Balbals—stone statues erected on the wide steppes of Central Asia—stand as silent witnesses to the ancient past of the Turkic world. These weather-worn figures, once believed to guard the spirits of the dead or mark the graves of fallen warriors, stretch across a vast geography from Mongolia to the Balkans, embodying centuries of belief, cultural continuity, and artistic expression.

In the lands that now include Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and the Republic of Türkiye, these sculptures—ranging from abstract steles to humanlike figures with swords or cups—reveal deep connections between the living and the spiritual realm. Their survival into the present day has not only captivated archaeologists and historians but has also fueled a broader cultural resurgence across Turkic states.

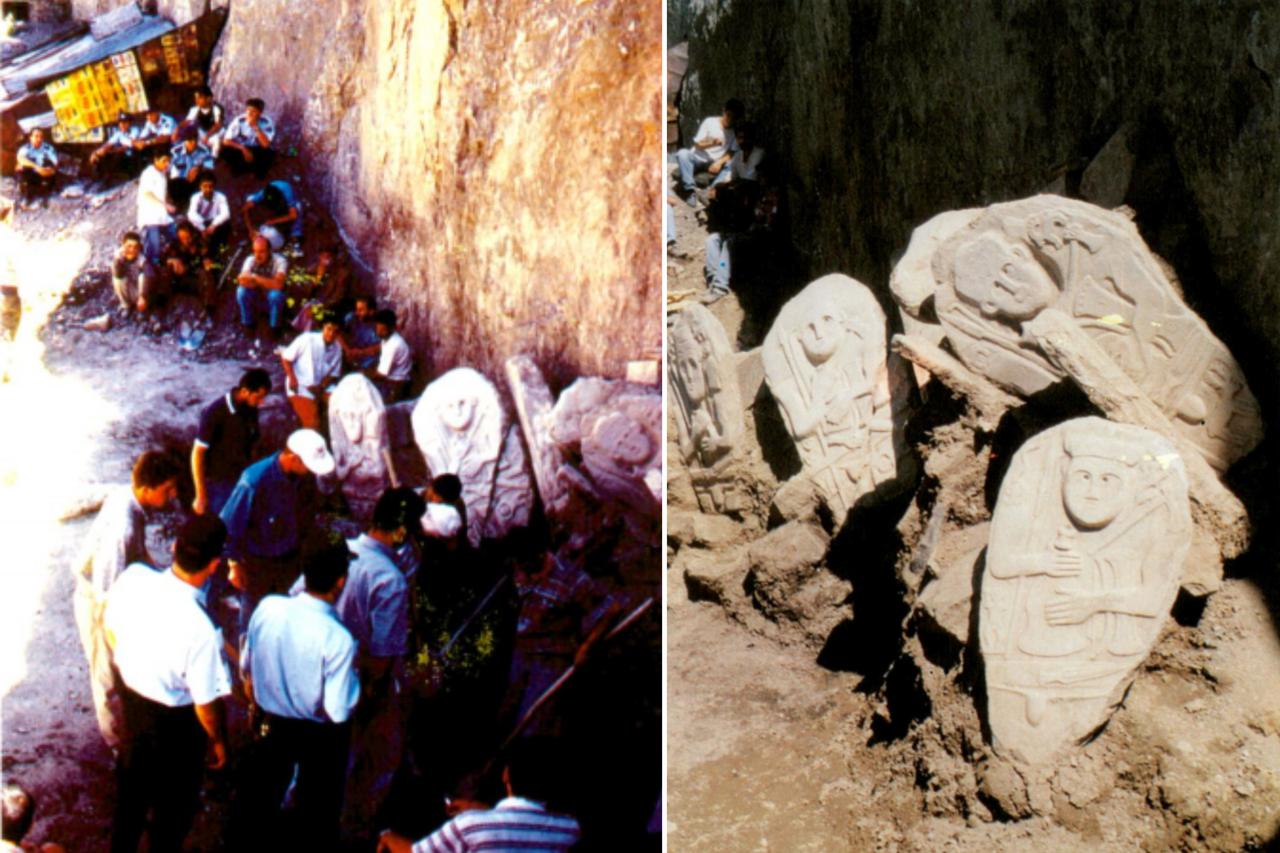

Balbals or Kurgan stelae are not mere relics of artistic expression; they functioned as powerful tools of remembrance in the nomadic societies of the early Turkic peoples. These stone statues often lined ritual spaces or burial mounds, each one believed to represent an enemy defeated by the deceased. The more balbals found around a grave, the greater the reputation of the buried warrior.

According to scholars, this practice not only highlighted the individual's martial prowess but also reaffirmed tribal memory and honor codes. The artistic choices—depicting warriors with belts, knives, and facial hair—reflect the aesthetics of the time while helping modern researchers track stylistic shifts over centuries.

While stone statues and anthropomorphic monuments exist in many ancient cultures, what sets balbals apart is their symbolic connection across the Turkic world. From the Yenisei inscriptions in Siberia to grave fields in Anatolia, these statues share common themes: heroism, commemoration, and spirituality.

Türkiye’s own share of these heritage markers has gained renewed attention, particularly in the wake of increased cultural cooperation among Turkic nations. Recent archaeological discoveries in Eastern Anatolia have linked local stone figures to older traditions from Central Asia, suggesting a migration and evolution of artistic styles along the ancient Silk Road.

This rising interest in Turkic stone monuments isn’t just academic. Governments and cultural organizations across the region, including the Organization of Turkic States, are increasingly using archaeological heritage as a tool for soft power. Exhibitions, joint excavations, and research projects on balbals aim to strengthen cultural ties and highlight shared origins.

By revitalizing and reinterpreting these ancient markers, modern Turkic nations are reinforcing a collective identity rooted in common ancestry, mobility, and memory. Türkiye has taken a leading role in these initiatives, emphasizing the unifying symbolism of the balbals in shaping a pan-Turkic cultural narrative.

Despite their historical weight, many balbals remain vulnerable to erosion, theft, or neglect. Preservation efforts, including digital documentation and museum exhibitions, are now more vital than ever.