Cocaine use in Türkiye has risen sharply over the past decade, shifting the issue from celebrity gossip to a nationwide public health concern, according to official data and expert assessments.

According to a report by Fulya Soybas of Hurriyet daily in Türkiye, recent police operations targeting drug-related crimes among public figures have once again brought narcotics into the public eye. High-profile raids, including an operation at a luxury hotel in the Besiktas district of Istanbul, resulted in the detention of several well-known names from the entertainment industry. Toxicology tests from an earlier investigation also revealed cocaine-positive results among other celebrities. While such cases often dominate headlines, the report underlines that the real issue goes far beyond the world of fame and celebrity culture.

Judicial statistics covering the 2015–2024 period show that the fastest-growing category of drug-related crime in Türkiye has not been trafficking, but personal use. Offenses defined under Article 191 of the Turkish Penal Code, which covers purchasing, accepting, possessing, or using drugs for personal consumption, increased more than fourfold over ten years. This sharp rise suggests that the number of users, rather than dealers, has expanded at an alarming pace.

Police data further supports this trend. In 2023 alone, more than 250,000 drug-related incidents were recorded nationwide, with over four out of five linked directly to personal use. Cocaine-related cases followed the same pattern, increasing by more than one-fifth compared to the previous year, with the majority again associated with consumption rather than distribution.

Additional insight comes from a scientific study conducted by researchers at Istanbul University Cerrahpasa Forensic Medicine Institute. By analyzing samples from wastewater treatment plants in 2019, the researchers identified cannabis and cocaine as the most commonly used substances.

In a ranking of cities where cannabis sales are not legal, Istanbul placed second, after Barcelona, in terms of cocaine indicators. Within the city, usage appeared concentrated in several districts across both residential and coastal areas, suggesting a broad and socially diverse user base.

Explaining how these figures translate into everyday reality, Professor Kultegin Ogel, Medical Director of Moodist Psychiatry and Neurology Hospital, noted that the increase has been especially visible over the past four to five years. He described the rise as almost epidemic, pointing to the COVID-19 pandemic as a turning point.

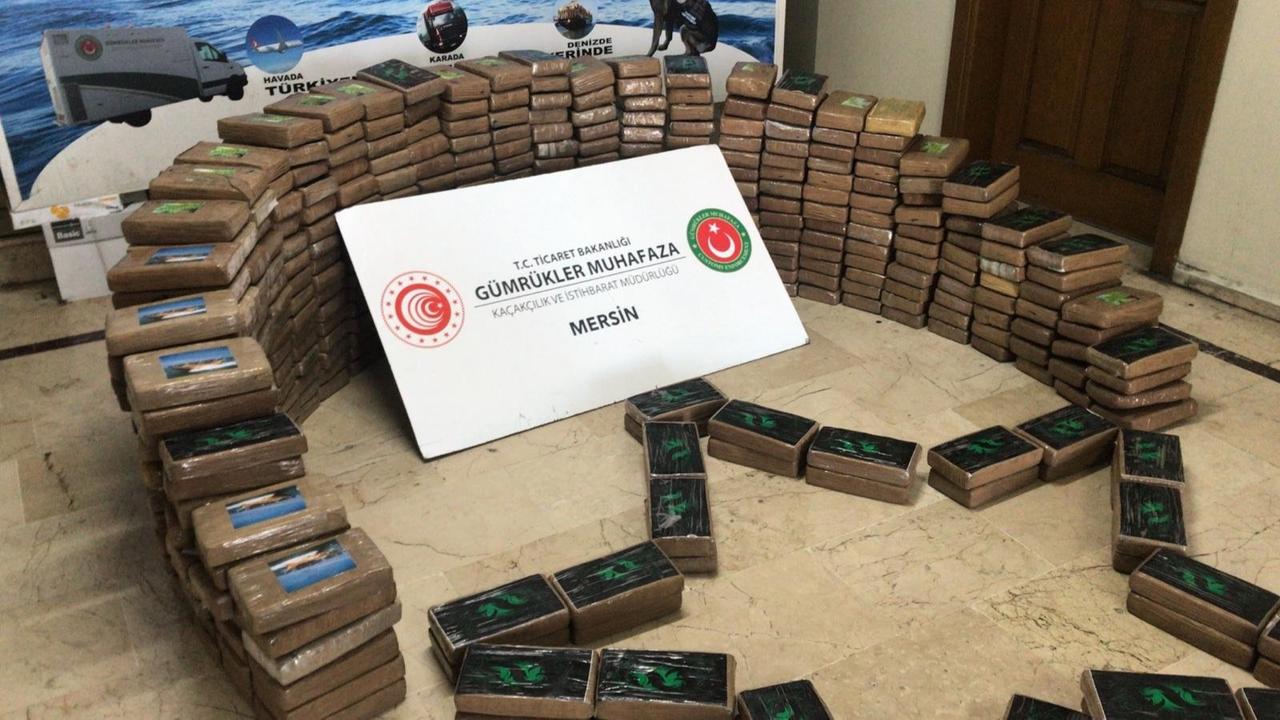

During lockdowns, drug supply methods shifted, with home delivery becoming more common, which in turn made access easier. According to patient accounts cited by Ogel, substances such as cocaine, once considered expensive and hard to find, are now widely available, indicating growing demand. In his assessment, Türkiye has moved from being merely a transit corridor to becoming a country where drugs are actively consumed.

Ogel also highlighted that drug use cuts across socioeconomic lines. Cannabis has long been socially tolerated in some circles, and other substances have gradually been added to the mix.

Synthetic drugs and methamphetamine tend to appear more often among lower-income groups, while cocaine is more common among higher, and increasingly middle, income users, some of whom reportedly rely on credit or debt to finance their habit. This broad accessibility, described as something available “for every budget,” is seen as a core driver of the problem.

Addressing common misconceptions, Ogel rejected the idea that cocaine is not addictive, calling it a persistent urban myth. He explained that cocaine is, in fact, a textbook substance for understanding addiction mechanisms. Even intermittent use can lead to dependency, as the drug rapidly depletes dopamine, the brain chemical linked to pleasure and motivation. While the immediate effects last less than an hour, the brain may take days to recover, creating a cycle of repeated use. He also warned that claims of performance enhancement are misleading, noting serious risks such as heart attacks, and brain hemorrhages.

For those seeking help, psychological counseling is available through the Green Crescent Counseling Centers (YEDAM), while medical treatment can be provided at specialized addiction clinics known as AMATEM. Ogel emphasized that although the first few months of quitting can be challenging, recovery becomes significantly easier over time.