A new study is reshaping our understanding of ancient Roman prosperity by arguing that the wealth of Pompeii, the iconic city frozen in time by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D., was largely built on the backs of enslaved laborers.

Despite widespread recognition of slavery’s presence in the Roman Empire, few historians have attempted to quantify its economic impact. In this groundbreaking paper published in Past & Present, a historian uses modern statistical techniques to estimate the economic contribution of enslaved laborers in Pompeii. The conclusion is striking: a significant share of the city’s wealth came directly from the labor of its enslaved population.

Pompeii is often hailed as a symbol of Roman prosperity—bustling with trade, adorned with elegant villas, and rich in urban culture. Yet this glittering surface concealed a darker reality: extensive exploitation.

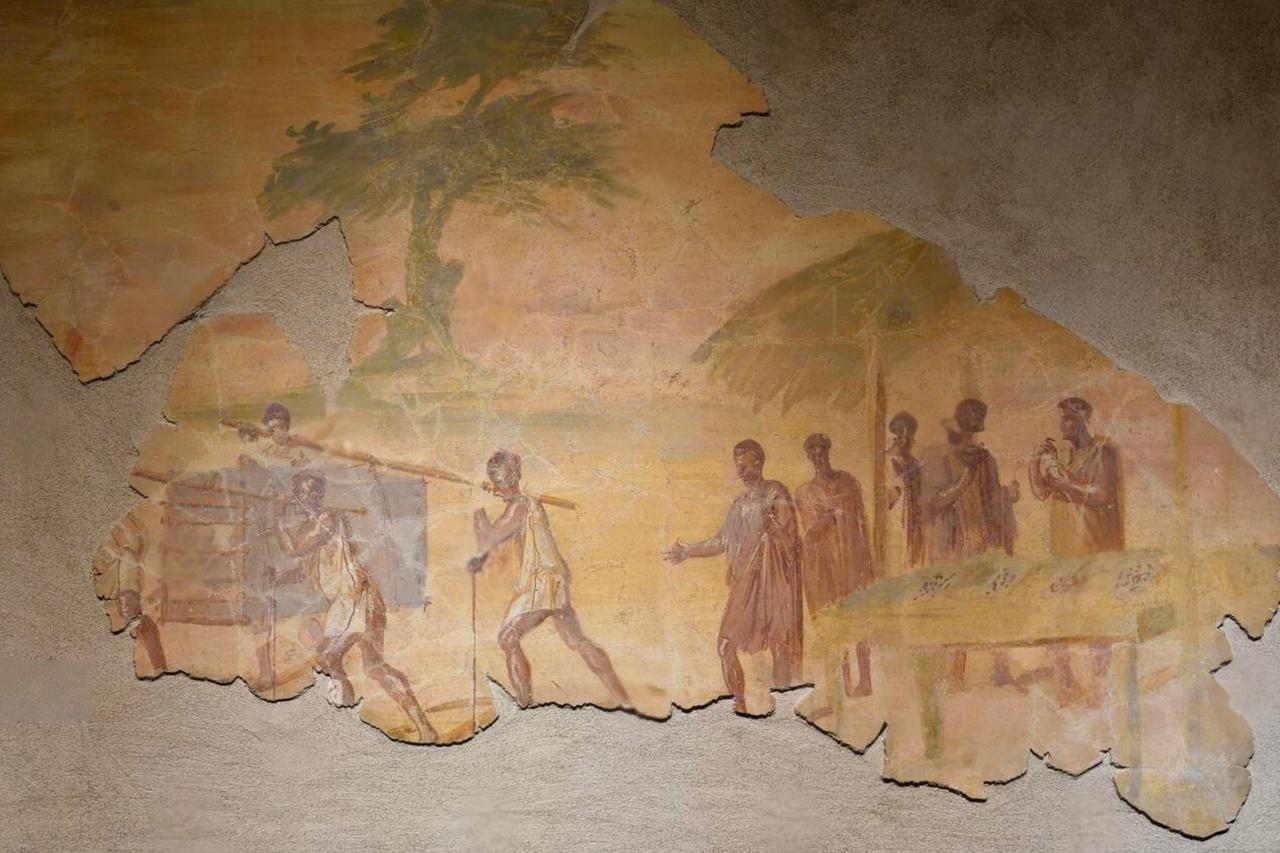

Recent archaeological discoveries, including confined workers’ quarters and bread ovens with barred windows, offer grim evidence of the labor conditions enslaved people endured. From prostitution to milling grain, enslaved individuals were central to economic production, but received none of its benefits.

To bridge the historical gap between prosperity and oppression, the study constructs a quantitative model based on ancient data: food prices, slave maintenance costs, slave productivity, and population demographics. Drawing on graffiti shopping lists, economic records, and comparative historical studies (including from the antebellum American South), the model simulates income generated by enslaved labor.

The findings suggest that enslaved individuals were not only widely present but highly productive, generating income on par with or even exceeding that of free laborers. Their maintenance costs were minimal, while their output fueled elite consumption and urban development.

The study criticizes mainstream Roman economic historiography for focusing heavily on trade, commerce, and institutional development, often overlooking labor. By reintroducing enslaved workers into the conversation, it challenges the prevailing “Smithian” view of Roman growth, which credits prosperity to free-market mechanisms under Pax Romana.

Instead, the research argues for a more labor-centered analysis, akin to debates on slavery’s role in the rise of capitalism in modern history, particularly in American and Caribbean contexts.

This fresh perspective holds profound implications: historians must incorporate the economic value of enslaved labor when assessing ancient urban economies like Pompeii. Also, this study ultimately invites scholars to treat ancient economies with the same critical tools used to study modern ones. In Pompeii, as in many other places across history, the glitter of prosperity was built on invisible chains.