A groundbreaking genetic analysis has revealed that the people who lived in the Eastern Alps during the Stone and Bronze Ages shared deep ancestral roots with early agricultural communities in Anatolia, the region that makes up much of present-day Türkiye. The findings shed new light on the genetic history of Otzi the Iceman and his surrounding communities, raising new questions about his unique lineage.

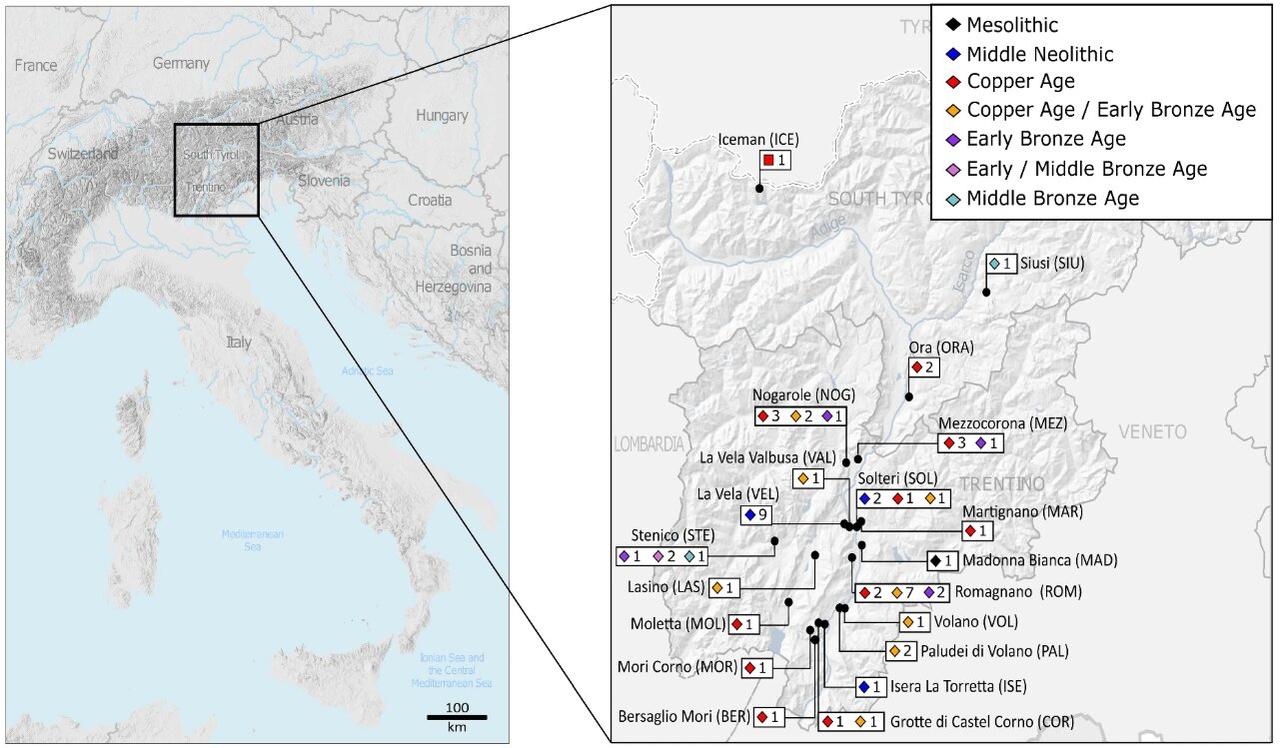

The research, published in Nature Communications, focused on the genetic material of 47 individuals who lived in the Austrian Tyrol between 6,400 B.C. and 1,300 B.C. Led by Valentina Coia and her team, the study aimed to explore the DNA of ancient Alpine populations in the area where Otzi’s well-preserved body was discovered in 1991.

By extracting DNA from bones and teeth, scientists uncovered that the majority of these ancient individuals derived between 80% and 90% of their ancestry from Neolithic Anatolian farmers. Remarkably, the genetic profile of this group remained largely unchanged for over two millennia, indicating a rare case of long-term genetic stability in contrast to the rest of prehistoric Europe, where frequent migrations reshaped populations over time.

Despite this shared background, Otzi’s genetic makeup showed some notable differences. While his overall ancestry linked him closely to Anatolian farmers like his neighbors, his Y-chromosome—which traces paternal lineage—revealed distinctions. The males in the study mostly shared ancestry common in ancient populations of what is now Germany and France, suggesting stable paternal lines. Otzi’s own paternal lineage, however, appeared more widespread and did not match the others examined.

Even more striking was Otzi’s maternal lineage, which scientists have yet to detect in any other ancient or modern DNA samples, including those analyzed in the current research. This raises intriguing possibilities. Could Otzi have belonged to a small, now-extinct group? Or does his unique heritage point to a form of social isolation or exile within early Alpine communities?

The study also pointed to gendered patterns of movement in these ancient societies. While male lineages appeared rooted in specific areas, the diversity of female ancestry suggested that women were more likely to move between communities, possibly joining their husbands’ groups after marriage—a social structure reflected in many early farming societies.

When researchers examined six of the best-preserved genomes, they found that these individuals, much like Otzi himself, had dark hair, brown eyes, and were lactose intolerant—a common trait before the widespread adoption of dairy consumption in Europe.

This latest research offers a new understanding of how ancient populations in the Alps were shaped by early Anatolian migration, yet managed to retain their genetic makeup over millennia. Although Otzi remains an anomaly, his story—and that of his neighbors—continues to provide valuable clues about prehistoric life in Europe. As Coia noted, “The Tyrolean Iceman was not an isolated case, but part of a broader pattern of genetic continuity in the Eastern Alps.”