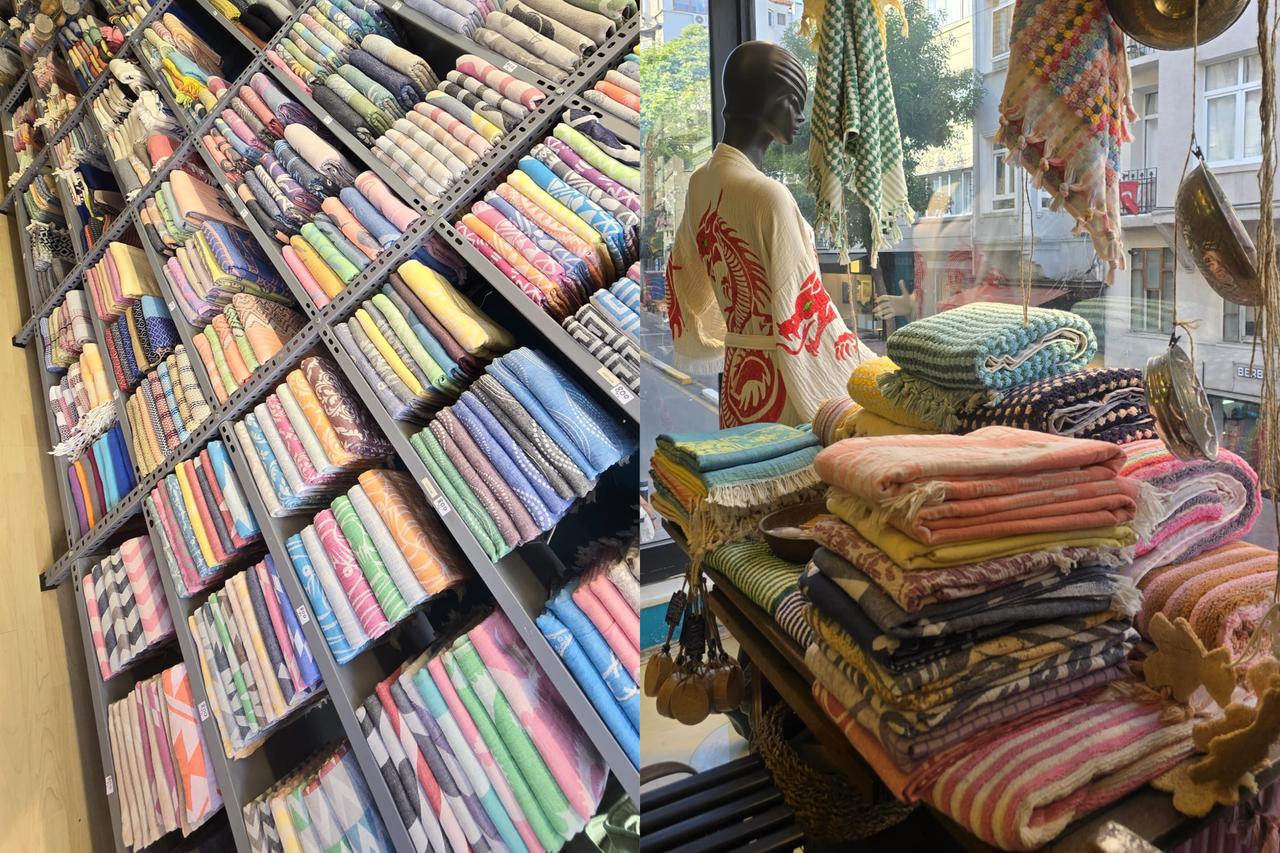

A wash of color hit me the moment I stepped into Dervis. Indigo, rose, terracotta and cream, towels were stacked floor-to-ceiling in quiet, rhythmic blocks. The room felt warm and full, but calm.

Inside the Beyoglu store, the towels rise in deliberate columns, their surfaces matte and dense. “When lifted, they carry real weight.” Nagehan Baysal Utkan, the co-owner of Dervis, told me. “Each one uses a full kilogram of yarn.”

The heft is immediate. It resists the lightness that has come to define so much mass production.

The co-owner traced the business back to her husband’s early years in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, where he began working at the age of 13 while still a student.

He first sold postcards, studying and working at the same time. Later, he became an antique carpet dealer, traveling across Anatolia and collecting textiles from different villages.

During those years, he began gathering old handwoven towels, some dating back nearly a century. Those pieces became the foundation of Dervis, which has now operated for three decades.

What began with four or five reproduced designs gradually expanded, though the production structure has remained largely unchanged.

Anatolia has long been a weaving region, with textile production shaping local economies and daily life for centuries. Dervis positions itself inside that continuum rather than outside it.

Families across Anatolia continue to weave towels by hand. In some villages, one person works the loom while another knots the fringes. A finished towel may travel to another city for stitching or pressing before reaching the store.

In one household, she said, five towels might be completed in a day. The pace is steady but limited by the capacity of hands and looms.

“It is not big money,” she said. “But you can survive.”

Cotton remains one of Türkiye’s most significant agricultural products, supporting hundreds of thousands of farming families and feeding a textile industry that represents a major share of national exports.

At Dervis, that larger system narrows to a single towel and a single kilogram of yarn.

The density distinguishes these towels from factory alternatives. Industrial production can stretch 1 kilogram of yarn into several thinner pieces designed to reduce cost and weight.

At Dervis, that same quantity becomes a single towel. The decision is practical, but it is also philosophical. Material is not treated as something to be extended as far as possible. It is used in full.

Cotton is sourced from southeastern Türkiye, and natural yarns are used.

Some motifs are integrated directly into the loom by adjusting its setup. Others are printed using hand-carved boxwood blocks already in the collection.

If a customer requests a new design that does not yet exist, a master carves a new block first, a process that can take a few days. The tools are simple, but the knowledge behind them is cumulative.

“We know the families,” she said. “We distribute the price equally.”

The model is intentionally small-scale. Some loom masters are in their eighties. One recently retired at 90 after teaching his children the craft. The system depends less on expansion than on continuity. Growth is not the central objective. Preservation is.

Before the pandemic, the business operated three stores, including one in the Grand Bazaar.

It has since consolidated into one Beyoglu location.

Most customers are international, and prices on the website are listed in dollars. Local buyers account for a small percentage of sales.

“They prefer machine-made,” she said. “Our designs do not change much. Only the colors.”

What caught my attention the most is that prices are fixed. There is no bargaining. The structure leaves little room for negotiation, but it also avoids the volatility that defines much of the surrounding market.

At the same time, terry cloth has reentered the global fashion conversation. Brands including Bottega Veneta, Prada and Loewe have incorporated towel-like textures into runway collections and accessories.

A fabric once associated primarily with bathrobes and beach resorts now appears in luxury ready-to-wear, reframed through cut, styling and price.

On the runway, terry cloth signals comfort rebranded as luxury. In Beyoglu, it remains part of a production chain shaped by manual labor and material limits.

The contrast is striking: what seems effortless in one setting often reflects sustained effort in another.

Dervis sells between 5,000 and 10,000 pieces annually. Rising costs and currency fluctuations have narrowed margins.

Yarn suppliers no longer keep extensive color stock, and orders must be placed months in advance. Small production does not shield a business from global pressures. It simply makes those pressures more immediate.

Imitations appear in nearby shops at lower prices, often made from synthetic blends that mimic the surface but not the weight. “Not everyone can see the difference,” she said. “Quality is more important than quantity.”

Inside Dervis, the towels remain stacked, dense and largely unchanged. Trends move quickly. While a kilogram of cotton, woven slowly, does not.