Long before reindeer and chimneys entered the story, the man who would inspire Santa Claus walked the marble-paved streets of Myra, a thriving Roman city on Türkiye's Mediterranean coast.

St. Nicholas was no mythical figure dwelling at the North Pole; he was a flesh-and-blood bishop who lived, served and died in what is now the coastal district of Demre in Antalya Province, leaving behind a legacy of generosity that would echo across continents and centuries.

Born around 270 C.E. in nearby Patara, one of the great cities of the ancient Lycian civilization, Nicholas grew up amid the grandeur of a prosperous trading port.

Patara boasted a 39-foot lighthouse, a 5,000-seat theater, and the bouleuterion, the parliament building of the Lycian League, considered the world's first democratic confederation.

This was no provincial backwater but a cosmopolitan hub connected by trade routes to Egypt and Rome, where the oracle of Apollo drew pilgrims second only to Delphi in fame.

Nicholas was raised in a well-off Christian family during an era when the faith remained illegal and marginalized across the Roman Empire. His parents died when he was young, leaving him in the care of an uncle believed to be a priest.

Tradition holds that the orphaned Nicholas distributed much of his inheritance to the poor, establishing early the pattern of anonymous charity that would define his life and, ultimately, his legend.

When the bishop of Myra died, the young Nicholas traveled from Patara to pay his respects. Local clergy debating a successor had received a dream that the new bishop would bear the name Nicholas. Upon the arrival of the young priest, they saw divine will fulfilled and appointed him to lead their community.

The position carried spiritual weight but modest worldly authority. As Dr. Adam English, author of The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus: The True Life and Trials of St. Nicholas of Myra, explains, the title at that time meant something akin to a head pastor, a very humble position with little formal power. Yet Nicholas's impact on his flock proved extraordinary.

The most famous story from Nicholas's time in Myra tells of a bankrupt merchant with three unmarried daughters. After selling all their possessions, the desperate father faced an unthinkable choice: his daughters might be forced into prostitution to survive. Nicholas heard of their plight and, under cover of darkness, walked to the merchant's house on three consecutive nights, throwing bags of gold coins through an open window. Each gift provided a dowry for one daughter, saving all three from ruin.

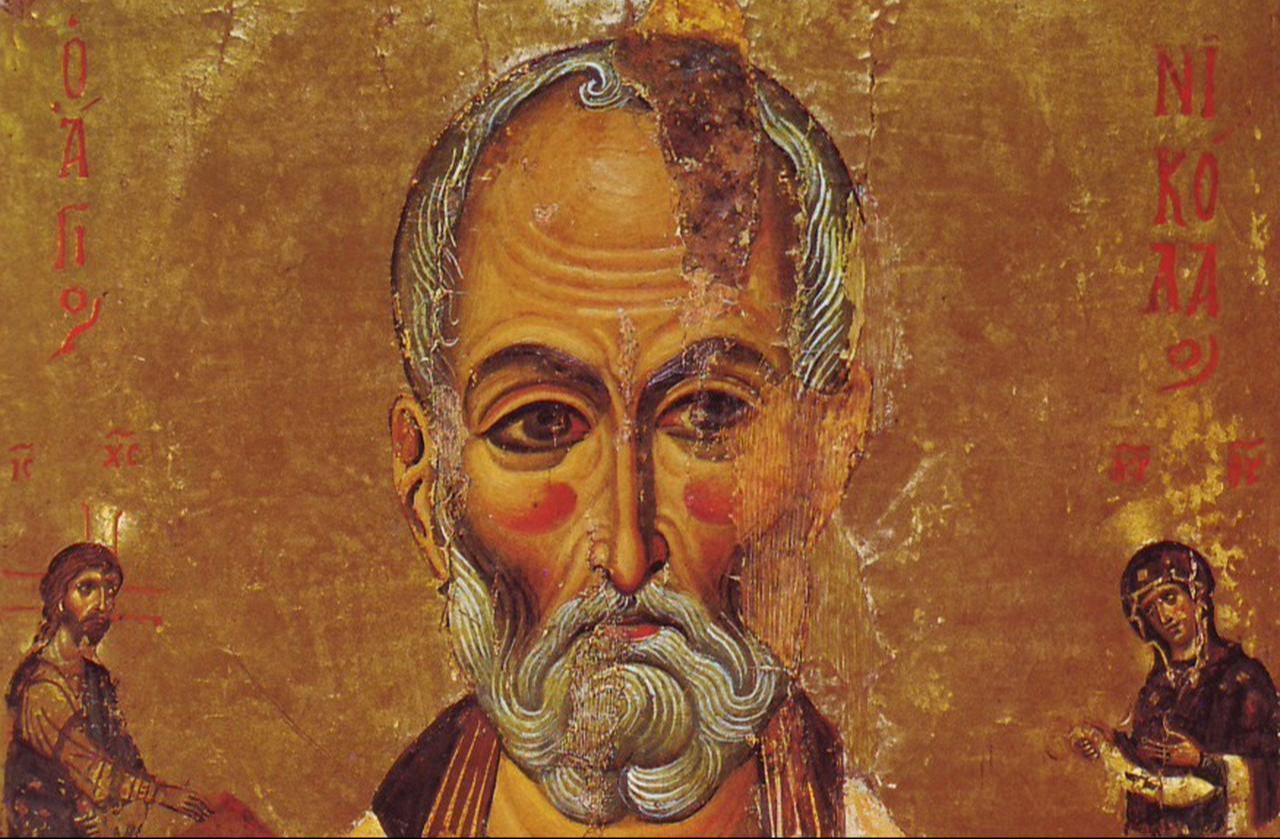

In some versions of the tale, Nicholas threw the gold down the chimney, and it landed in stockings hung by the fire to dry, a detail that would inspire a Christmas tradition recognized worldwide centuries later. Icons depicting St. Nicholas often show him holding three golden balls, a visual reference to this act of rescue.

The bishop's reputation for helping the poor, especially young women unable to marry due to a lack of dowries, spread throughout the region.

He was said to leave money secretly in homes at night to spare families the shame of accepting charity openly. His acts of generosity were always anonymous, always compassionate, and always aimed at preserving the dignity of those he helped.

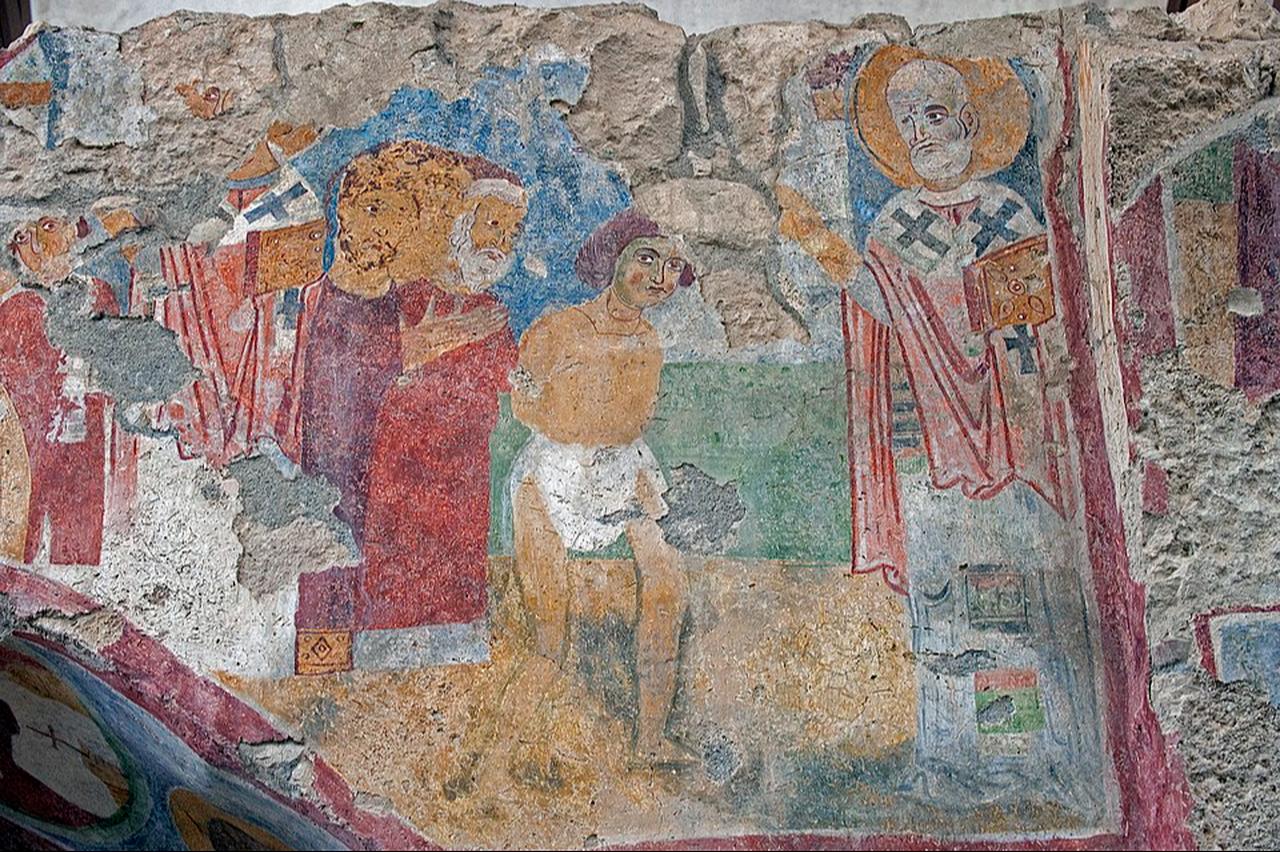

The church that bears Nicholas's name in modern Demre sits atop the foundations of the original fourth-century structure where he served. Built around 520, the current Byzantine building rises over layers of history. Archaeological excavations since 1989 have revealed the ancient floor level where Nicholas would have walked and prayed. A fresco showing Christ holding a Gospel book and making a gesture of blessing marks the area near where historical sources suggest the bishop's coffin was originally placed.

The church's design deliberately echoes the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, with an unfinished dome that remains incomplete even after a 19th-century restoration funded by Russian Emperor Alexander II. This architectural choice linked the Anatolian pilgrimage site to the holiest locations in Christianity, transforming Myra into a major destination for the faithful.

Today, the church stands dozens of feet below modern ground level, its walls adorned with mosaics and murals of saints. Multiple anchors appear throughout the iconography, a reference to Nicholas's role as patron saint of sailors, earned through legends of him calming storms at sea and protecting ships from disaster.

After Nicholas died around 350 C.E., his tomb in Myra's cathedral became a destination for pilgrims from across the Christian world. When Seljuk Turks conquered the region around 1085, Christians in Europe feared the saint's remains would be desecrated.

In 1087, sailors from Bari, Italy, broke into the church, smashed open the tomb, and seized most of the skeletal remains, sailing them back to their hometown. Venetian raiders arrived about a decade later to claim whatever fragments remained.

The theft sparked a centuries-long dispute over Nicholas's final resting place. Bari built a basilica to house its relics; Venice followed suit. Today, purported bone fragments rest in reliquaries across Europe, with a small collection preserved in Türkiye's Antalya Archaeological Museum.

Recent excavations at St. Nicholas Church have uncovered a limestone sarcophagus in a two-story annex, buried six meters deep and measuring approximately two meters in length. Researchers now await carbon testing results that may confirm whether any portion of the bishop's remains stayed in his beloved Myra.

The transformation of the Turkish bishop into Santa Claus unfolded gradually across continents and centuries. Nicholas became one of medieval Europe's most popular saints, with over 400 churches dedicated to him in England alone before the Reformation.

He was named patron saint of Greece, Russia, Sicily, numerous cities, and diverse groups, including sailors, newlyweds, children, pawnbrokers, and even thieves. The tradition of giving gifts on his feast day, Dec. 6, spread throughout Christian Europe.

Dutch settlers carried devotion to "Sint-Nicolaas" to America, where the name evolved into "Sinterklass" and eventually "Santa Claus." In 1823, New York professor Clement Clarke Moore published "A Visit from St. Nicholas," better known as "Twas the Night before Christmas," conjuring eight flying reindeer, a toy-filled sleigh, and a jolly, red-suited figure he described as "a right jolly old elf."

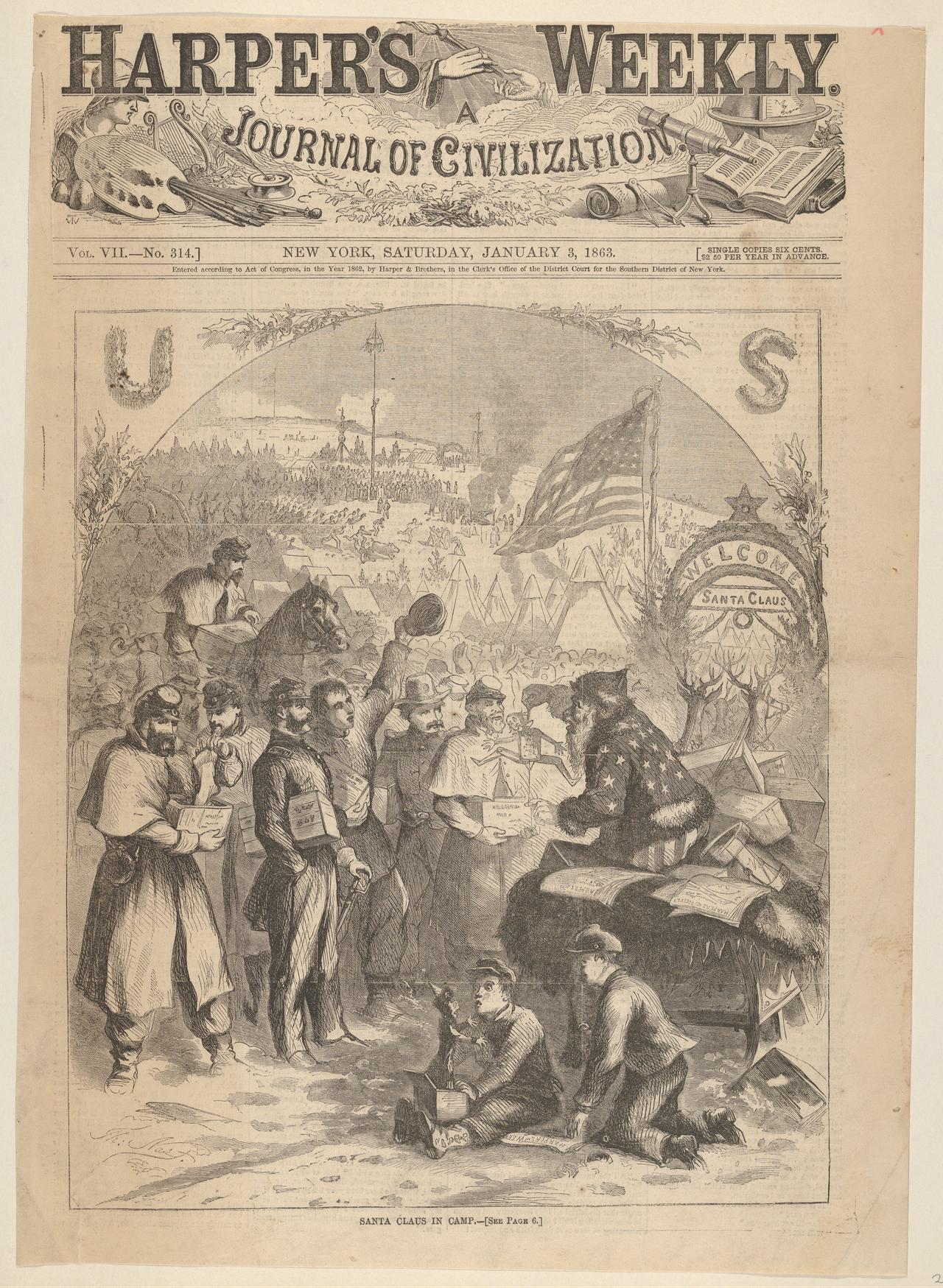

Illustrator Thomas Nast solidified the visual image in Harper's Weekly drawings between 1863 and 1866, commissioned by President Abraham Lincoln to boost Civil War troop morale. Swedish-American artist Haddon Sundblom refined the image further in 1924 Coca-Cola advertisements, creating the modern Santa recognized globally today.

Visitors to Türkiye's Mediterranean coast can still walk through the physical world Nicholas knew. Patara's sprawling archaeological site preserves the 5,000-seat theater, the bouleuterion where the Lycian League convened, and columns lining the ancient agora. Near the city's necropolis sits the Kaynak Church and cemetery, where scholars speculate the young Nicholas may have worshiped. The structure was built atop Christian burial sites dating to his era.

The journey continues 90 minutes southeast to Demre, where Nicholas spent most of his adult life. Just outside the town center rises a soaring rock-carved necropolis and Roman theater, testament to ancient Myra's prominence.

The St. Nicholas Memorial Museum—the formal name for the church—draws thousands of visitors annually, especially from Russia, where Orthodox devotion to the saint remains strong. The building was added to UNESCO's Tentative Heritage List in 2000, recognizing its significance as both a cultural treasure and a living pilgrimage site.

A statue of Nicholas with children stands outside the museum entrance, the latest in a series of contested monuments. As English notes, there have been three statues here over the years—a Coca-Cola Santa, a Russian bishop, and now a Turkish-looking man with children—because everyone wants to claim him as their own.

The Mediterranean cleric and the North Pole myth need not compete for cultural relevance.

Santa Claus can retain his department store throne, his flying reindeer, and his Christmas Eve magic—the delightful poem and commercial imagery that have brought joy to generations.

Meanwhile, St. Nicholas of Myra reclaims his rightful place in history: a fourth-century bishop who walked Türkiye's ancient streets, who gave away his wealth in secret, who defended the vulnerable and dignified the poor.

The archaeological work continuing beneath Demre's streets serves as a reminder that Santa Claus has roots—literal, physical roots in Turkish soil.

The limestone sarcophagus awaiting carbon testing, the ancient floor where Nicholas prayed, the church built over his tomb—these are not abstractions but tangible connections to a real man whose radical generosity inspired a legend that transcended geography, religion, and time itself.

Whether pilgrims come seeking a spiritual connection or travelers arrive curious about history, they find the same truth: the world's most famous gift-giver began his journey not at the North Pole, but on the sun-drenched shores of ancient Myra.