This article was originally written for Türkiye Today’s bi-weekly Balkans newsletter, BalkanLine, in its Dec. 5 issue. Please make sure you are subscribed to the newsletter by clicking here.

The geopolitical tightrope walk that Belgrade has performed for over a decade effectively ended this week, not at a diplomatic summit, but at the gates of the Pancevo Oil Refinery. Following the U.S. refusal to renew the operating license for the Russian-majority-owned Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS), operations have been suspended.

Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic’s announcement on Tuesday confirmed the worst: “I am disappointed. We have decided that the refinery will end its operations, but we also agreed that salaries and similar payments will be settled by the weekend.”

But to understand the actual depth of this crisis, we must look beyond the barrels of oil to the architecture of influence itself. For 17 years, NIS was one of the pillars of Moscow’s presence primarily in Serbia and broadly across the Balkans, acquired in 2008 as the geopolitical price for Russia's U.N. veto on Kosovo. Today, that asset has turned into a toxic liability.

Moscow's refusal to facilitate a pragmatic exit suggests a cynical calculation: prioritizing its own leverage over the economic stability of its "sincere friend." This approach risks eroding the very public trust that has been the bedrock of their alliance, proving that for the Kremlin, Serbia’s stability is secondary to Russia’s strategic hold.

The shockwaves are already hitting the financial sector. The threat of secondary sanctions has moved from a possibility to an immediate danger. Vucic said prolonging NIS's links with the government could risk secondary sanctions and "the destruction of the Republic of Serbia's financial system".

Last week, the National Bank of Serbia flagged serious concerns about exposure, and while NIS, which supplies 80% of Serbia’s fuel, has been granted a brief window to settle payments and pay employees this week, the broader banking sector is effectively freezing it out to avoid being caught in the U.S. crosshairs.

However, I should remind you that experts caution that this rupture does not guarantee a pivot to the West.

Belgrade likely dragged its feet on a solution until the last moment, hoping that a new Trump administration might relax enforcement, a gamble that has evidently failed. Now, the government’s preferred exit strategy isn't necessarily a Western buyer, but a partner like China or the UAE.

A potential deal with the Emirates is particularly attractive; as a "proven partner" with strong ties to both Washington and Moscow, a UAE takeover could be sold to the Serbian public as a strategic win rather than a capitulation.

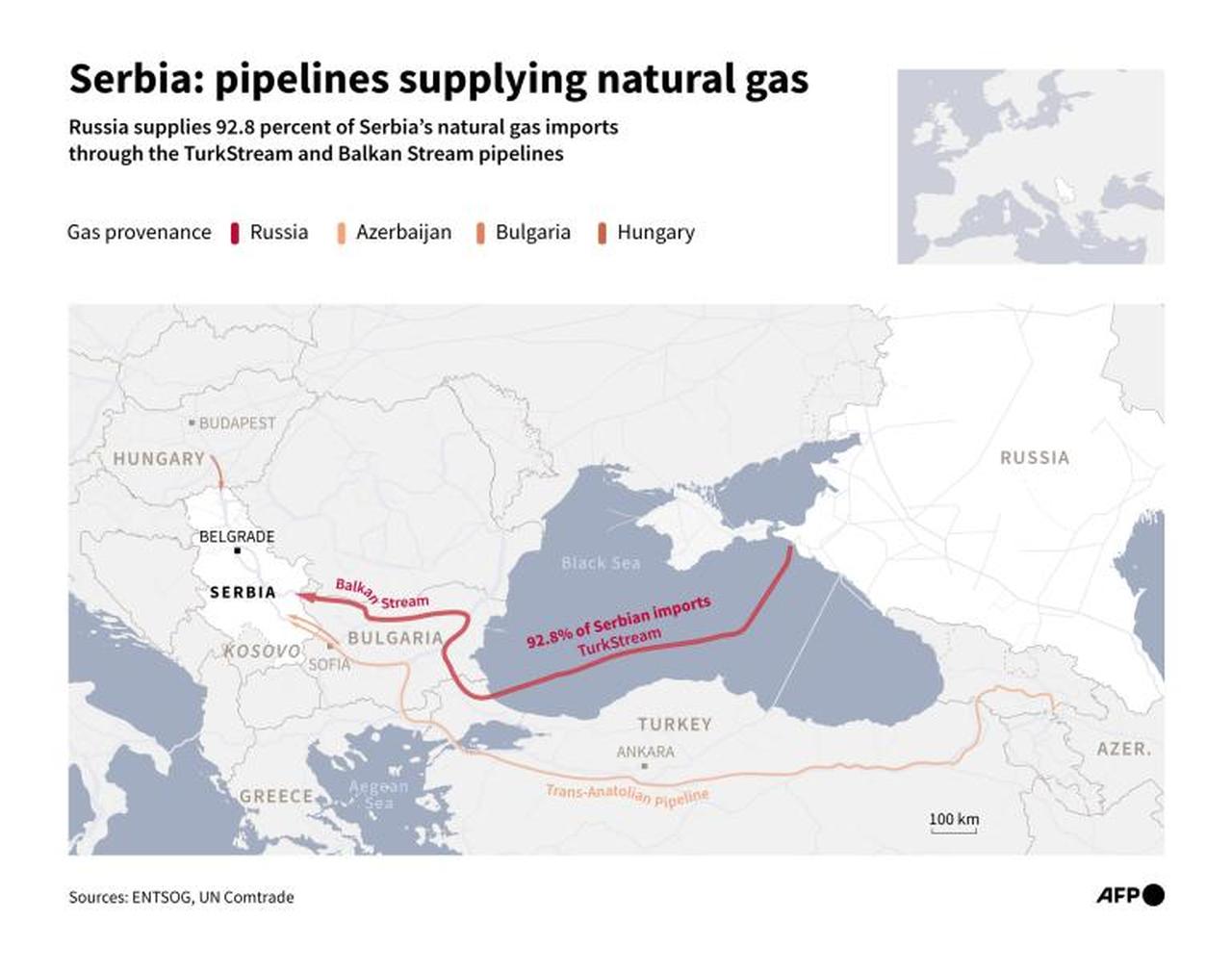

However, the path forward is fraught with risk. Washington has made it clear that Russia’s share must transfer to a company demonstrably independent of Moscow's control. Furthermore, even if the oil crisis is resolved, Russia retains a potent weapon: gas. Meanwhile, parallel supply discussions continue between Belgrade and Moscow. Russia provides about 90% of Serbia’s gas, and the current contract expires at the end of December.

Mistrust is growing, but Moscow could still leverage gas supplies and pricing to punish Serbia’s leadership, reminding Belgrade that escaping one form of dependence may only tighten another knot.

The shutdown proves that Russian influence in the Balkans is brittle when confronted with hard Western economic power.

Moscow’s refusal to facilitate a smooth exit has transformed NIS from a symbol of alliance into a symbol of dysfunction, potentially doing more damage to Russian soft power in Serbia than any Western diplomatic initiative ever could.

The jug has gone to the water for the last time, and it is Serbian citizens, not Gazprom shareholders, who are stepping on the shards.