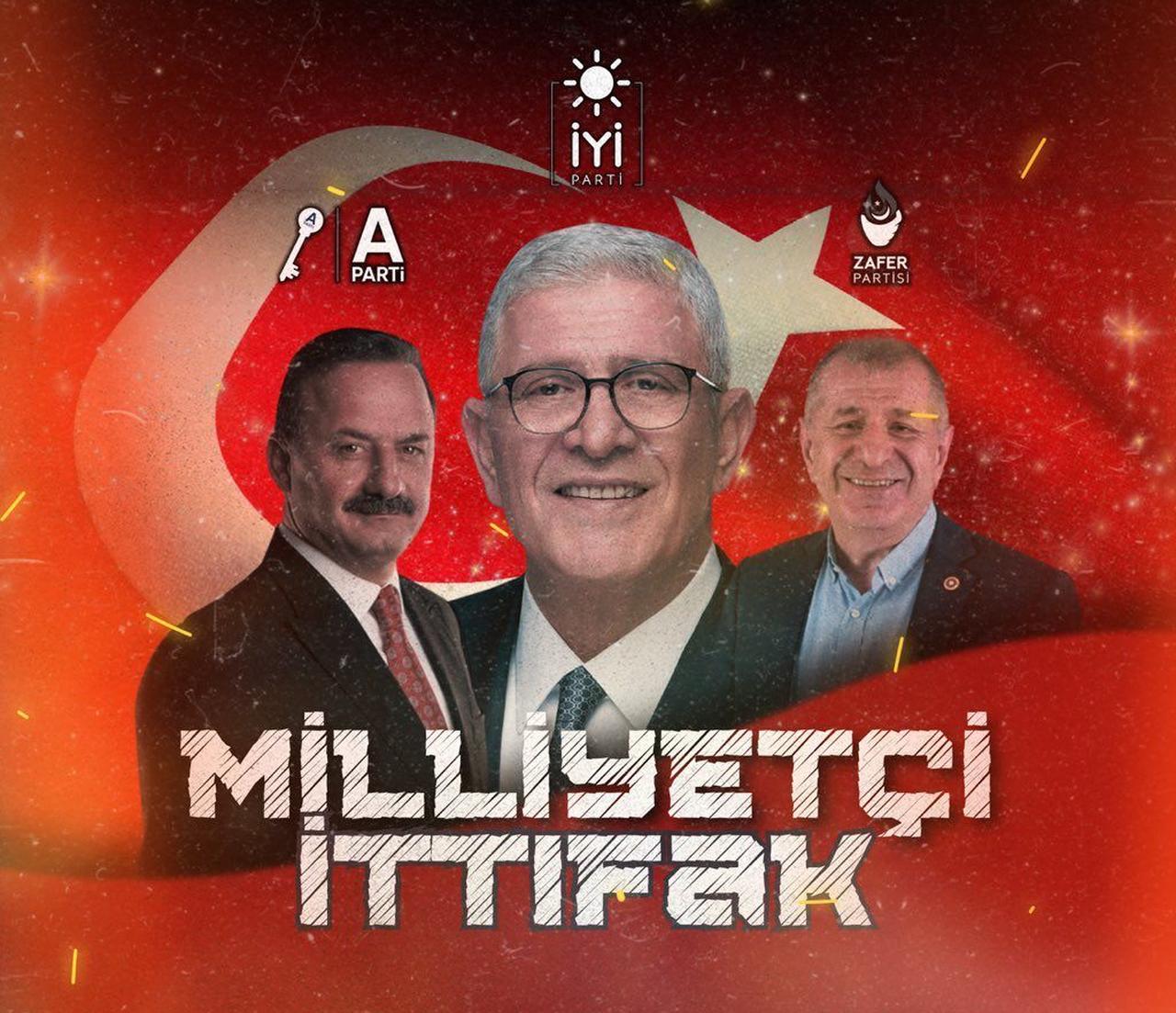

A new debate is brewing in Turkish politics over the possible merger of nationalist parties—the Good Party (Iyi Party), the Victory Party (Zafer Partisi), and the recently founded Key Party (Anahtar Party).

The idea, while still in its early stages, has already stirred speculation about whether a unified nationalist bloc could reshape the opposition landscape ahead of the next elections.

The conversation gained traction after Good Party leader Musavat Dervisoglu and Victory Party head Umit Ozdag appeared together at the Nationalist Congress Association’s recent gathering.

Ozdag openly questioned why nationalist factions remain divided, while Good Party leader Dervisoglu’s response was notably conciliatory, signaling openness to future collaboration and insisting that personal and strategic differences had never amounted to a permanent split.

While such statements have revived talk of a potential alliance, the road to unity remains uncertain.

All three parties share common ideological roots—most notably, their origins within the Good Party, itself a splinter from the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

But despite their shared base and similar rhetoric, structural challenges and limited voter appeal continue to weigh heavily on their prospects.

The three nationalist movements have a history of cohabitation. Many of today’s party figures once operated under the Good Party umbrella before branching out due to internal disagreements over leadership and political strategy.

However, their secular-leaning nationalist core electorate remains largely the same, raising doubts about whether uniting these factions would meaningfully expand their influence.

None of these parties currently enjoys broad appeal beyond their dedicated base. Analysts note that each struggles to attract centrist or urban liberal voters, leaving them confined to the margins of Türkiye’s political spectrum.

Key Party leader Yavuz Agiralioglu, who could potentially join such an alliance, represents the more conservative wing of Turkish nationalism, as he remains disillusioned with the nationalist-conservative MHP in the ruling bloc, unlike the other secular-nationalist parties.

Yet it is not even certain that these figures, who were previously united in the Good Party, can unite again.

Despite frequent calls for unity, the potential alliance risks being more symbolic than transformative.

Türkiye’s broader opposition, led by the Republican People’s Party (CHP), has its own tensions when it comes to cooperation.

Many CHP supporters advocate for consolidating all anti-government votes under one major umbrella, believing that only a unified front can challenge the ruling bloc effectively.

This mindset often sidelines smaller movements. The experience of Muharrem Ince—a former CHP lawmaker who attempted to form an independent presidential bid but was met with fierce backlash—remains a vivid reminder of how hostile opposition voters can be toward perceived “vote-splitters.”

In that environment, a nationalist merger may be viewed less as an opportunity for pluralism and more as a threat to opposition unity.

Nationalist movements in recent years built much of their momentum on anti-refugee sentiment, particularly the presence of millions of Syrians in Türkiye.

Yet as conditions in Syria improve and voluntary repatriations increase, the potency of that narrative appears to be waning.

With thousands of Syrians returning home monthly and the refugee issue losing its sense of urgency, nationalist rhetoric has struggled to maintain the same resonance it once had.

This shift particularly weakens the Victory Party, which rose to prominence on an anti-immigration platform. As migration pressure eases, the party’s defining issue risks fading from the public agenda.

Even if talks advance, it is far from certain that all three parties could genuinely merge. Beyond ideological compatibility, leadership ambitions and personal rivalries pose significant obstacles.

None of the groups currently surpasses the electoral threshold on its own, yet their combined strength could, in theory, yield a more visible political force.

According to political observers, the three together could surpass the 10% mark—a critical psychological and electoral barrier—potentially carving out a distinct space in the nationalist segment of Turkish politics.

But such an outcome would depend not only on unification but also on maintaining internal harmony and coherent messaging, something that has eluded nationalist factions for years.

Yet there is a certain social media hype around the idea of uniting these nationalist parties, whose core base largely exists online.

However, Turkish politics is far more complex than simple alliances and splits, and any such merger would immediately generate its own opposition, like a more consolidated Kurdish political movement.