Türkiye has positioned itself as a global hotspot for archaeology, largely thanks to international attention on landmark projects such as Gobeklitepe and the wider Tas Tepeler (Stone Mounds) initiative. However, archaeologists, restorers, conservators, and museum professionals working in the country are facing severe structural challenges that threaten both scientific integrity and long-term preservation efforts. Many experts claim that projects promoted as investments in cultural heritage are in fact driven more by tourism than science.

One of the most pressing issues involves academic archaeologists, who are responsible not only for leading excavations but also for conducting the research behind them. According to a scholar who has directed excavations in Türkiye since the early 2000s, many digs are critically understaffed due to chronic underfunding. These shortages are worsened by increasing pressure from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism to complete projects on unrealistic timelines.

In more remote regions, the scarcity of archaeologists with academic credentials means that major excavation sites are often overseen by only one or two professionals. Despite the rise in archaeology departments across Turkish universities, many graduates lack field experience, resulting in underqualified archaeologists leading projects. Meanwhile, universities themselves struggle to allocate funds to research unless it serves narrowly defined institutional interests.

In reference to foreign-led excavations in Türkiye, one foreign academic said that Turkish co-directors—officially assigned to facilitate projects—are often more focused on supervision, which they described as “a practice that goes against scientific ethics.” They also noted the frustration foreign teams face when met with suspicion rather than cooperation.

Beyond institutional shortcomings, illegal treasure hunting remains a persistent threat. Known locally as "defineciler," these illicit diggers often target protected areas in search of gold or artifacts, damaging valuable heritage sites and disrupting ongoing scientific work. While law enforcement occasionally intervenes, archaeologists point out that enforcement is inconsistent, especially in rural areas where oversight is minimal.

Another growing concern is the spread of pseudoscientific content and conspiracy theories on social media and mainstream news platforms. These narratives not only misinform the public but also fuel distrust between local communities and archaeologists, particularly when excavations restrict access to lands with cultural or sentimental value. One academic emphasized the urgency of debunking such misleading reports, which are becoming increasingly common.

Restorers and conservators—experts responsible for preserving ancient structures and artifacts—face a different set of challenges. A senior academic working in a university’s restoration department noted that many skilled professionals are hired on temporary, project-based contracts with poor working conditions. In some cases, local municipalities and private contractors bypass professionals altogether, leading to failed restoration efforts.

These rushed or poorly managed restorations often involve repainting historical buildings inaccurately or using modern materials in ancient structures. Though visually appealing to tourists, such practices threaten the historical authenticity of heritage sites.

In June 2025, a group of conservator-restorers submitted a formal petition to the Turkish Parliament, calling for urgent reforms regarding employment rights and official recognition of their titles. They cited longstanding issues such as role ambiguity, lack of institutional acknowledgment, and unequal qualifications.

According to experts, Türkiye currently lacks a central authority capable of coordinating its archaeological and heritage policies effectively. Although the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums oversees many aspects of heritage management, even insiders admit that the agency is under-resourced and overstretched.

On-the-ground supervision is typically divided among various institutions, including universities, municipalities, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). This fragmented structure often leads to conflicting policies and duplicate efforts when different stakeholders launch projects without coordination.

Cultural heritage professionals interviewed by Türkiye Today collectively called for the creation of a national heritage council, composed of archaeologists, restorers, conservators, legal experts, and urban planners. Such a body, they argue, would help streamline decision-making and reduce conflicts of interest.

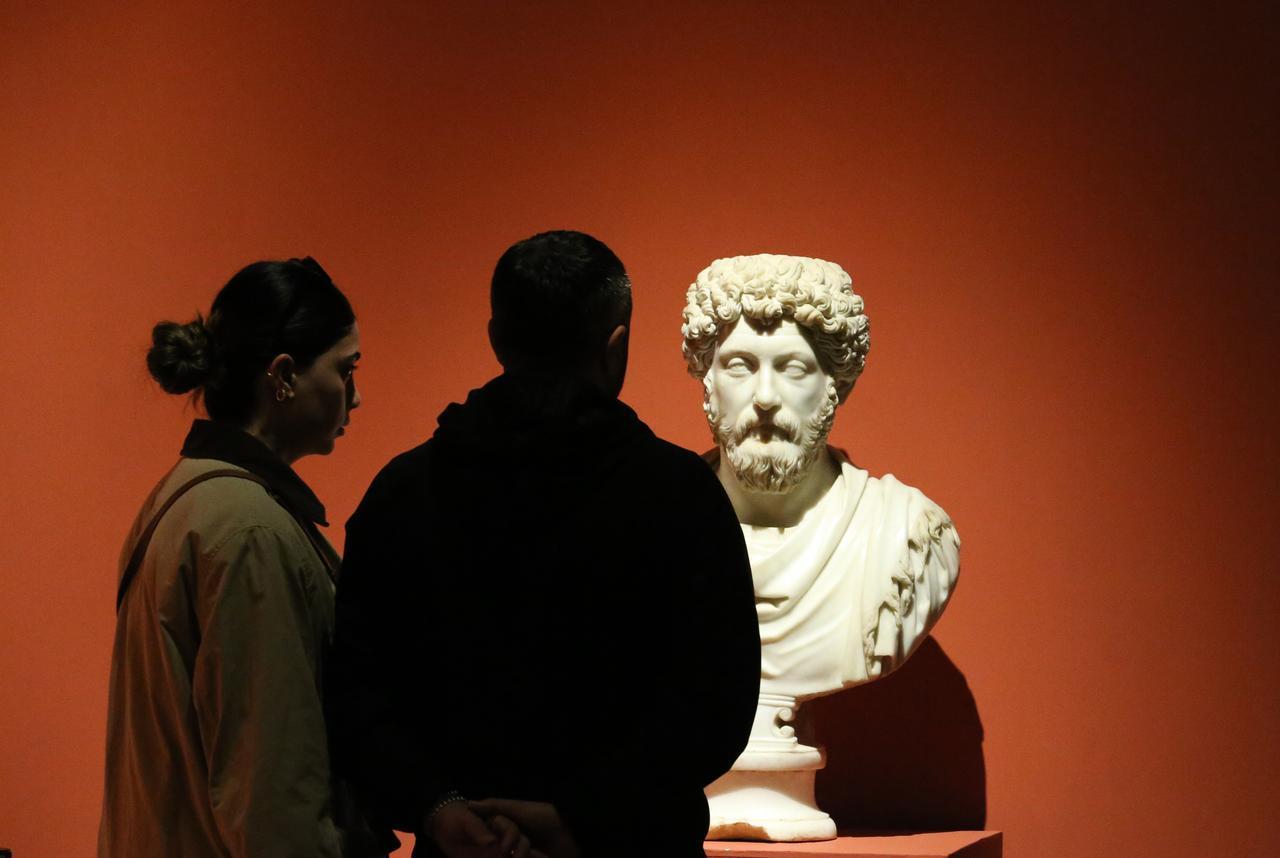

Museums across Türkiye, particularly those in regions with less tourist traffic, are also facing significant difficulties. Many lack qualified staff and rely heavily on short-term contracts. Opportunities for professional development are rare, and limited budgets prevent institutions from investing in modern display technologies or climate-controlled storage facilities.

These limitations hinder efforts to protect fragile artifacts and reduce the likelihood of international partnerships or traveling exhibitions. Without adequate funding, museums also struggle to develop educational programs or digital platforms that could engage the public more effectively.