On Thursday, NATO leaders, including President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, gathered in The Hague for what became one of the alliance’s most consequential meetings in recent memory.

The summit concluded with a landmark decision: raising the collective defense spending target from 2% to 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2035.

While framed as a long-term response to Russia’s military assertiveness and growing demands for civil and military resilience, the political momentum behind the increase owes much to U.S. President Donald Trump’s push to hold allies accountable. While many European countries have yet to meet even the previous 2% benchmark, the new figure is intended to leave little room for underperformance.

The new target is divided into two components: 3.5% of GDP will be directed toward traditional defense expenditures, such as military personnel and equipment, while the remaining 1.5% is earmarked for security-related infrastructure aimed at boosting civil resilience.

Türkiye, which already exceeds the 2% spending benchmark, was among the early supporters of the new framework. The country also claims to have met all its NATO capability targets and continues to develop its domestic defense sector as a strategic priority.

Ankara has already mapped out its main spending priorities for reaching the goal. Investments in layered air defense, long-range missile systems, and unmanned military platforms are expected to drive the bulk of Türkiye's increased outlays over the coming decade.

While many NATO members still fall short of the previous 2% threshold, Türkiye has already surpassed it and positions itself among the top five contributors to NATO operations and missions. Ankara argues that it meets all alliance capability pledges and continues to scale its domestic defense industry as a national priority.

But moving from 2% to 5% of GDP is a different challenge altogether. Turkish economic policy remains under pressure from inflation, currency volatility, and tight fiscal space. Instead of ramping up spending across the board, Ankara appears to be concentrating its budgetary expansion around systems that provide strategic deterrence and autonomy.

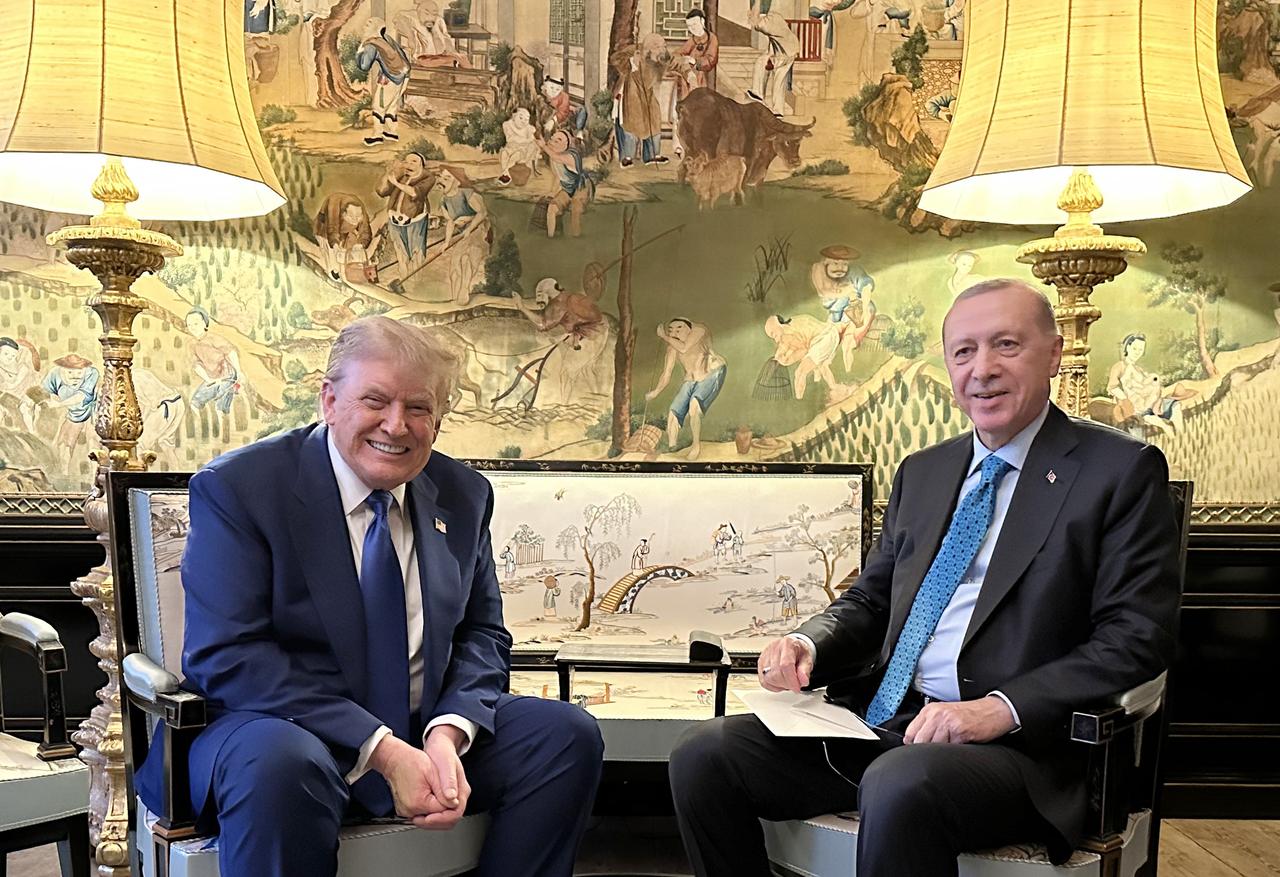

One of the key topics during Erdogan's meeting with Trump at the NATO summit was the lifting of CAATSA sanctions and the delivery of the F-35 jets that Türkiye had already paid for. Now prioritizing its own air defense program, Ankara appears to be moving past the deadlock caused by its earlier purchase of Russian S-400 systems.

While the national "Steel Dome" remains in the development phase, Turkish officials insist it is central to the country's long-term defense posture, suggesting a timeline that will extend well beyond the current NATO benchmark window.

Turkish officials confirm that the “Steel Dome” project—a national, layered missile defense system—is at the center of future planning. The initiative aims to build a network of systems capable of responding to threats at various altitudes, integrating radar, electronic warfare, and missile capabilities.

Recently, following the unprecedented rounds of conflict between Iran and Israel, Erdogan signaled a renewed focus on missile development during a televised address to the nation. He stated that Türkiye is revising its missile production planning “to bring our stock of medium- and long-range missiles to a credible level of deterrence” in light of recent regional developments.

Though Türkiye currently lacks operational long-range ballistic missiles, developments in its domestic missile program suggest this may change soon. Turkish media have reported that the military industry is working on extending the range of the Roketsan-produced "Cenk" missile—originally a medium-range system with a 2,000-kilometer range—to potentially exceed 3,500 km.

Cenk is derived from the shorter-range "Tayfun" missile, itself developed from experience with the “Bora” tactical ballistic missile, used in cross-border operations in northern Iraq and Syria.

Erdogan hinted that "in the not-too-distant future," Türkiye would reach a deterrence capacity sufficient to prevent any actor from “daring to challenge" it.

These statements were followed by confirmation that Türkiye now possesses systems with an range exceeding 800 km, and that development of missiles exceeding 2,000 km in range is being accelerated. While no long-range missile has yet been publicly unveiled, Erdogan’s emphasis suggests an official rollout may be imminent.

For now, Ankara appears to be relying more on industrial growth and capability development than on sheer budget expansion. The Turkish defense sector, dominated by firms like Aselsan, TAI, and Roketsan, has grown its export capacity and is increasingly able to supply the Turkish Armed Forces with drones, naval systems, and guided munitions produced domestically.

This industrial development strategy offers Ankara more flexibility than some NATO members who rely heavily on foreign procurement, but it does not necessarily translate into a direct path toward meeting a numerical GDP target.

Türkiye’s posture stands in contrast with several European NATO members that have resisted the new benchmark on both fiscal and political grounds. Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez described the target as “unreasonable and counterproductive,” citing budgetary pressures and political resistance to austerity or tax hikes.

Many European militaries face a broader structural issue: despite high spending levels, NATO officials have repeatedly warned that European forces are under-equipped and under-prepared. The EU collectively spent €326 billion ($382.2 billion) on defense in 2024—nearly three times Russia’s estimated budget—yet procurement inefficiencies and fragmentation limit its overall readiness.

In this context, Türkiye’s centralized procurement strategy and consolidated military-industrial base could become a point of leverage in future NATO planning. Its ability to produce a wide range of systems domestically, including drones, missile systems, and naval platforms, positions it as both a contributor and a potential supplier in an alliance where cost-effective capabilities are increasingly in demand.

Long before Ankara endorsed NATO's push for increased defense spending, unmanned platforms had already emerged as the backbone of Türkiye’s modern military doctrine.

The 2025 defense agenda reflects this hierarchy clearly: while missile programs and air defense systems are growing priorities, unmanned systems remain the foundation, both as a proven capability and a political statement of industrial self-reliance.

What sets these programs apart is not just technological ambition, but institutional priority. In budget planning and procurement cycles, unmanned systems are no longer treated as force enablers—they are the primary asset around which other capabilities are integrated.

The revenue generated from this sector not only fuels the appetite for increased spending but also helps secure broader support for it.

With increased defense funding on the horizon, the expectation within Turkey’s defense establishment is that unmanned systems will continue to serve as a fast-moving domain—both for deterrence at home and exports abroad.