Ancient Roman housing was never just about shelter ...

According to a recent academic study by senior archaeologist Orhan Baba, residential architecture in Rome actively reflected, reinforced, and even reshaped social hierarchy, turning homes into visible statements of class, wealth, and identity from the Republican era through the height of the empire.

Drawing on archaeological evidence from well-preserved cities such as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Ostia, alongside examples from Anatolia, including Ephesus and Zeugma in Türkiye, the research shows that Roman houses functioned as social instruments rather than neutral living spaces.

The study underlines that Roman houses should not be seen as passive reflections of social rank. Instead, they operated as spaces where status was constantly negotiated and displayed. Legal distinctions between patricians, plebeians, freed slaves, and enslaved people shaped access to land, safety, privacy, and decoration, all of which became embedded in residential design.

Three main housing types defined this system. The domus was a private townhouse associated with elite families, the villa extended elite lifestyles into rural and coastal settings, while the insula referred to multi-storey rental apartment blocks that accommodated the urban majority.

The domus, typically limited to one or two storeys, followed an inward-facing plan that restricted access from the street. This architectural choice was not accidental. It allowed homeowners, usually members of the upper classes, to control who could enter and how social interactions unfolded.

Central spaces such as the atrium and later the peristyle courtyard functioned as semi-public areas where guests were received. These rooms were carefully designed to put on display the household’s status, lineage, and cultural refinement, while private quarters remained hidden deeper inside the house. The layout itself reinforced social hierarchy by guiding movement through carefully staged spaces.

Villas expanded this logic into the countryside. Initially linked to agriculture, villas gradually took on a more luxurious character, especially during the Imperial period. Wealth generated through trade and expanded economic networks allowed elite families and newly enriched individuals to set up large estates that combined production with leisure.

Coastal villas, known as villa maritima, emphasized views, climate, and architectural sophistication rather than farming. The Villa of the Papyri near Herculaneum, with its vast size, multiple courtyards, library, and sculpture collection, is cited as a clear example of how architecture was used to project intellectual prestige alongside economic power.

At the other end of the spectrum stood the insula. These multistory apartment buildings rose rapidly in densely populated cities, especially Rome and Ostia, as land became scarce and urban populations grew. Built with cost efficiency in mind, insulae relied on Roman concrete and standardized layouts to maximize rental income.

Living conditions varied by floor, with lower levels often enjoying better access to water and decoration, while upper floors faced higher risks from fire and collapse. State regulations attempted to limit these dangers by imposing height restrictions and construction standards, yet the study notes that access to safety and legal protection remained uneven, reinforcing social inequality through architecture.

Beyond structure and layout, decoration played a central role in expressing status. Wall paintings, floor mosaics, sculptures, and furniture were chosen deliberately to communicate wealth and cultural literacy. Mythological scenes, rare pigments, and elaborate mosaics were especially common in elite homes, where they served as conversation pieces during social gatherings.

The research highlights that newly wealthy freed slaves often adopted and even exaggerated these decorative styles. The House of the Vettii in Pompeii, owned by two former slaves enriched through trade, is presented as a striking case where lavish imagery and dense iconography were used to assert social legitimacy and cultural belonging.

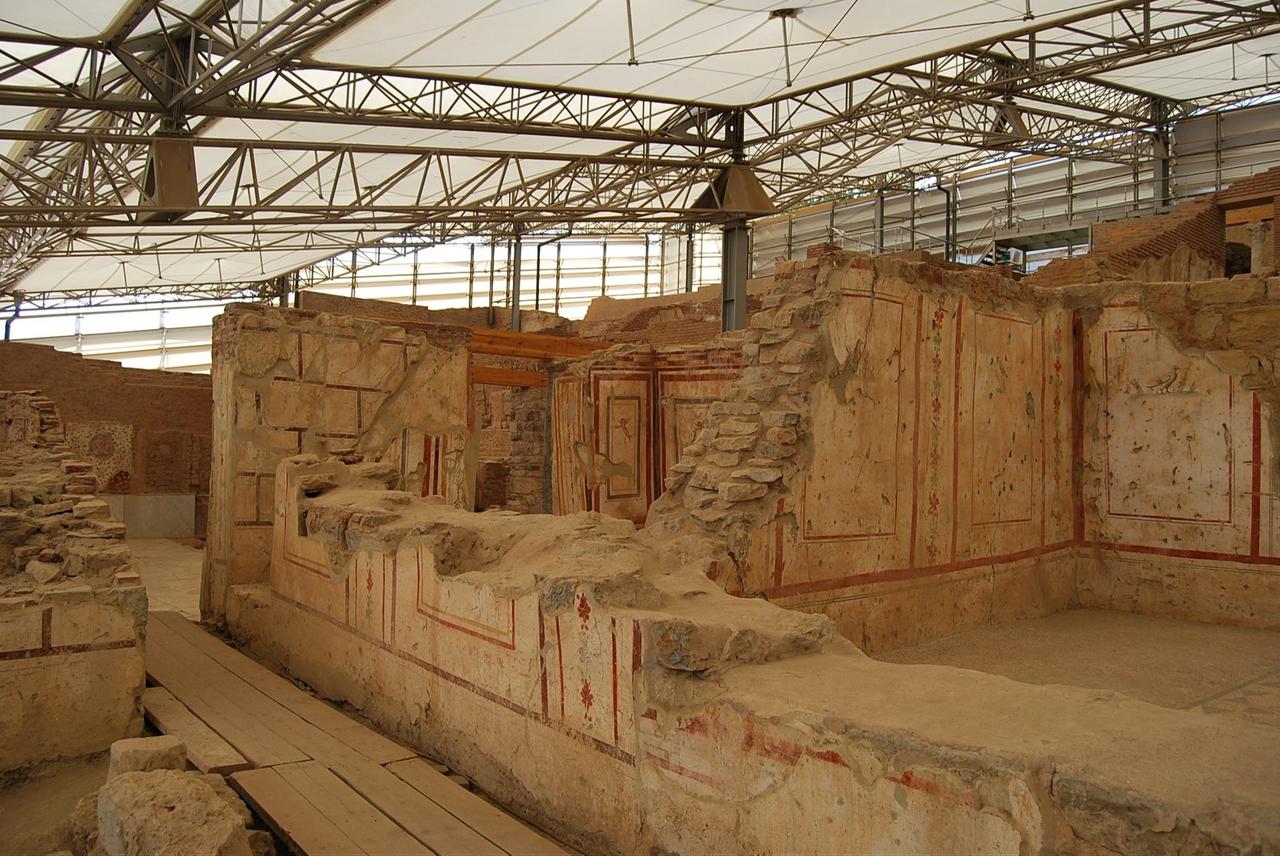

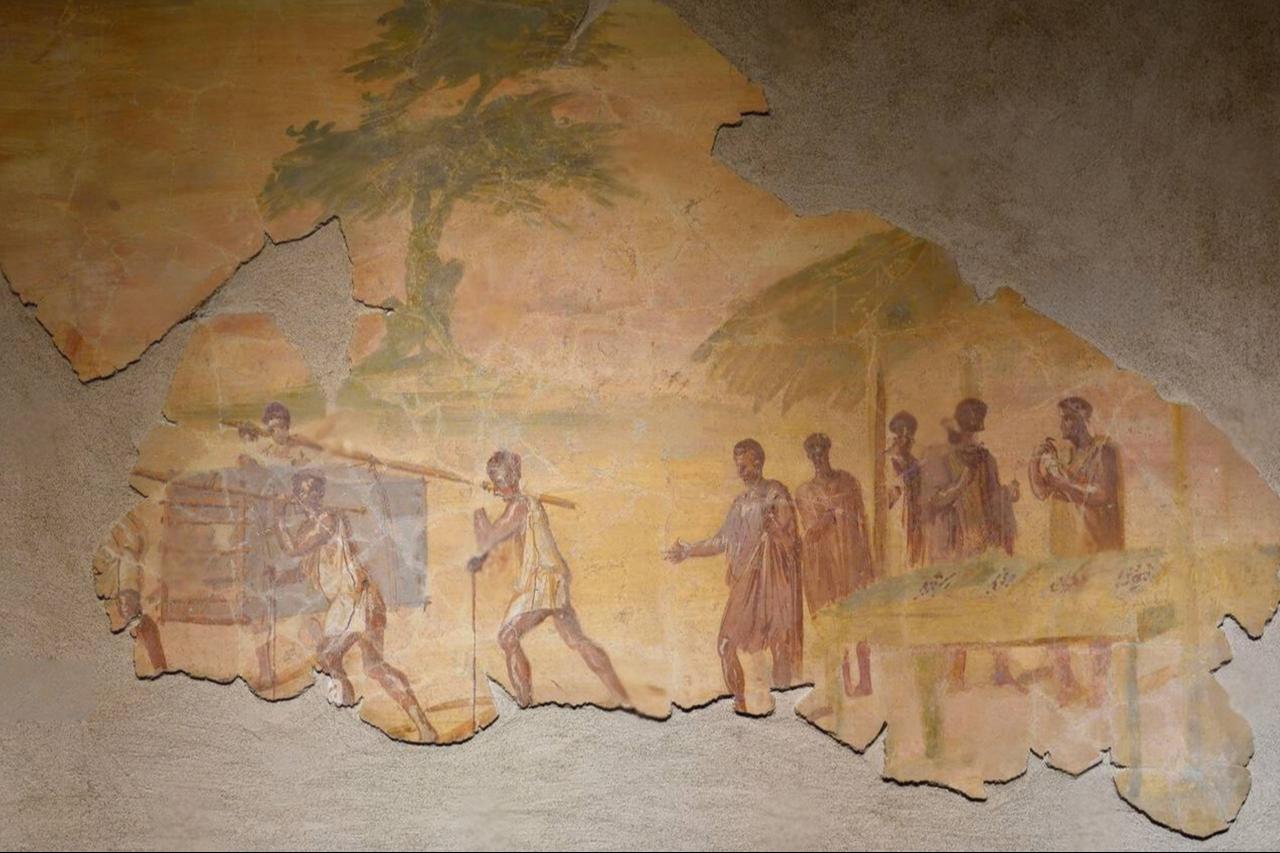

Evidence from Anatolia confirms that these patterns were not limited to Italy. In Ephesus, the so-called Terrace Houses display high-quality wall paintings and marble decoration comparable to those in central Roman cities. Similarly, the mosaic-rich houses of Zeugma reveal how local elites aligned themselves with Roman cultural norms while reinforcing their own regional authority.

These examples suggest that Roman residential architecture formed a shared visual language across the Empire, allowing elites to signal their place within a broader imperial hierarchy regardless of geography.

The study concludes that Roman houses embodied social distinctions as clearly as written laws or political institutions. Differences between domus, villa, and insula reflected not only comfort and aesthetics but also access to safety, privacy, and cultural representation.

Rather than silent ruins, Roman homes emerge as active participants in social life, shaping how identity, power, and inequality were experienced on a daily basis. By reading architecture alongside material culture, the research argues, ancient cities can be better understood as lived environments where class differences were constantly made visible.