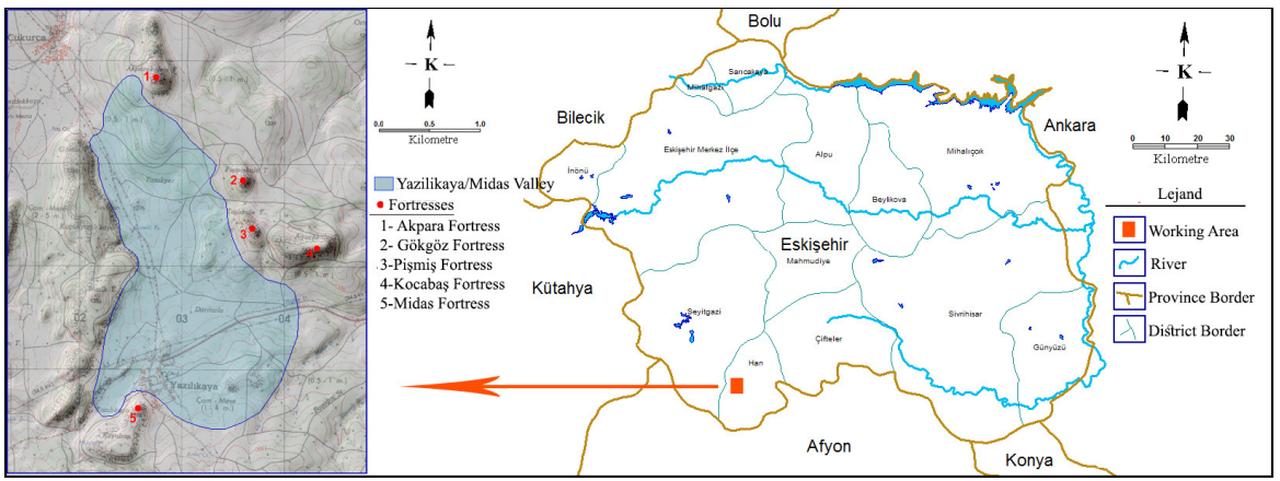

A targeted excavation in front of the monumental Phrygian rock‑cut altar at Yazilikaya/Midas Fortress has brought out a ritual preparation area: rock‑cut bowls, hearths used to cook sacrificial animals, an abstract idol of the Mother Goddess Matar, and a sequence of ceramics showing use from the Middle Phrygian period into Hellenistic and Roman times.

Archaeologists carried out campaigns in 2022 and 2024 aimed at tracing architectural remains and the stratigraphy immediately west of the acropolis. In trenches opened in front of the large rock‑cut altar (an altar carved directly into bedrock rather than built up from loose stones) they dug up mixed Phrygian, Lydian and Roman ceramics, a pithos (large storage jar used for grain, oil or wine) and craters (large pottery vessels used for mixing or serving), loom weights and spindle whorls, a hearth connected to the altar, and three shallow rock‑cut bowls set on a leveled platform.

The finds point to a site that was set up in the Middle Phrygian period (eighth–seventh century B.C.) and kept on being used and reshaped well into Hellenistic and Roman times.

Excavators revealed a variety of built elements: a wall laid in dry masonry, a stone pavement fragment, pits and a rudimentary stone foundation likely capped by a wooden superstructure, and a hearth that appears to have served for cooking animals sacrificed during ceremonies.

The rock‑cut bowls—roughly 25 centimeters across and shallow in depth—sit near an abstract rock idol interpreted as a depiction of Matar and together signal an area arranged for offering acts and food preparation. The trench work and stacked fills show how the team cut down to bedrock and leveled the sloping ground to set up these ritual fittings.

Fieldwork in the nearby village of Cukurca, about 3.5 kilometers north of the site, brought useful parallels. Wooden bowls used by villagers to leaven bread closely match the form of the rock‑cut bowls, and a local kotlan hearth resembles the quadrangular hearths uncovered south of the altar.

These continuities do not prove identical ritual meanings, but they do bear out functional similarities in food preparation and heating that help interpret the archaeological context.

The team also recovered evidence for weaving and daily life at the sanctuary in the form of weights and spindle whorls.

The area has long been associated with cultic activity: earlier work in the 1930s had already turned up terracotta figurine fragments and Greek‑inscribed votive stelae (a carved stone slab set up as a dedication to a deity) dedicated to Agdistis, suggesting a maintained sanctity under Hellenistic and Roman names.

A Roman coin dated to the Dokimeion Agrippina II period was also found in the same sector, reinforcing the picture of continuous or recurring sacred use across centuries. The recent excavations, therefore, bring into clearer focus a ritual preparatory zone that was adapted through time rather than abandoned.

The excavations in front of the Phrygian rock‑cut altar at Yazilikaya/Midas Fortress have revealed a bounded ritual preparation area with hearths, bowls and structural elements that together demonstrate organized ritual activity in the Phrygian period and its continuation into later eras.

Further detailed study of bone remains and stratified deposits will be needed to clarify specific ritual sequences and food practices.