If every vehicle in Türkiye were electric, the country’s energy security and economic balance would look fundamentally different, and the debate is no longer hypothetical. It is the strategic logic shaping Ankara’s accelerating push into electric mobility, one that has already placed Türkiye ahead of much of Europe.

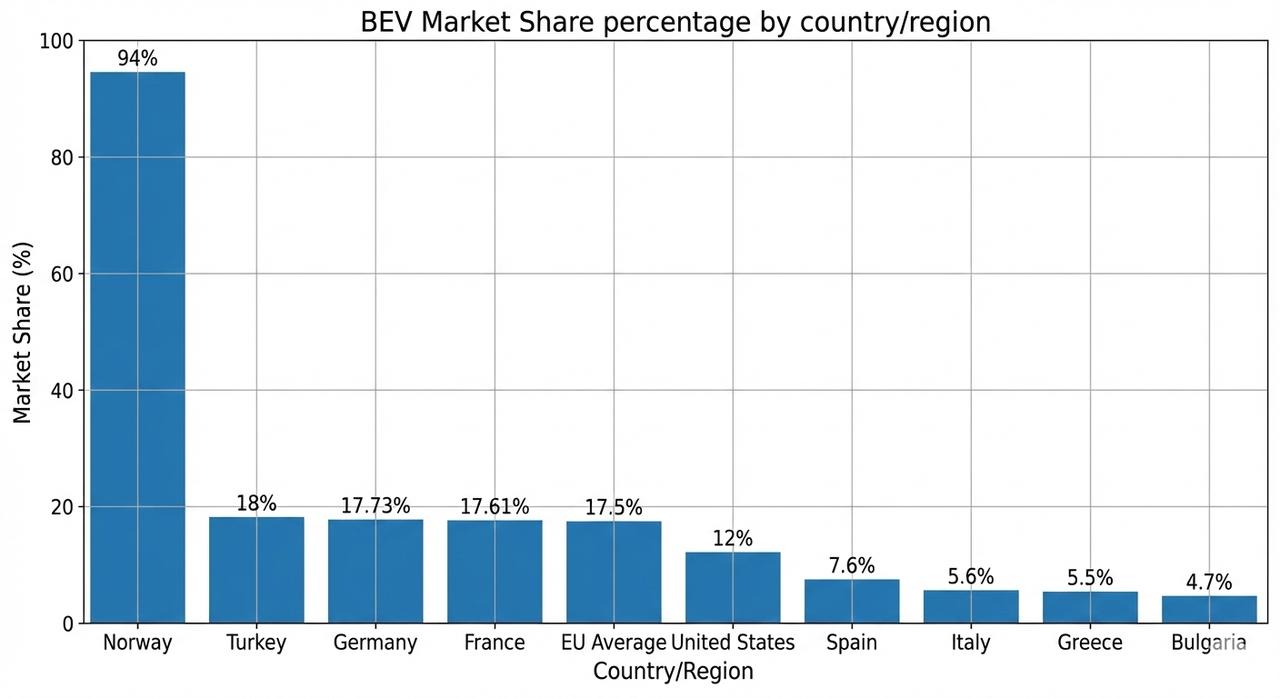

Last year, electric vehicles (EVs) accounted for roughly 18% of new car sales in Türkiye, exceeding the European average of 17% and outpacing markets such as Germany, France, and Italy. Total EV sales reached 164,650 units, marking an 11% annual increase. For a country that imports close to 90% of its crude oil, this transition is less about environmental ambition than macroeconomic necessity.

The energy gap sits at the center of Türkiye’s current account deficit. Reducing petroleum dependence through electrification offers one of the few structural tools capable of delivering sustained economic relief.

The energy arithmetic behind Türkiye’s electric transition is straightforward. According to the Energy Market Regulatory Authority’s (EPDK) 2024 electricity report, almost half of Türkiye’s electricity comes from renewable sources. Hydropower accounts for 22%, followed by wind (11%), solar (8%), biomass (3%), and geothermal energy (3%).

The remaining half is generated from fossil fuels, primarily natural gas and coal. Natural gas alone makes up 19% of electricity production and is almost entirely imported. Coal production is divided between imported coal (22%) and domestically sourced lignite, hard coal, and asphaltite, which together account for 14%.

Taken together, approximately 40% of Türkiye’s electricity is produced using imported energy sources, while 60% relies on domestic inputs.

Moving road transport from oil, where import dependence is close to 90%, to electricity effectively cuts external energy exposure by more than half.

This shift has direct macroeconomic consequences for the country. Lower import bills ease pressure on foreign exchange reserves and reduce exposure to global energy price volatility.

Unlike petroleum, electricity production offers multiple domestic pathways. Annual growth in solar and wind capacity, combined with the prospect of nuclear generation, provides Türkiye with options unavailable in oil-based transport.

France offers a reference point. Despite lacking significant oil or gas reserves, the European country generates roughly 70% of its electricity from nuclear power, positioning itself as one of the European Union’s strongest proponents of electric vehicles.

Türkiye’s electric transition also intersects with urban efficiency. In 2024, Istanbul ranked as the city where drivers lost the most time to traffic congestion worldwide. Electric vehicles do not resolve congestion itself, but they materially reduce its economic cost distinctively.

Internal combustion engines perform worst in stop-and-go traffic, where fuel consumption per kilometer peaks and mechanical wear accelerates. Braking systems, transmissions, and engines degrade faster under these conditions, raising maintenance costs and shortening vehicle lifespans.

Electric vehicles, on the other hand, exhibit the opposite profile. Regenerative braking converts deceleration into stored energy, reducing consumption in urban traffic. One-pedal driving minimizes brake wear, while electric motors deliver maximum torque without multi-gear transmissions. The result is lower operating costs and longer vehicle lifetimes.

For a city defined by congestion, these efficiencies accumulate into national-level gains. Reduced energy waste, lower maintenance imports, quieter streets, and the elimination of tailpipe emissions carry economic value beyond individual consumers.

Despite Türkiye’s favorable EV tax structure, European manufacturers have been reluctant to expand electric offerings in the Turkish market. This reluctance stems from the European Union’s carbon emission regulations.

Under EU rules, automakers face heavy penalties if fleet-wide emissions exceed defined thresholds, while staying below them brings regulatory relief. To manage this balance, manufacturers prioritize electric sales within the EU, where they directly offset emissions from combustion vehicles.

Markets outside the EU, including Türkiye, become outlets for higher-margin gasoline and diesel models. In practice, this means European brands limit EV supply or price electric models uncompetitively, even where tax systems favor them.

Recent pricing strategies illustrate this distortion. In some cases, electric versions of vehicles are sold at higher prices than hybrid equivalents in Türkiye, despite lower taxes.

When compared with European pricing, the electric model aligns with EU prices, while the hybrid is discounted well below its European counterpart, an inversion designed to preserve combustion vehicle sales in Türkiye.

This dynamic actively constrains Ankara’s electric transition while protecting European manufacturers’ internal emission balances.

Turkish public long questioned the VAT on Türkiye’s domestically made EV brand Togg. However, this largely stems from the Customs Union agreement with the EU, as it prevents direct tax exemptions that would privilege domestic production, ruling out zero-tax treatment.

Instead, Ankara relies on indirect support mechanisms. Current EV tax brackets align closely with Togg’s technical specifications, particularly its 160 kilowatt (kW) motor output, placing it within favorable thresholds.

State-owned banks offer zero-interest loans and extended financing terms unavailable for competing models, shaping consumer choice through credit access rather than pricing alone.

Public procurement provides another layer of support. Regulations allow fleet replacement only with electric vehicles exceeding 40% domestic content, a criterion currently met only by Togg. These measures create demand stability but stop short of delivering the scale required for full energy transformation.

Norway’s experience demonstrates what sustained policy alignment can achieve. By October 2025, electric vehicles accounted for 98.4% of new car sales. This outcome was driven by a comprehensive incentive structure.

Electric vehicles were exempt from weight-based and emissions taxes, as well as the standard 25% VAT. The electric cars gained access to priority lanes, free toll roads and ferries, and free state and municipal parking. Corporate tax advantages encouraged fleet electrification, while dense charging infrastructure removed daily friction.

Türkiye has replicated the fiscal core of this model. Electric vehicles face minimum tax rates of 25%, compared to rates approaching 80% for combustion vehicles. This alone has lifted EV market share above the European average.

What remains missing are complementary urban and infrastructure incentives. Municipal parking exemptions, dedicated EV parking zones, or toll-free highway corridors would significantly strengthen adoption, particularly in cities with acute parking shortages. Norway’s experience shows that such measures shape behavior as effectively as price signals.

Rather than competing in a mature technology dominated by century-old manufacturers, Türkiye has chosen to enter electric mobility, where technological shifts reset competitive positions. Now it's time for it to use a market of 90 million people to leverage its independence in economic and energy aspects.