For much of its six-century history, the Ottoman Empire sustained a sophisticated and evolving engagement with astronomy, one that was deeply embedded in education, governance, and daily life. Far from being a marginal or purely traditional pursuit, astronomy in the Ottoman world developed through observation, calculation, and institutional support, while remaining responsive to scientific developments beyond its borders.

Scholars of the history of science note that Islamic civilization attached particular importance to the organization of time. Daily prayers, annual religious observances, navigation, agriculture, and imperial administration all depended on accurate astronomical knowledge. This practical necessity ensured that astronomy remained a central scientific discipline from the earliest centuries of the Ottoman state.

Salim Ayduz, “Ottoman Contributions to Science and Technology” (2010) notes that the foundations of Ottoman astronomy were inherited from earlier Islamic scientific centers, including Seljuk Anatolia, Cairo, Damascus, and Samarkand. As the empire expanded, new intellectual hubs emerged in cities such as Bursa, Edirne, Istanbul, and Amasya. These centers were supported by madrasas, which are educational institutions funded by charitable endowments that taught astronomy alongside mathematics and logic.

The conquest of Istanbul in 1453 marked a turning point. Sources from the period suggest that Sultan Mehmed II actively patronized scientific scholarship, attracting scholars from across the Islamic world and beyond. The Sahn-i Saman madrasas he established functioned as a university-like complex where astronomy was taught systematically and treated as a mathematical science rather than speculative philosophy.

Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu argues in his work on Ottoman science that one of the most influential figures of this period was Ali Qushji, a scholar trained in the Samarkand astronomical tradition. His arrival in Istanbul introduced a new emphasis on mathematics and observation. Rather than grounding astronomy in Aristotelian metaphysics, Qushji argued that celestial models should be judged by their mathematical consistency and observational accuracy.

This approach represented a quiet but significant shift. Astronomy could evolve without challenging religious belief, allowing Ottoman scholars to refine astronomical models while preserving intellectual continuity with the Islamic past.

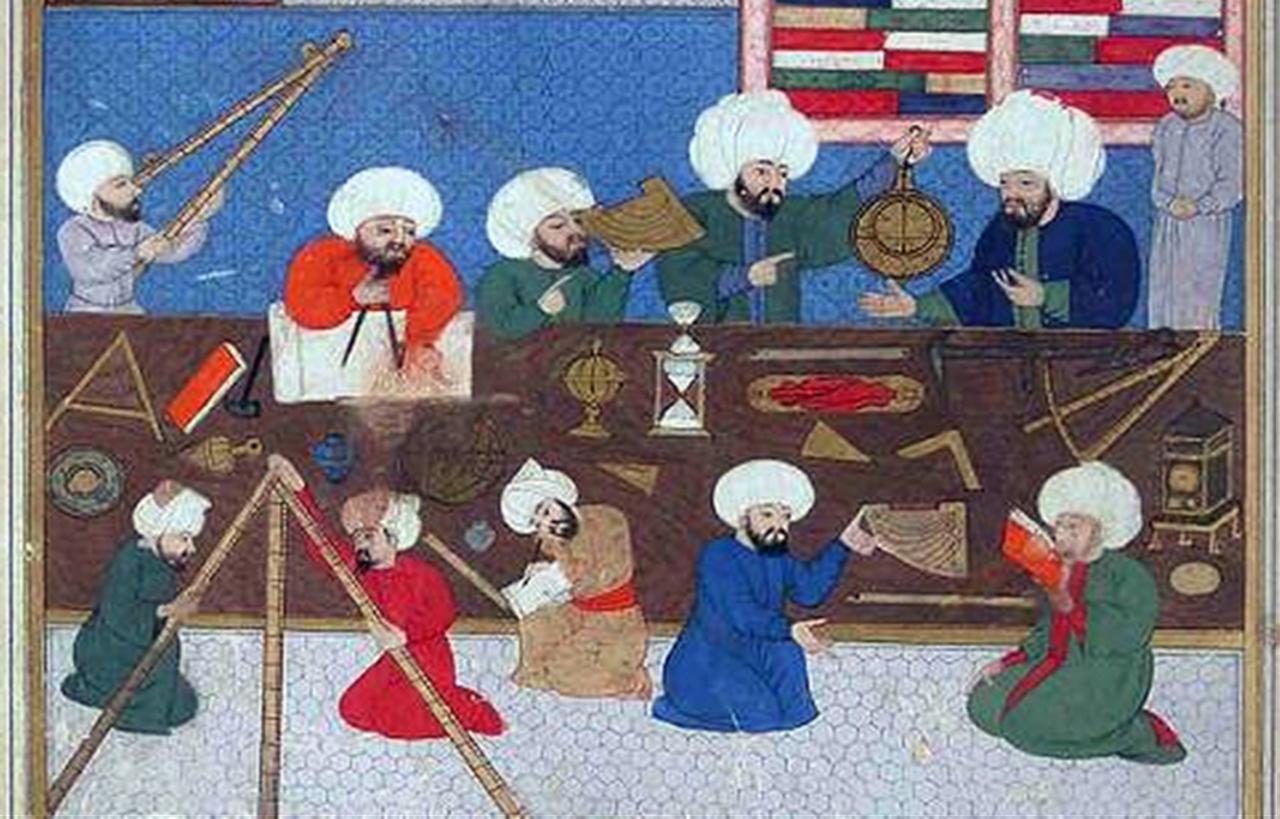

The most ambitious expression of Ottoman astronomy emerged in the late sixteenth century with the establishment of the Istanbul Observatory. Ayduz further observes that it was founded in 1577 under the direction of Taqi al-Din, one of the empire’s most accomplished astronomers.

The observatory housed advanced instruments and mechanical clocks capable of measuring time in seconds, a crucial innovation for precise astronomical observation. Experts on Islamic astronomy note that these tools placed Ottoman astronomy on par with contemporary European observatories. Although the institution was dismantled only a few years later, historians agree that this event did not mark the end of Ottoman astronomy but rather a shift in how and where it was practiced.

Studies of Islamic and Ottoman calendars reveal that astronomy in the Ottoman Empire was inseparable from timekeeping. The Islamic lunar calendar regulated religious life, while solar calendars were used for taxation and agriculture. The Ottomans employed multiple systems simultaneously, including the Hijri lunar calendar and the Rumi calendar derived from the Julian system.

Astronomers were responsible for producing calendars, almanacs, and perpetual tables known as Ruznames. According to surviving manuscripts, these works listed prayer times, eclipses, zodiacal positions, and the correspondence between different calendar systems. Such tools ensured that astronomical knowledge was not confined to scholars but circulated widely among administrators, navigators, and religious officials.

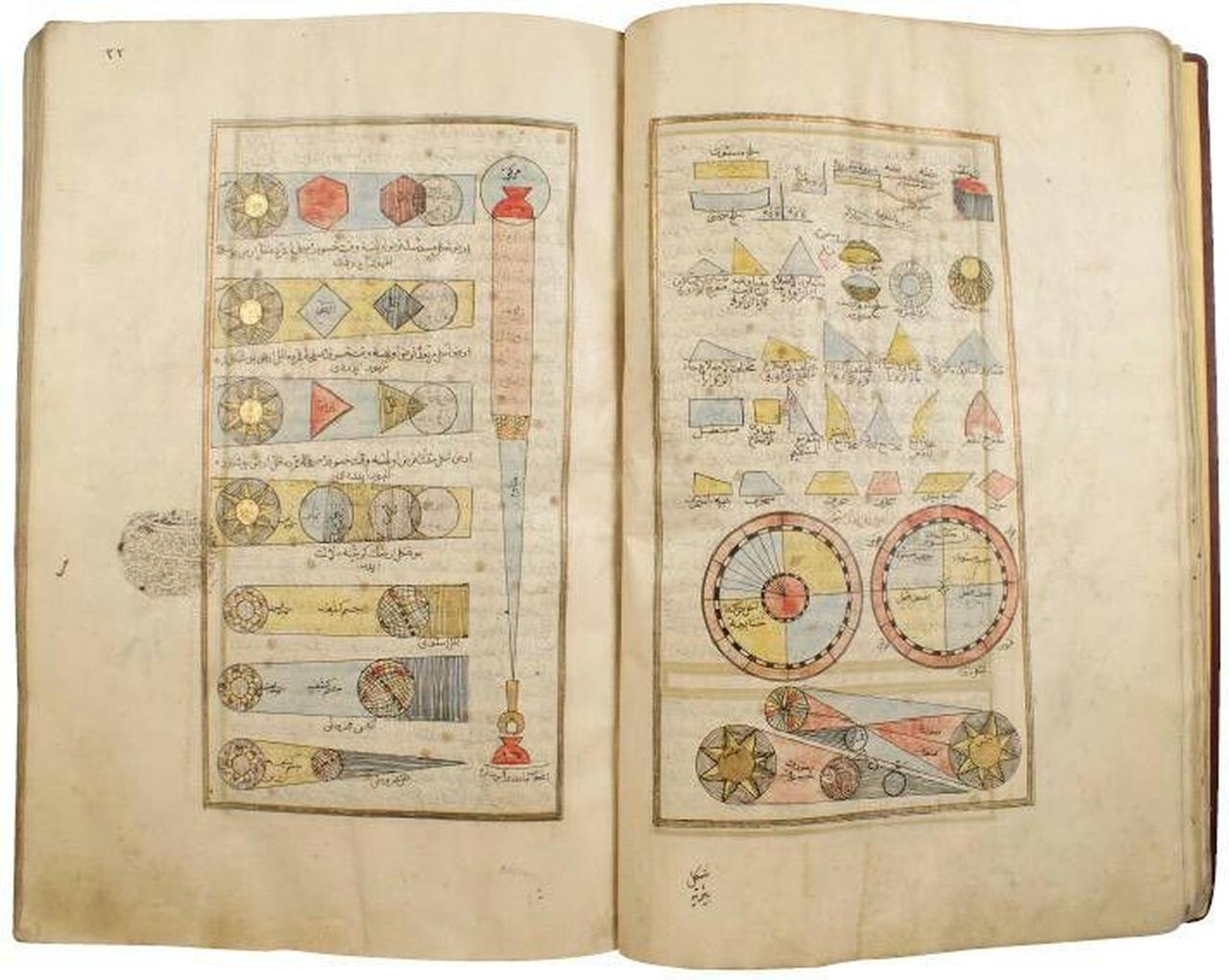

According to Gaye Danisan, one of the most overlooked aspects of Ottoman astronomy is the use of paper instruments. These included circular volvelles, calendar converters, celestial diagrams, and educational tools designed to simplify complex calculations.

Manuscripts preserved in Istanbul and Bursa libraries contain movable paper devices that allowed users to determine the beginnings of lunar months, convert between calendars, and calculate prayer times. Danısan further explains that these instruments reveal a hands-on scientific culture in which astronomy was practiced through tangible, portable means rather than confined to observatories alone.

One notable example is the celestial map Mirʾat al-Samaʾ (“Mirror of the Sky”), attributed to Hoca Tahsin Efendi in the nineteenth century. Annotations found in surviving manuscripts reveal that it was designed to depict the visible sky across much of the Ottoman realm, reflecting an effort to localize astronomical knowledge geographically.

According to studies of the Tulip Era (1718–1730), astronomy also benefited from cultural flourishing and translation projects. Under the patronage of Grand Vizier Nevsehirli Damat Ibrahim Pasha, teams of scholars translated major works into Ottoman Turkish.

One such translation included sections on astronomy and geography from a fifteenth-century world history by Bedreddin al-Ayni. According to the manuscript, the translator Mirzazade Salim Efendi not only corrected astronomical details but also added detailed miniature illustrations of zodiacal constellations and fixed stars. These images followed the tradition of Ptolemy’s star catalog and demonstrate how visual representation played a role in astronomical education.

It is often assumed that the Ottoman Empire arrived late to modern astronomy and resisted its adoption. Yet the historical evidence tells a more complex story. Research by Orhan Gunes on Ottoman paper astronomical instruments reveals sustained scholarly engagement with astronomical calculation, measurement, and pedagogy across several centuries.

Gunes demonstrates that Ottoman madrasa scholars discussed newly discovered planets earlier than previously believed. Uranus, identified as a planet in 1781, appears in an Ottoman astronomical work written in 1831. Neptune, discovered in 1846, is discussed in a text published in 1848. Gunes further argues that these works originated not from Western-style engineering schools but from traditional madrasa circles.

This evidence challenges the idea that Ottoman religious institutions resisted scientific change. Instead, astronomy continued to be taught in parallel across madrasas, observatories, and modern schools throughout the nineteenth century.

According to historians of Ottoman science, astronomy in the empire was characterized by continuity rather than collapse. Scholars often retained geocentric models for positional calculations while acknowledging heliocentric cosmology when observationally necessary. This pragmatic approach reflected astronomy’s long-standing reliance on mathematical effectiveness rather than philosophical allegiance.

From Ali Qushji’s mathematical reforms to Taqi al-Din’s precision instruments, from calendar makers to paper instruments, and from illustrated star catalogs to early discussions of modern planetary discoveries, Ottoman astronomy reveals a scientific tradition that was adaptive, institutionalized, and deeply practical.

Rather than standing outside the history of science, the Ottoman Empire was an active participant in humanity’s enduring effort to understand the cosmos.