In the late 19th century, long before official relations were established between Türkiye and Japan, one Japanese citizen stood out as a cultural bridge between the two nations.

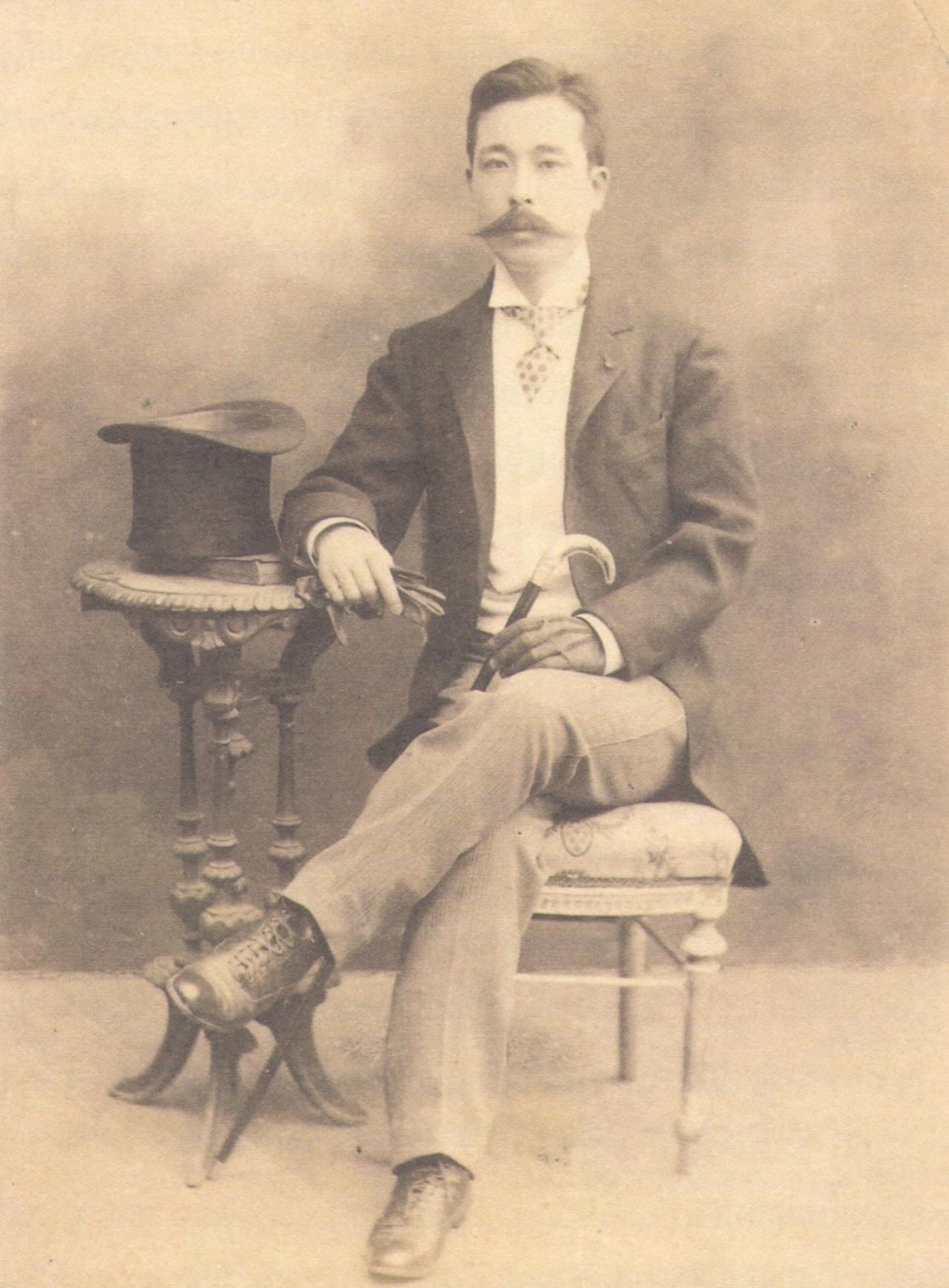

Yamada Torajiro, a merchant and intellectual who lived in Istanbul for nearly two decades, not only pursued a successful business career but also acted as a de facto honorary consul, helping Turkish–Japanese friendship flourish in its earliest days.

His writings about Türkiye—particularly those concerning the 1453 conquest of Istanbul—reveal both his personal admiration for the country and the influence of prevailing Western narratives of the time.

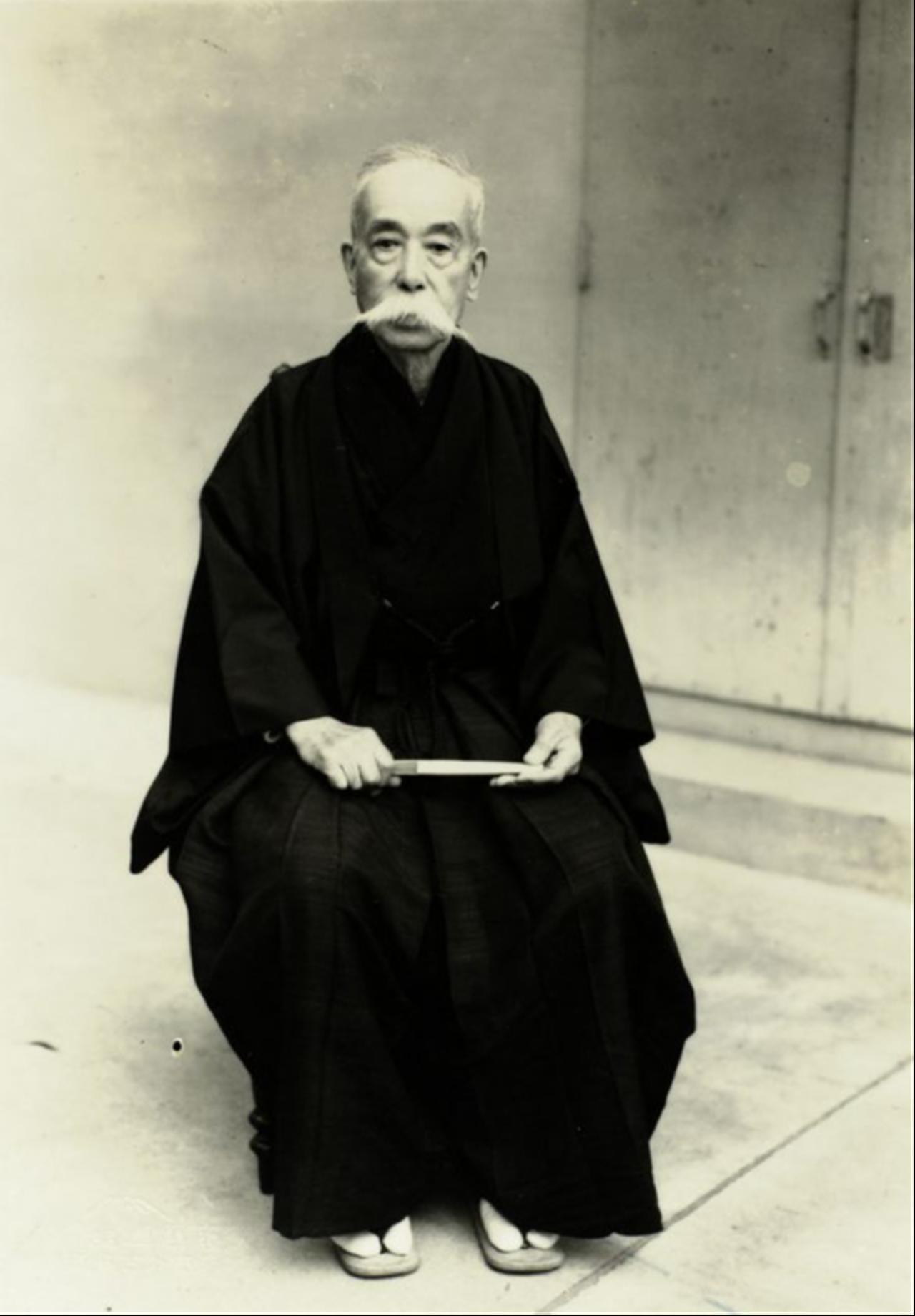

Born in 1866, Yamada was adopted by Yamada Soju, a master of the Sohenryu school of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Fluent in English, French, and German, he was part of Japan’s emerging intellectual elite. He arrived in Istanbul in 1892 and lived there until the outbreak of World War I.

Following the tragic Ertugrul Frigate disaster—a naval accident in which hundreds of Japanese sailors died off the coast of Wakayama—Yamada helped organize aid campaigns for the families of Turkish victims, earning widespread respect among Ottoman citizens.

During his years in Istanbul, he advised Sultan Abdulhamid II on Far Eastern porcelain and taught Japanese to Ottoman naval officers. His business ventures included the Nakamura Shoten (Nakamura Store) and later the Toyo Paper Manufacturing Company and the Japanese–Turkish Trade Association.

These enterprises reflected his role not only as a merchant but also as a cultural intermediary between two empires undergoing rapid modernization.

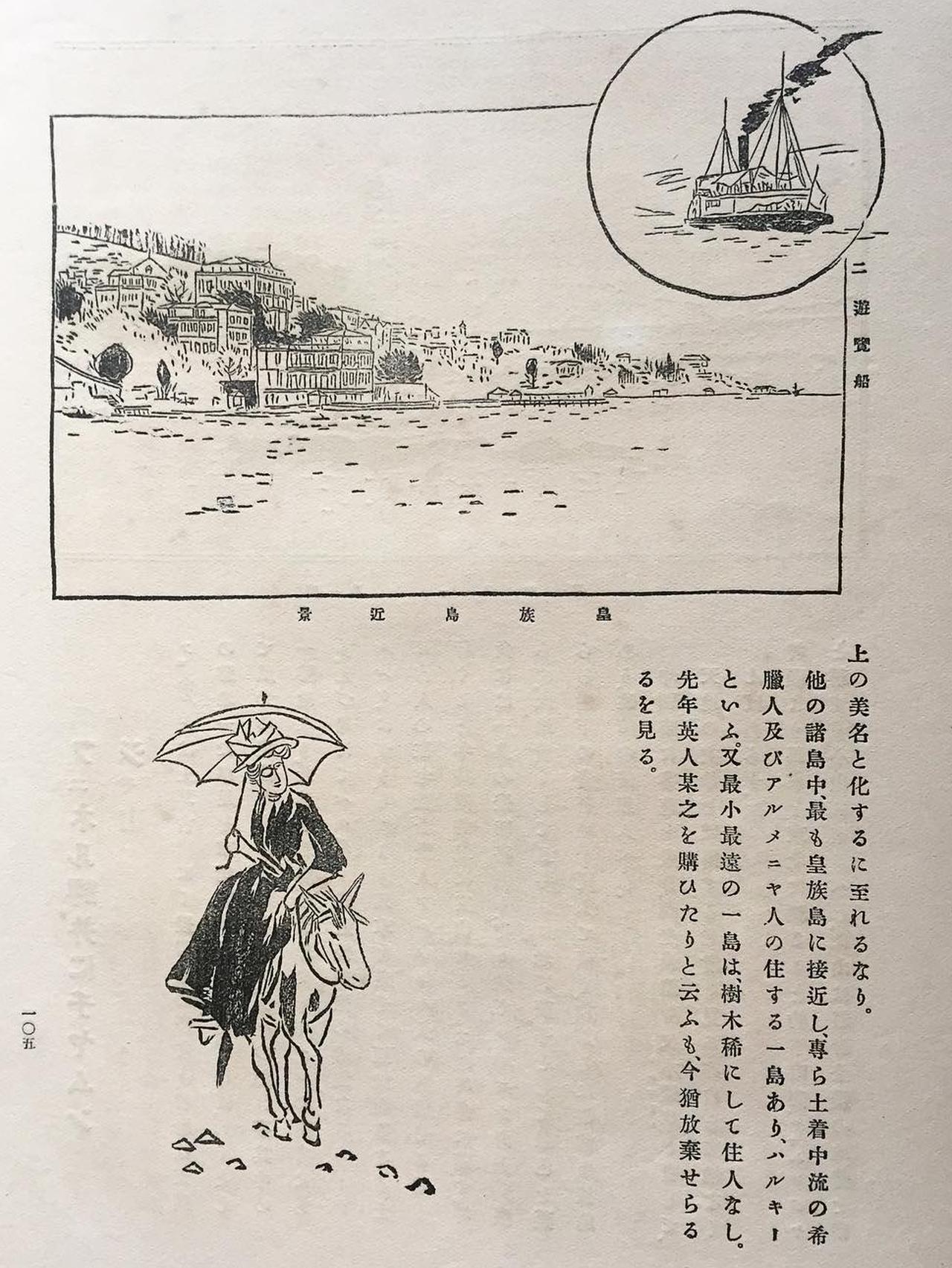

In his 1911 book Toruko Gakan (“A Pictorial Look at Turkey”) and articles for Taiyo magazine, Yamada portrayed 19th-century Istanbul as a cosmopolitan crossroads.

He described the famous Galata Bridge as “The Bridge of All Nations,” where Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Jews, and travelers from Asia, Africa, and Europe mingled daily.

He was particularly impressed by Istanbul’s openness to foreigners and its vibrant commercial life, where “most merchants were Greeks, Armenians, and Jews, while Turks were few in number.” Such observations offered a rare, first-hand Japanese perspective on Ottoman society’s multi-ethnic character.

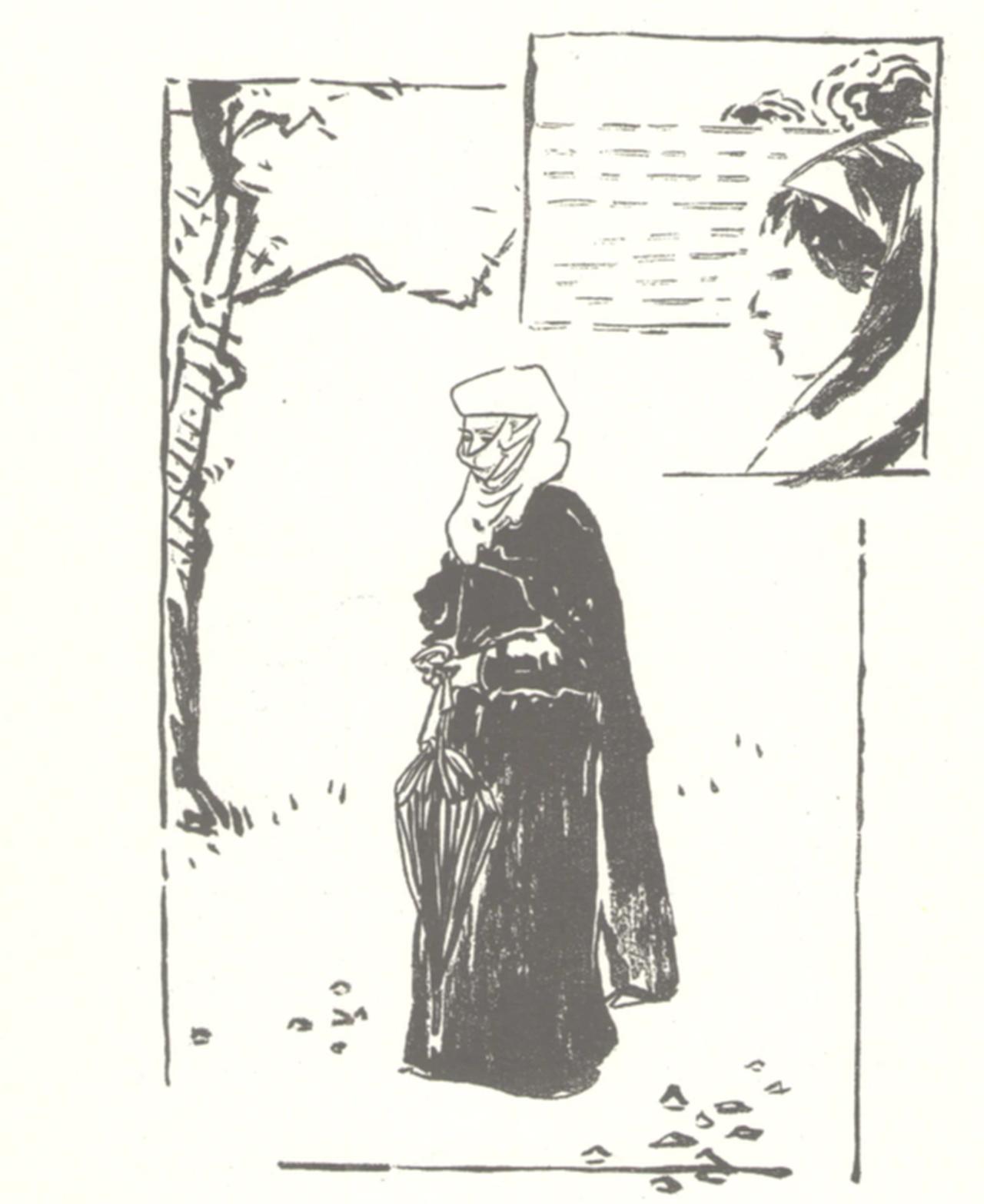

Unlike many European writers of his time who romanticized or misrepresented Ottoman women through the lens of Orientalism, Yamada’s tone was largely respectful, though shaped by his era’s social norms.

He noted that Turkish women did not sit with men and covered their faces after the age of twelve, comparing their modesty to that of women in China and Korea.

Yet he also observed that upper-class women were socially active and fluent in foreign languages such as French, English, and Greek.

“Those who think Turkish women are ignorant and thoughtless, no more than childbearing machines, are gravely mistaken,” he wrote, adding that their grace and skill in the arts equaled that of European women.

While Yamada’s writings about daily life in Türkiye reflected empathy and objectivity, his account of the 1453 conquest of Istanbul diverged sharply. In Toruko Gakan, he described Sultan Mehmed II leading “three hundred thousand soldiers” who “captured the city in one night,” depicting scenes of panic, destruction, and massacre inside Hagia Sophia.

His description—“ten thousand people turned into heaps of flesh and blood”—was emotionally charged and historically inaccurate, as even contemporary scholars noted that the city’s population was around 30,000 to 40,000 at the time.

Historians believe Yamada’s account was shaped by Western and local Greek sources rather than direct Ottoman archives. Notably, he omitted any mention of Sultan Mehmed’s decree guaranteeing the safety and freedom of the city’s Christian residents.

Later Japanese scholars, such as Horigawa Tooru in 2003, would correct this by highlighting Mehmed’s tolerance and protection of Byzantine citizens after the conquest.

The contrast between these two Japanese perspectives demonstrates how cultural interpretation evolves with time and context.

Yamada’s legacy endures as a symbol of early Türkiye–Japan cultural exchange. His writings—both insightful and flawed—reflect the complexities of viewing one civilization through the lens of another.

As Turkish historian Halil Inalcik once noted, “It is a mistake to generalize an entire nation.”

Yamada’s case stands as a historical reminder of that truth: even within one country, perspectives can differ widely depending on experience, empathy, and era.