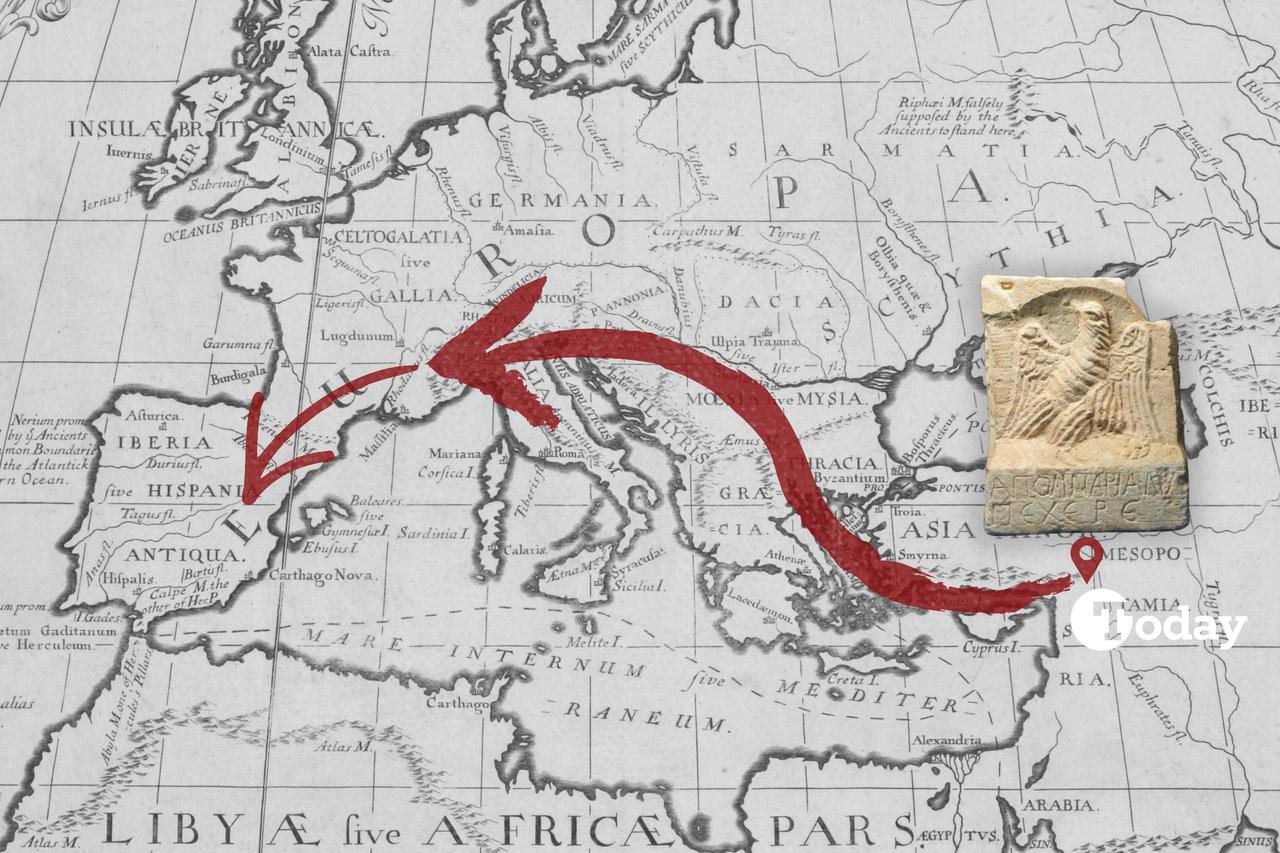

A funerary stele sold in France on April 11, 2024, and now owned by an antiquarian in Alicante, Spain, has been identified as originating from ancient Zeugma (Seleucia on the Euphrates) in southeastern Türkiye.

The study, prepared by Maria-Paz de Hoz from Complutense University of Madrid, traces the artifact’s craftsmanship and inscription to the city’s Roman-era necropoleis (burial grounds).

Carved from yellowish limestone and measuring roughly 55 x 45 x 20 centimeters, the piece combines a short Greek epitaph with a striking image of an eagle shown frontally with outstretched wings.

The two-line inscription reads “Apolinaris, free from sorrow, farewell,” using the standard funerary formula alype chaire that recurs on local grave markers. The text is cut in uneven letters—a sign of a non-professional hand—beneath a niche filled entirely by an eagle rendered with carefully marked wing and tail feathers.

Across roughly 70 known male stelae from Zeugma, the eagle appears as a near-fixed motif, while women’s stelae typically show a basket—often with wool—reflecting a gendered visual language in the city’s necropoleis (burial grounds). In some cases, the motif is replaced by a bust of the deceased, but the formulaic inscription remains.

Finds from multiple rock-cut cemeteries—comprising entrance galleries, arcosolia (arched recesses), and loculi (niches for coffins)—show that such stelae stood at tomb approaches or in front of burial recesses.

In several places around Zeugma, reliefs and inscriptions were carved directly on tomb walls; many are now submerged due to the Birecik Dam.

The formula alype chaire can be taken in two ways in the broader Syrian epigraphic habit: either wishing the deceased to be “free from sorrow” in the afterlife or praising a person “who did not cause grief” in life.

Zeugma’s texts accommodate both readings, and the paper notes parallels in neighboring cities that use similar consolatory farewells.

Interpretations of the eagle in northern Syria range from a protective emblem to a marker of male status and even a sign tied to local cults. In Zeugma’s setting—home to two Roman legions for much of the first–third centuries A.D.—the bird would have resonated with imperial power as well.

The study argues the motif likely identified the male deceased and symbolized his protection and continuation after death, while also acting as a civic identity marker distinctive to Zeugma.

The stele’s provenance records trace it from a French private collection to its 2024 sale in Saint-Cloud and its transfer to Spain. Stylistic and epigraphic parallels, however, leave little doubt about its origin in Roman Zeugma, when the city’s rock-cut cemeteries reached their artistic peak before the Sassanid invasion of 252/253 A.D.