A research team has reconstructed the gut microbiome of a young man who lived roughly 1,000 years ago in what is now Mexico—offering a unique glimpse into pre-Hispanic diet and health.

The study, published in PLOS One, analyzed preserved intestinal tissue and a coprolite (archaeological term for fossilized feces) recovered from a dry cave near Zimapan.

Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the team identified the bacterial community that once thrived inside the man’s gut.

In this exclusive interview with Türkiye Today, study co-author Rene Cerritos of the Intersecretarial Commission on Biosafety and Genetically Modified Organisms discussed the findings, including what the team believes might be an ancestral link between ancient and modern gut bacteria.

The study identified bacterial families typical of the human gut, such as Peptostreptococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterococcaceae, with unusually high levels of Clostridiaceae. These groups help break down complex plant materials.

Türkiye Today asked about evidence of insect consumption, and Cerritos explained that several Clostridium species can degrade chitin, the hard structural material in insects.

“Although we have not yet detected the genes that give rise to chitinases, we speculate that insect consumption was likely,” he said, pointing to records showing 99 edible insect species in the region.

“We also found bacteria from the Lachnospiraceae family that can break down complex polysaccharides like cellulose or lignin—turning them into short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate.”

Cerritos added that future research aims to identify the specific genes responsible for these functions.

One of the most intriguing findings was the detection of Romboutsia hominis, a species known in modern humans but never before identified in ancient remains.

When Türkiye Today asked about the risk of modern contamination, Cerritos said that the genus Romboutsia is phylogenetically close to Clostridium, with species inhabiting soil and animal intestines.

“Using the technique applied in this study, the most similar sequences in databases corresponded to Romboutsia hominis,” he explained.

“More detailed work is needed to confirm that our sequence is almost identical to the modern bacterium described over five years ago.”

He added that the variant detected in Zimapan is probably not identical to today’s version: “Since 1,000 years have passed, the R. hominis variant we found is likely different. We may be seeing the ancestor of current bacteria. Rather than contamination, we could be facing bacteria that have coexisted with humans for thousands of years, as long as we do not change our diets.”

Cerritos warned that modern Western diets are drastically altering this delicate microbial balance.

The Türkiye Today interview also explored how the mummy’s tissues survived so long. Cerritos attributed this to both natural and cultural factors. “Several environmental conditions influenced the preservation,” he said.

The cave lies on the slope of a cliff, making it difficult for animals or humans to access, while the region’s xerophilous scrub vegetation keeps humidity extremely low.

The body—referred to by the research team as Hna Hnu, an ancient Otomi name—was wrapped in a mortuary bundle, a tightly woven funerary package made of maguey fiber cords, cotton and jute walls.

“Hna Hnu was imprisoned for 1,000 years within those cotton and jute walls tied with maguey fiber cords,” Cerritos said.

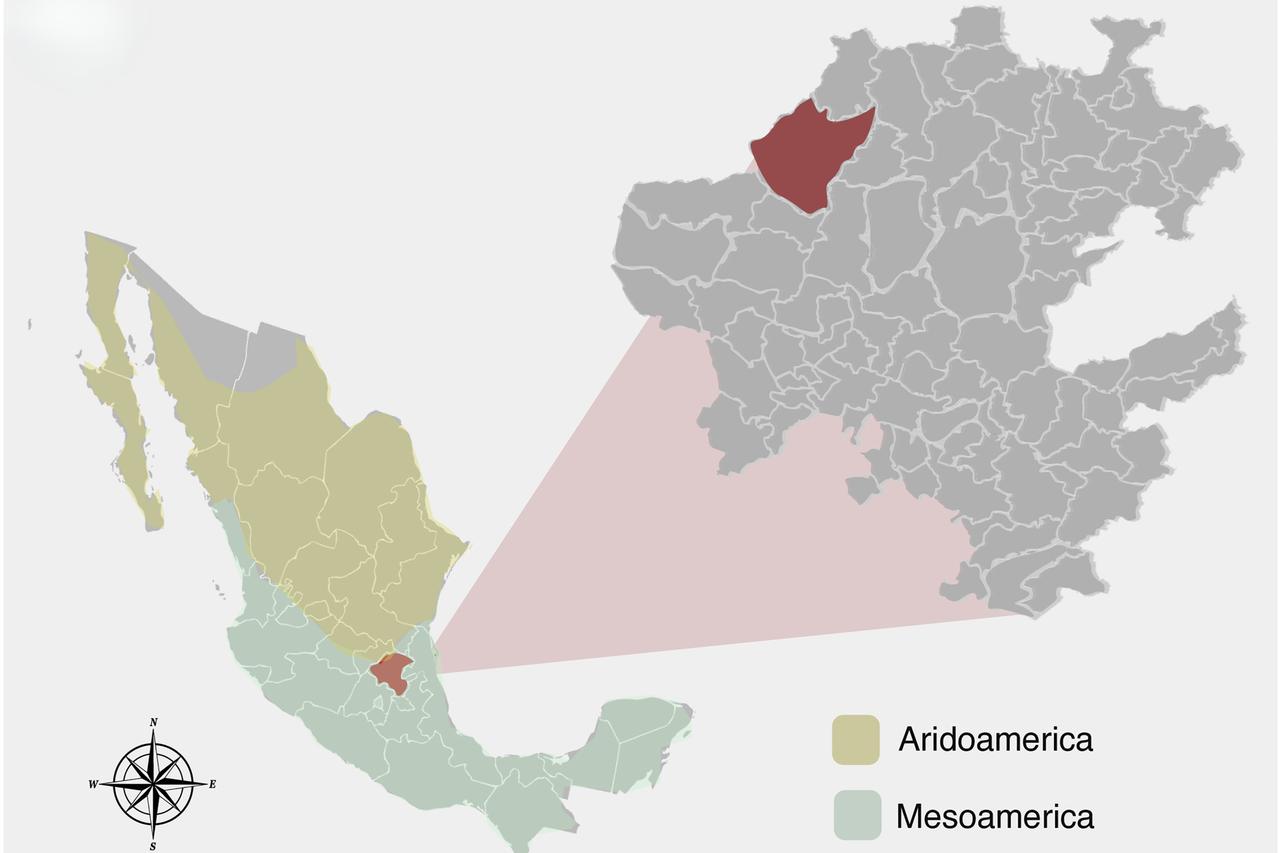

Previous analyses suggest that Hna Hnu was a 21–35-year-old seasonal, seminomadic hunter-gatherer from the Otopame culture, part of the ancient Mesoamerican world. His body was placed inside a cave that acted as a natural vault. Beneath an outer maguey mat lay a woven sheet of native brown cotton.

As the authors wrote in PLOS One: “The Zimapan man’s remains were neatly wrapped like a bundle… Studying the mathematical composition of the knots within the fabric, we concluded that it was a peculiar and complex arrangement to carry out.”

The burial’s careful construction suggests that Hna Hnu may have held significance in his community.

The reconstruction of Hna Hnu’s gut joins a growing list of ancient microbiome studies, including work on the Tyrolean Iceman and mummies from Andean civilizations.

According to Cerritos, the next step is to sequence environmental DNA to map bacterial genomes and determine their functions.

“The Zimapan man, or Hna Hnu as we affectionately call him, holds many secrets that we will gradually uncover,” he told Türkiye Today.

“We still don’t know what caused such a young man to die, nor whether he carried any genetic traits for congenital disease. We hope to soon answer these questions.”