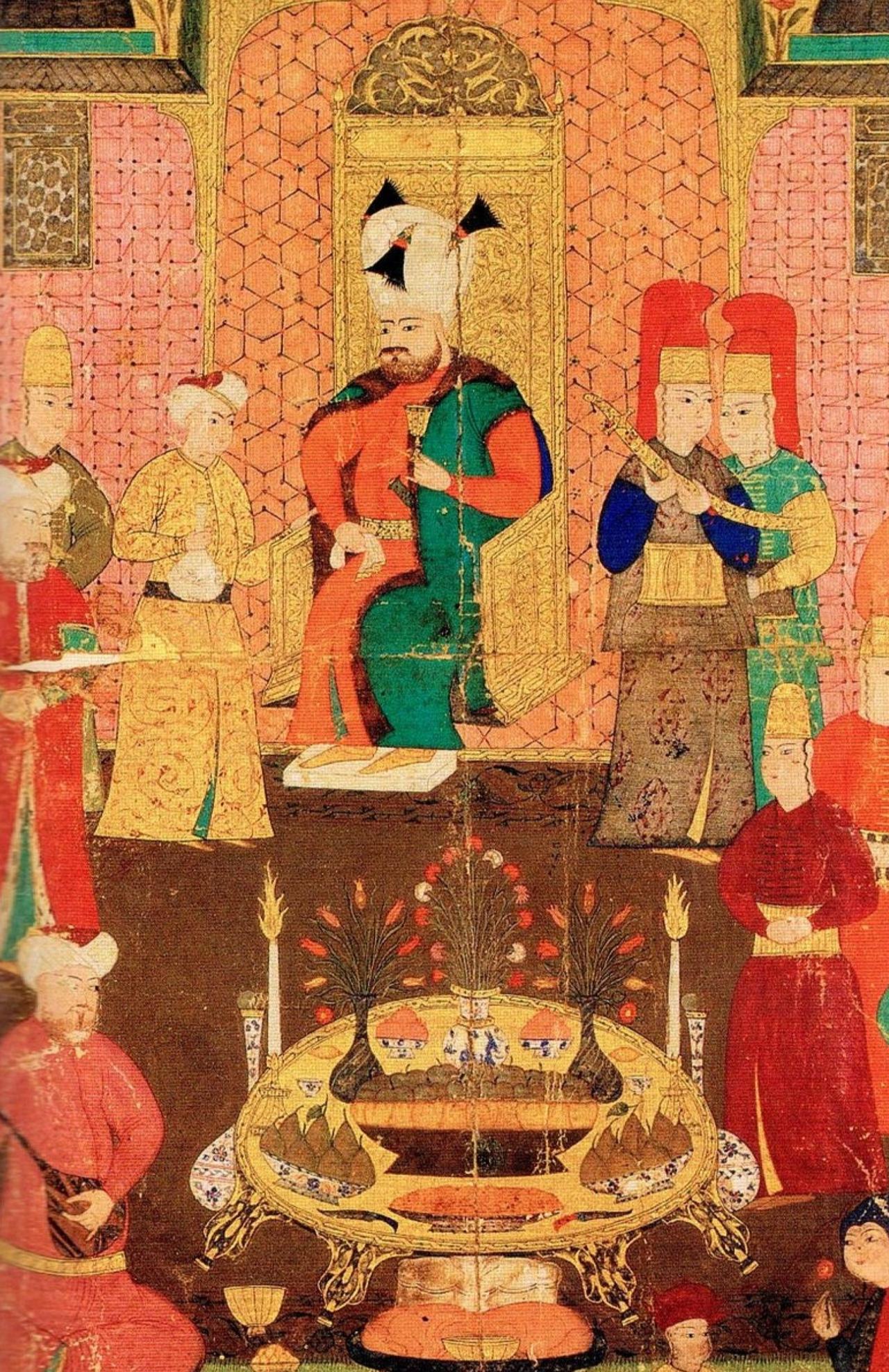

The harshest enforcement of tobacco bans took place during the reign of Sultan Murad IV, a period marked by severe political instability.

“In the 17th century, political discussions were not tolerated,” Ekinci explains.

“Murad IV ruled after a period of great anarchy. He did not forgive gatherings formed under the pretext of smoking, because they often turned into political discussions.”

Professor Ekinci underlines that alcohol could not be consumed openly in Ottoman society and was only legally permitted for non-Muslims.

“Was alcohol consumed in the Ottoman Empire? Of course it was. Was it produced? Yes. But this was done by non-Muslims,” he says.

“For non-Muslims, producing, selling and drinking alcohol was allowed as part of religious freedom. Muslims, however, could not drink alcohol or visit taverns.”

He adds that Muslims who drank did so secretly, and the state intervened whenever it became aware.

Under Islamic law, a Muslim could not legally own wine. If someone broke or spilled a Muslim’s wine, no compensation was required. However, the same act against a non-Muslim’s wine would require compensation.

Ekinci explains that intoxicants such as opium and cannabis were largely used for medical purposes and functioned similarly to today’s “red prescription” drugs.

“Narcotics such as cannabis and other substances are not all the same,” he says.

“Some were used as medicine. At a time when pharmacy was underdeveloped, alcohol and drugs were sometimes prescribed for treatment.”

If medical science declared alcohol necessary for treatment, it became permissible strictly as medicine, not as a pleasure-giving substance. Such decisions could only be made by a competent and morally responsible Muslim physician.

However, due to the high risk of abuse, strict controls were imposed.

“Misuse was never tolerated. Those who used drugs did exist, but never openly. Once it became public, prosecution followed.”

Stories of opium and cannabis addicts often reflect the empire’s unofficial, hidden life rather than state-sanctioned behavior.

Ekinci recounts a striking anecdote about Ozdemiroglu Osman Pasha, the conqueror of the Caucasus.

Rumors reached the sultan that Osman Pasha was addicted to cannabis. Enraged, the sultan summoned him and asked him to recount the Caucasus campaign in detail.

“He described the mountains, rivers, troop movements for hours,” Ekinci says.

“Afterwards, the sultan said: ‘They lied. A cannabis addict could not endure this long without showing symptoms.’”

No signs of addiction were detected, and the accusation was dismissed.

Ekinci warns against misinterpreting historical anecdotes.

During the reign of Sultan Murad IV, a physician named Emir Celebi was accused of opium addiction. The sultan invited him to play chess.

As the game dragged on, Celebi began sweating, blushing, and trembling. When searched, opium was found in his possession, confirming the accusation. He was punished accordingly.

However, Ekinci stresses that such incidents were extreme exceptions.

“The fact that something is frequently mentioned in historical narratives does not mean it was widespread,” he says.

“On the contrary, it means it was rare and considered shocking.”

Stories about alcohol and drugs survived precisely because they were unusual and scandalous, often exaggerated over time.

“Every society, even those of prophets, has had individuals with addictions,” Ekinci concludes.

“The Ottoman society was no exception. But such practices never became widespread, normalized, or official.”

The Ottoman state consistently fought intoxicants to the best of its ability, and substance abuse never became a natural or accepted part of Ottoman social life.