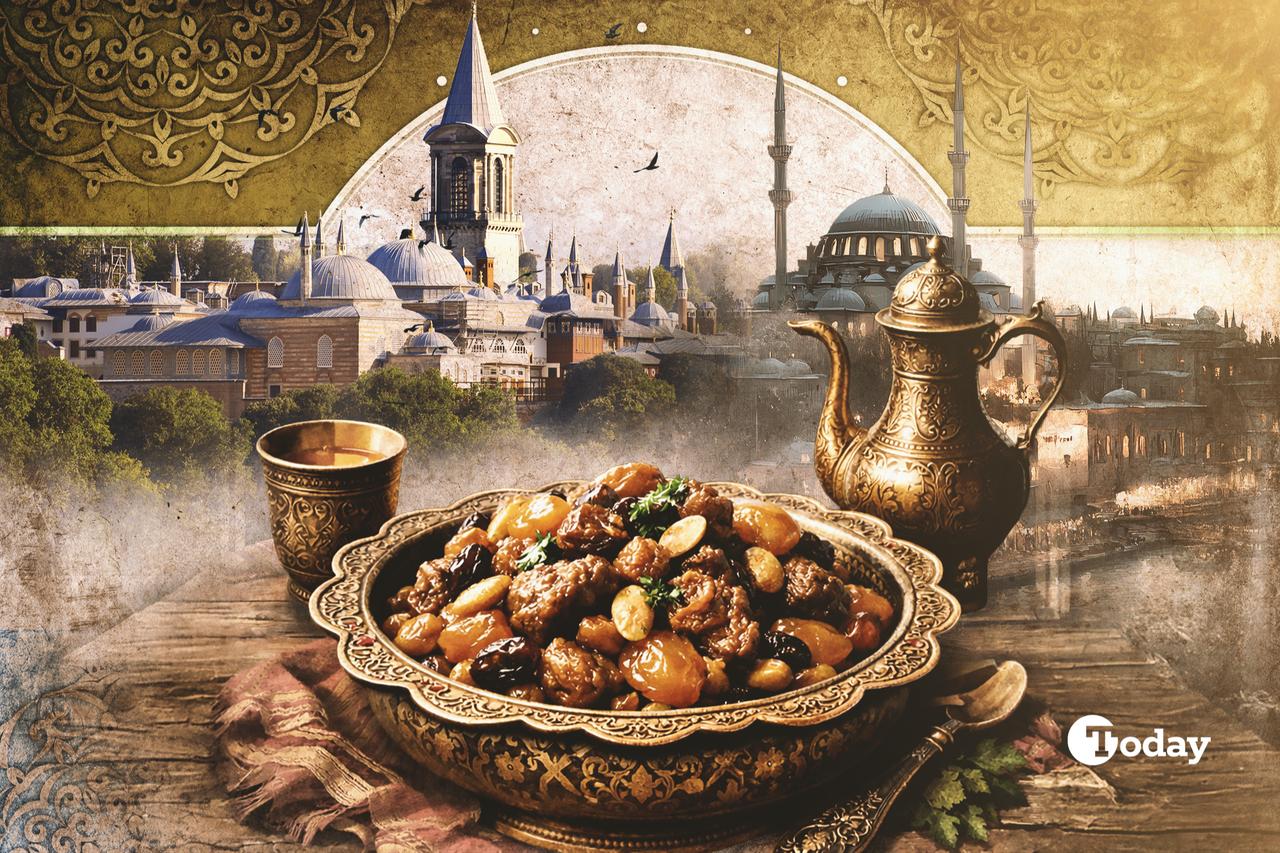

Mutancana arrives at the table looking like Christmas stuffing that has staged a successful coup against the pantry. The platter of celebratory eats is impossible to look at without understanding that it has declared itself the main dish, with all the delicacy of an exploding grenade.

Lamb, apricots, raisins, almonds, honey and cinnamon burst their boundaries, attacking the senses with the smell of seasonal confusion. Whether it is dinner or dessert is beside the point; mutancana is clearly not something that wishes to apologize.

Mutancana is no mild-mannered mutton. It calmly annexes the table with the confidence of a liturgical calendar—something that predates every diner’s categories and fully expects to outlive them.

The dish is naturally introduced with a flourish. It was, of course, “Mehmed the Conqueror’s Favorite.” The promotional plug appears everywhere it might be commercially useful: menus, guidebooks, heritage brochures, palace-adjacent websites. The pitch is thrown with the serene confidence of a fact that has never once been checked.

There’s no evidence to prove Mehmed II loved mutancana. None. No diary entry. No court chronicle. No marginal note in a kitchen ledger reading “the padisah requested seconds.”

The only certainty: mutancana is old, very old. This meaty plate and its attendant extravagances were codified in the 15th-century Ottoman palace kitchens. Modern diners want proximity; they want to imagine the conqueror munching thoughtfully while planning his next campaign. If hunger is the best sauce, as Cicero claimed, egotism is at least a generous sprinkling of MSG.

This is how dishes acquire owners. History, left to itself, is terrible at marketing. Recipes survive badly: fragmented, unattributed, stripped of personality. To make them shine, they are assigned a face, and preferably a powerful one. Mehmed II is ideal casting: young, victorious, Renaissance-adjacent, and already surrounded by anecdotes involving maps, painters, cannons, and ambition. If you were inventing a sultan to sell a dish product, he is exactly the figure you’d conjure.

Culinary history is full of these compressions. Marie-Antoinette never said, “Let them eat cake.” Marco Polo never brought pasta to Italy and Bismarck rarely had 16 eggs for breakfast. Food rumors endure because they make history chewable. They reduce systems and long trends to single gestures. A dish gains authority when a face can be stapled to it and the paperwork quietly binned.

To be sure, mutancana feels like something a sultan ought to have eaten. It's why the gossip sticks. The dish looks imperial: rich but disciplined, sweet but controlled—luxury-coded, sans vulgarity. What this aesthetic plausibility conceals is how palace kitchens actually worked.

The imperial kitchens of Istanbul were not theaters of whimsy or personal indulgence. They were bureaucratic machines. The Matbah-i Amire functioned like a ministry. At its head stood the ascibasi, the chief cook. Beneath him worked ranked ustas and kalfas, each responsible for specific preparations. Stores were overseen by the kilercibasi. Sweets, syrups and medicinal pastes emerged from the helvahane, a unit that resembles a pharmaceutical wing more than a pastry kitchen.

This was a system organized around repeatability rather than favorites. Palace food was meant to taste the same regardless of mood, season, or supply shock. A dish that could absorb variation without collapsing was prized.

Mutancana emerges as the champion. Dried fruit travels; honey keeps; cinnamon smooths irregularities; lamb forgives; and rice doesn’t complain. This is not decadence; it is logistics with manners.

The Byzantines understood this long before the Ottomans. Late Roman and Byzantine cooks were untroubled by sweet meat. Honey, vinegar, dried fruit, and spice appear routinely in surviving traditions. Monastic kitchens, governed by long fasting calendars, treated flavor as a discipline rather than a reward. The aim was not deprivation so much as control.

The mission: extract satisfaction without indulgence.

One of the few places to retain continuity with Constantinople long after it fell in 1453 was Cyprus. Hellenic cuisine spent the 20th century tidying itself up. Onions replaced fruit, sweetness was internalized. Edible accoutrements deemed too eastern were quietly escorted off the menu.

But Cyprus carried on cooking as if nothing embarrassing had happened. Lamb still arrives accompanied by dates, and without emperors wheeled out to vouch for it. Where Athens modernized and became embarrassed, Cyprus remembered.

The result is awkward for anyone who wants mutancana to be a sultan’s eccentric indulgence, because here is the same grammar—lamb, dried fruit, restraint—surviving perfectly well without conquest, myth, or a laminated portrait of Mehmed II hovering over the table.

Blurring the line between marketable mythology and older realities is in every empire’s playbook, and the Ottomans were no different.

Topkapi Palace amassed the world’s second-largest collection of Chinese celadon porcelain—over 10,000 pieces—because someone, somewhere, had convinced the court that the glaze would crack or change color in the presence of poison. Yet modern testing confirms that celadon is magnificently indifferent to arsenic, hemlock and every other fashionable toxin of the era. What the sultans actually owned was 10,000 pieces of evidence that a good sales pitch outlasts chemistry.

Seen in this light, the Mehmed II rumor looks less like fraud than translation. At some point during the 20th century, amid the professionalization of culinary heritage, some clever Turkish chef discerned that mutancana was a genuine 15th-century recipe—a fact that alone would bore most readers. So he gave the dish an owner.

Whether Mehmed II ever loved what’s arguably the best lamb dish in the galaxy is beside the point. The story survives because we prefer our history served the way airport bookshops serve ideas: a big face on the cover, the argument inside optional.

Ingredients (serves 4)

Method