Türkiye’s recent agreements to increase liquefied natural gas (LNG) purchases from the United States have stirred debate at home.

Opposition figures questioned why the government would opt for American LNG when allegedly cheaper and ready-to-use pipeline gas from Russia is available.

The criticism reflects a broader political discussion on energy dependency and pricing.

Yet, Türkiye’s decision is not primarily political signaling toward Washington, nor appeasing Donald Trump, and it is beyond entirely diversifying the resources.

Rather, it is rooted in the dynamics of global energy markets and Ankara’s long-term ambition to position itself as a regional hub for natural gas trade.

The government views diversification not only as a safeguard for domestic supply but also as a strategic move to transform Türkiye into a key pricing center for gas, comparable to London in metals or Rotterdam in oil.

On Tuesday, Türkiye’s Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar appeared on national TV and claimed that four different major global hubs shape natural gas prices.

The Henry Hub in the United States, the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), the Japan-Korea Marker (JKM), and the U.K.’s National Balancing Point. Among these, the Henry Hub consistently offers the lowest prices, often cheaper even than Russian supplies.

In comparison, the TTF in the Netherlands can be four to five times more expensive than U.S. benchmarks.

The JKM, covering East Asia, typically records even higher prices due to transport distances, while the U.K. hub reflects its own regional dynamics.

Türkiye’s energy policy involves leveraging these differences, with American LNG increasingly standing out as a competitive option despite transportation and liquefaction costs, in contrast to the claims that Russian gas is way cheaper in Turkish media.

LNG imports are not new to Türkiye. Since 1994, Ankara has purchased gas from over 20 countries, including Algeria, Nigeria, and Qatar.

The mix has included long-term supply contracts lasting up to 15 years as well as short-term spot purchases, particularly in harsh winters when demand spikes.

Currently, around 10% of Türkiye’s gas supply comes from the United States, transported as LNG by tanker.

This share was already in place before the recent agreements, which only extend and secure supplies further into the medium and long term.

The last deal, per se, only means shifting from ad hoc winter spot deals to more predictable supply arrangements.

While Henry Hub prices are the lowest globally, delivering US LNG to Türkiye involves multiple layers of cost.

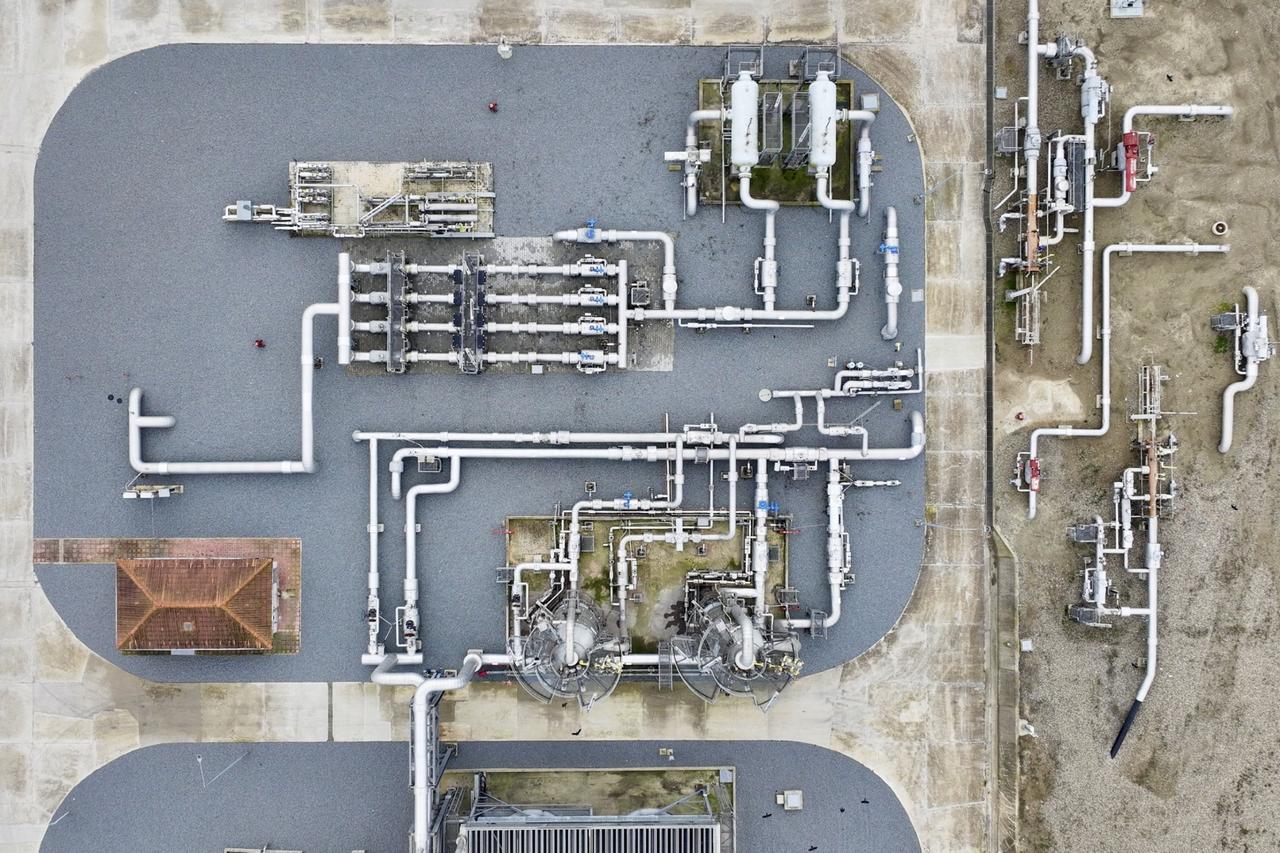

Gas must first be transported to liquefaction terminals in the U.S., cooled and converted into LNG, shipped across the Atlantic, and then regasified at Turkish facilities in ports such as Aliaga and Dortyol.

Even after accounting for these expenses, American LNG remains one of the most competitive options, especially from 2027 onward when Türkiye’s infrastructure investments will further optimize import costs.

Ankara’s strategy is to ensure that the country remains flexible and well-supplied regardless of volatility in European or Asian markets.

Türkiye’s gas import contracts from Russia, Iran, and Azerbaijan often use oil-indexed or hub-indexed pricing formulas.

This creates vulnerabilities when crude prices surge or when European markets fluctuate sharply, as seen during the energy crisis following Russia’s war in Ukraine.

To manage these risks, Türkiye is pushing to adjust some contracts away from European benchmarks like TTF, favoring more predictable and diversified formulas.

The inclusion of U.S. LNG in this portfolio strengthens Türkiye’s bargaining position, providing leverage in negotiations with traditional suppliers.

At the same time, domestic production is gradually reshaping the picture. Gas extracted from the Black Sea has already begun to supply households, reaching around 4 million homes.

This number is expected to double to 8 million within a year, marking a significant step toward reducing import dependency.

With 22 million households connected to natural gas across Türkiye, the expansion of domestic supply plays a crucial role in easing demand pressures while strengthening energy security.

Türkiye needs time to achieve its goals. Meanwhile, the partners have their concerns, such as the one Trump made during the recent meeting about buying oil from Russia. The request, however, wasn't about gas.

The broader goal is not only about securing energy for domestic consumption but also about re-exporting and shaping prices regionally.

By importing from multiple sources, including the U.S., Türkiye aims to establish Istanbul as a natural gas trading hub with its own pricing index.

By hosting large storage facilities and a diversified supply portfolio, Türkiye hopes to attract regional buyers and traders, eventually turning its geographic position into an economic advantage.