Magic, particularly incantation rituals, was woven into the superstitious daily lives of people in ancient Anatolia, a recent study published in the Journal of Ege Social Sciences revealed.

Stretching from the Bronze Age Hittites to the Greco-Roman world, these practices—aimed at either bestowing blessings or invoking curses—were believed to offer solutions to everything from epidemics and infertility to love troubles and spiritual impurity.

The concept of afsunculuk, or incantation, in ancient Anatolian belief systems referred to ritual practices intended for the well-being of individuals or society. These spells were often intertwined with paganic religions and were performed by public figures. These practitioners believed in mana—a Melanesian term for a supernatural force—and saw illness as the result of a soul leaving the body or being invaded by another entity. Incantation was used to summon that soul back or to expel the invading force.

Such practices were not random or spontaneous; they followed codified rituals, often invoking divine favor through sacrifices, prayers, and symbolically charged materials such as cedar, iron, or animal parts.

In Hittite society, magical practices were divided into two categories: black magic, associated with curses and harm, and white magic, aimed at purification and healing. While harmful spells were outlawed and feared, protective rituals were officially sanctioned—even performed on behalf of kings and queens.

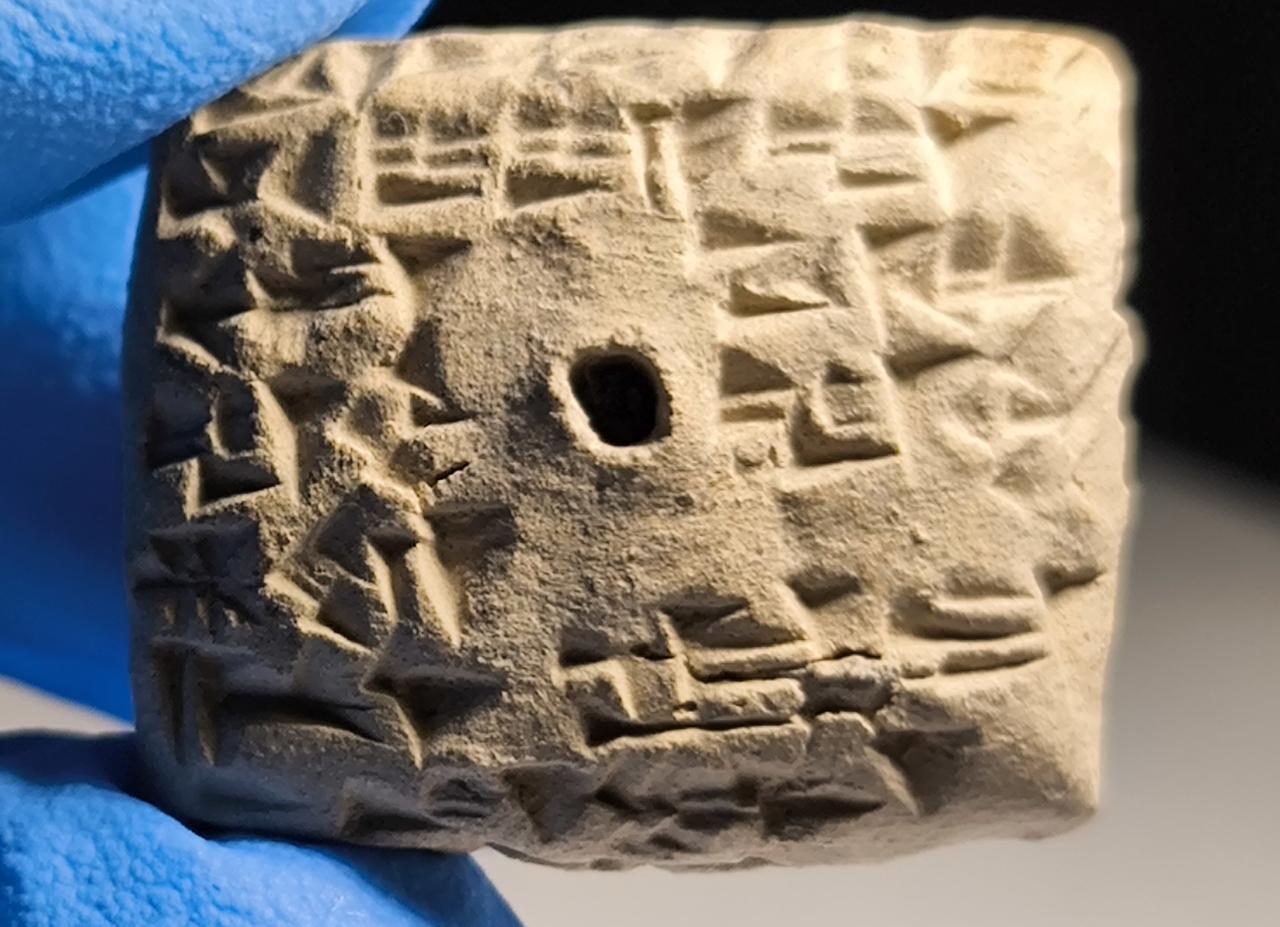

Texts found at the ancient capital of Hattusa reveal that thousands of ritual scripts focused on healing ailments like headaches, infertility, depression, or epidemics, as well as solving interpersonal conflicts and restoring social harmony. Named ritualists such as Ashella and Ammihatna developed detailed rites that could last several days and involved precise materials, spoken formulas, and actions meant to eliminate harmful forces.

Magic in ancient Greece and Rome retained many Anatolian influences but also developed distinct forms. While curses existed—especially through curse tablets and evil-eye protections—there was a stronger emphasis on personal well-being, love, and prophecy.

One of the most dramatic rituals was a love-binding spell performed by a woman named Simaitha, as recorded in a poem by Theocritus. By burning symbolic objects and invoking deities under the moonlight, she sought to rekindle a lover’s affection. The ritual used materials like laurel leaves, colored yarn, and mystical charms known as philtra.

In parallel, amulets known as gemmae—carved stones bearing magical symbols—were commonly worn as rings or pendants. These were believed to protect against diseases, enhance fertility, or ward off venomous creatures. Some depicted figures like Helios or Heracles; others bore animal motifs or encrypted spells.

Another crucial branch of ancient magic was divinatory incantation. Oracles, often affiliated with temples or royal courts, performed rituals to interpret signs from their gods through dreams, natural phenomena, or animal entrails.

Sacred sites like Delphi and Patara became centers for such oracles. In both Greek and Roman societies, prophecy informed not only personal choices but also state decisions, including warfare and succession.

The research underscores that magic in Anatolia was not seen merely as superstition—it was a complex system combining religion, medicine, performance, and philosophy. As such, the distinction between healing spells and harmful curses became clearer in Anatolia than in neighboring cultures like Egypt or Babylon.