In the 19th century, as European empires expanded their influence and museums raced to stockpile antiquities, the island of Cyprus, then under Ottoman rule, became a key battleground for archaeological exploration.

British diplomats, collectors, and scholars led extensive excavations, transporting thousands of ancient artifacts to London and beyond, often with little regard for local heritage protections.

The findings of Rehsan Yildiz, published in Education and Society in the 21st Century, shed light on the wide-reaching impact of British archaeological activities on Cyprus' cultural legacy.

From the Hittites to the Ottomans, Cyprus has long been home to a rich tapestry of civilizations. Yet by the 1800s, its ancient heritage became the object of Western fascination.

British archaeologists, driven by scholarly ambition and imperial prestige, began unearthing artifacts from sites like Salamis, Dali, and Kition.

Among the most active figures was Robert Hamilton Lang, a banker-turned-explorer who operated with considerable freedom thanks to his diplomatic status.

Lang helped smuggle massive statues and rare inscriptions from the island to Britain, sometimes disguising them as corpses to evade customs officers.

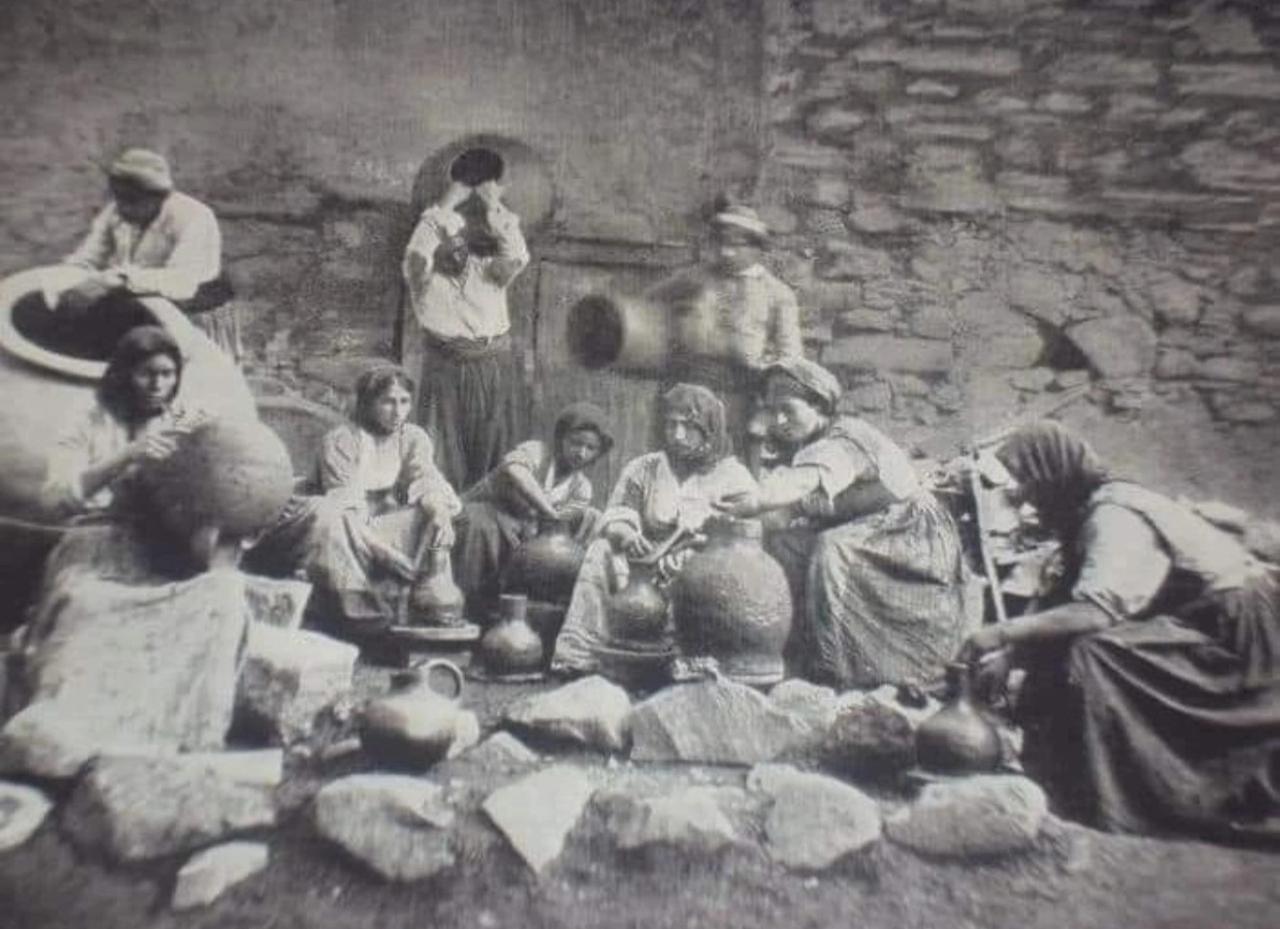

One of the most famous episodes took place in Dali (ancient Tamassos), where a torrential rainstorm in 1868 exposed a wealth of ancient pottery. Local villagers alerted foreign archaeologists, sparking a frenzy of activity. British, French, and American teams raced to claim the treasures.

Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an American consul, quickly rose to prominence.

He amassed more than 35,000 artifacts—many illegally exported—and eventually sold them to major institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cesnola’s finds occupied four galleries and became some of the museum's earliest acquisitions.

The Ottoman Empire attempted to stem the tide through a series of legal reforms known as the Asar-i Atika regulations, enacted in 1869 and 1874. These aimed to control excavations and ensure that a portion of the artifacts remained within the empire.

Despite these efforts, diplomatic immunity, vague laws, and Western political pressure made enforcement difficult. In several instances, Ottoman officials like Said Pasha intervened directly, halting artifact exports and reclaiming statues for transfer to Istanbul.

Yet even these successes were partial. Cesnola and his peers continued their activities, aided by foreign embassies and colonial ambitions.

The British-led excavations in Cyprus reflect a broader pattern of 19th-century imperial archaeology, where knowledge, profit, and power were often inseparable. While museums in London, Paris, and New York proudly displayed Cypriot artifacts, the island itself was left with a fragmented cultural record.

The case of Cyprus stands as a potent example of how archaeology can both illuminate and erase the past—depending on who holds the spade.