The Ottoman court poet Baki stood before an impossible task in 1566: how to capture the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, the sultan who had expanded an empire and defined an era.

His solution—the Kanuni Mersiyesi (Elegy to Suleiman)—became the masterpiece of Ottoman elegiac poetry, beginning not with praise but with bewilderment: "O you trapped in the snare of fame and reputation, how long will you pursue the fleeting concerns of this transient world?" This wasn't ordinary sadness. It was bewilderment—a profound shock that refuses to accept death's finality even as faith demands submission to God's will.

The elegiac traditions of Ottoman Turkish (mersiye, meaning elegy) and Arabic poetry represent one of Islamic civilization's most emotionally rich literary achievements. These aren't merely poems about loss; they're theological wrestling matches, philosophical meditations, and sometimes bold political statements wrapped in beautiful verse. For over 14 centuries, Muslim poets have navigated the paradox at the heart of Islamic grief: how to mourn deeply while submitting to divine decree.

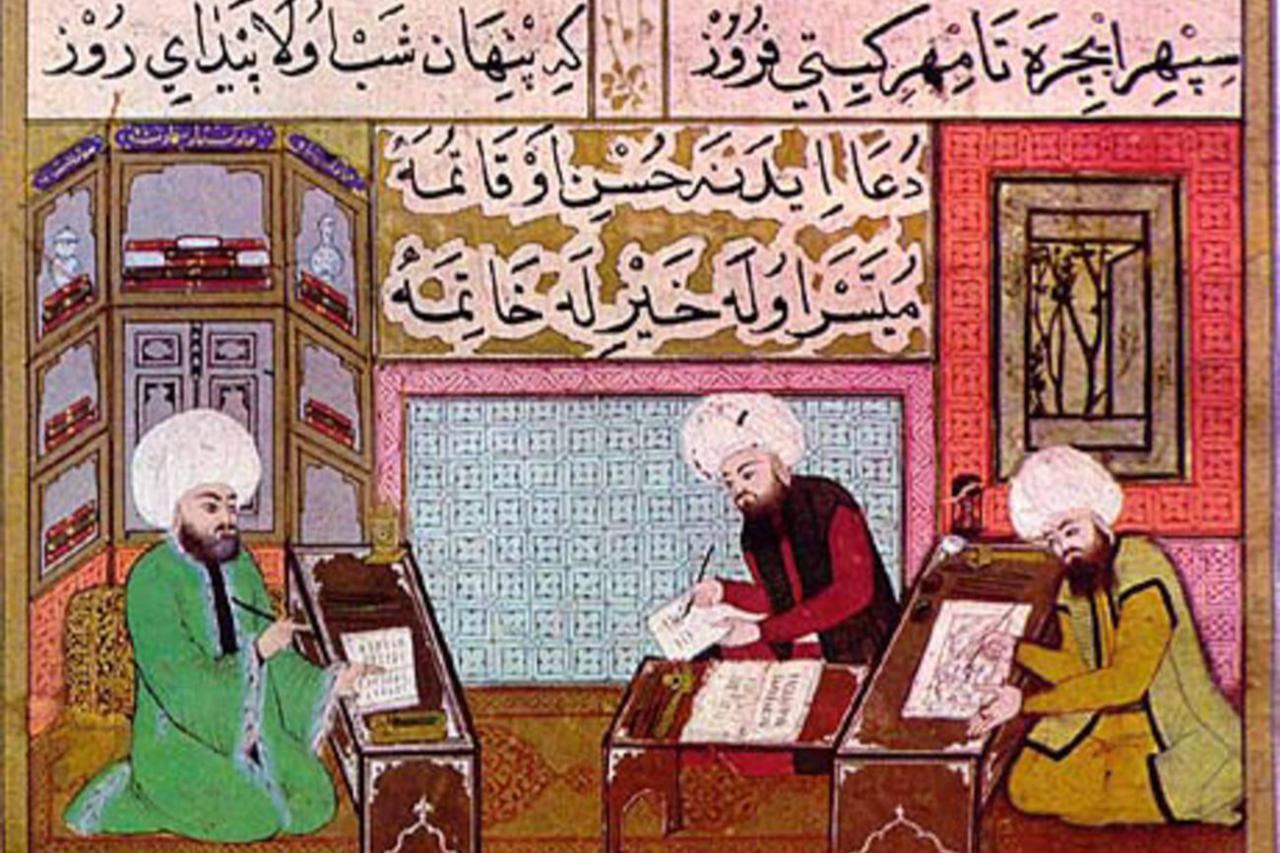

Ottoman Divan poetry elevated mersiye into high art through complex stanzaic forms called terkib-i bend and terci-i bend, where repeated refrains emphasized elaborate metaphors comparing the deceased to celestial bodies and exotic gardens.

The genre served multiple purposes—commemorating the dead, processing collective trauma, and occasionally critiquing power.

Baki's "Kanuni Mersiyesi" represents a peak for the form. When describing Suleiman's death, he wrote: "Our eyes may no longer see life and the world, what of it? His radiant face was the sun and moon to the world." The metaphor, beyond mere flattery, expressed that the universe's illumination had been extinguished by his loss.

Yet perhaps the boldest Ottoman mersiye came from Taslicali Yahya, the warrior-poet who dared elegize Sehzade Mustafa after Sultan Suleiman ordered his own son's execution in 1553.

His opening screamed: "Help! Help! One side of this world has collapsed / The brigands of death have taken away Mustafa Khan."

The poem spread among soldiers and commoners, inflaming public opinion against the grand vizier implicated in the prince's death. Here, the mersiye became dangerous—a coded political protest that could topple officials or end a poet's career. Yahya's poem made Mustafa the most elegized figure in Ottoman literature, with multiple poets, including the female poet Nisayi Hatun, adding their voices to this chorus of dissent.

The Sufi dimension emerged most powerfully in Seyh Galip's 1797 mersiye for his closest friend, the dervish Esrar Dede. His repeated refrain "aglasin" (let them weep) created a litany of grief: "Let my pearl-dropping eyes weep blood / Let them suddenly remember my faithful friend and weep." For Galip, a Mevlevi sheikh, the elegy expressed not just personal loss but the Sufi concept of separation from the beloved—both human and divine.

Fuzuli's monumental "Hadikatu's-Suada" (Garden of the Blessed), on the other hand, represents mersiye form's religious peak. His prose-poetry masterwork on Imam Hussain's martyrdom at Karbala became central to mourning traditions across the Muslim world, read annually during Muharram. Fuzuli wrote: "The lament expressing the memory of the Karbala incident is a heart-burning spark from the lightning of sorrow."

What distinguishes Islamic elegiac poetry is its focus on bewilderment and shock—rather than simple sorrow. In Sufi thought, bewilderment represents "a knowledge that enters a Sufi's heart without reflection," a state where human reason fails before God's infinite nature. When confronting death, poets don't just feel sad; they experience a kind of mental collapse, a paralyzing inability to accept that the deceased is truly gone.

This appears in elegies through what scholars call "the reproach motif"—poets daringly questioning divine will itself. Al-Sharif al-Murtada's elegy for Husayn demands: "How would God not hasten for their sakes, to cause the earth to heave, the sky to rain stones!" The formula "la tab'adan" (do not be gone) directly commands the dead not to depart, as if sheer poetic will could reverse death.

The difficulty of accepting death appears in elaborate metaphors. Ottoman and Arabic poets used celestial imagery (extinguished suns), natural disorder (blackened skies), and temporal confusion (using the present tense for historical deaths) to express how grief shatters normal reality. Death isn't accepted; it's protested through every literary device available.

Perhaps the most psychologically fascinating sub-genre is the Arabic ritha' an-nafs (self-elegy)—where poets facing certain death wrote their own epitaphs.

Malik ibn al-Rayb (d. 676 CE) composed the paradigmatic example. A reformed bandit converted to Islam, Malik fell fatally ill while returning from a war in Khorasan, dying alone in a desolate valley. His self-elegy has been studied for 14 centuries for its devastating intimacy:

"I remembered who would weep for me, but found

Only the sword and the Rudayni spear as mourners"

"My daughter says when she saw my departure approaching:

'This journey of yours will leave me fatherless!'"

"O my two companions, death draws near, so dismount

At a hillside, for I shall stay here for nights."

Malik's poem transforms "personal grief into universal philosophical statements on the futility of human existence," as one scholar notes. He mourns not just his death but his unfulfilled life—the family he'll never see again, the homeland he'll never reach, the heroic deeds left undone.

Imru' al-Qais, the legendary pre-Islamic poet and last king of Kinda, wrote his self-elegy after being poisoned by a Byzantine emperor. Seeing a woman's grave where he would die, he composed:

"My neighbor! We are both strangers here

And every stranger to a stranger is kin ...

Not strange is one whose home is distant

But strange is one whom dust has covered"

The true "strangeness" (ghurba, meaning alienation or exile) isn't geographical distance but death's ultimate separation.

These self-elegies reveal poets controlling their own narratives, achieving through verse the immortality denied by death. As modern Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish recognized by invoking Malik ibn al-Rayb, this tradition speaks across centuries to anyone confronting mortality under occupation, exile, or impending loss.

How do Islamic elegies balance raw human grief with theological submission to God's will? The answer lies in deep religious psychology. The Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) established that tears and heartbreak are legitimate—"Allah does not punish for the shedding of tears or the grief of the heart"—while excessive wailing that questions divine wisdom is prohibited. The Quranic model is Prophet Jacob (pbuh) mourning Joseph: "I complain of my anguish and sorrow only to Allah."

Ottoman and Arabic elegies create a ritual space where deep grief becomes an act of worship. The mourning assemblies (majlis) for Husayn, where Persian and Urdu marsiyas could extend beyond 200 stanzas, provided religiously approved outlets for communal weeping. The 6th Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq said upon hearing an elegy: "By God, the angels closest to God are witness here and they hear your words; they have wept as we have, and more."

The formula "inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un" (to God we belong and to Him we return) captures the paradox: acknowledging loss as returning a divine trust while feeling the full human weight of grief. Faith doesn't deny grief; it sanctifies it.

The mersiye tradition demonstrates how Islamic civilization integrated pre-Islamic Arabic and Persian forms with Islamic spiritual values, creating a rich literary culture that balanced orthodoxy with human emotional needs.

These poems save people from the isolation of grief, showing that for over a millennium, believers have walked this same razor's edge between devastation and faith, between bewilderment and submission, between commanding the dead not to leave and surrendering them to God's mercy.

In their beautiful verses, one finds not consolation but consecration, making the grief transformed into something beautiful, communal, and sacred.