In a move that could lessen geopolitical tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean, Greek Cypriot President Nikos Christodoulides announced plans to use his country’s upcoming presidency of the Council of the European Union to improve ties with Türkiye, a forever-candidate for full EU membership and NATO’s second-largest military power.

Christodoulides told Politico on Dec. 10 that the Greek Cypriot side would facilitate “positive steps in EU-(Türkiye) relations” in return for Ankara allowing his country to join NATO’s “Partnership for Peace” (PfP) program, with the ultimate aim of “resolving the Cyprus problem within the agreed framework.”

Founded in 1994 to foster better understanding between the alliance and former members of the Warsaw Pact, as well as neutral European states such as Austria, Ireland, and Switzerland, participation in PfP is often seen as a step toward full NATO membership. Most Warsaw Pact countries are now NATO allies.

Christodoulides’s suggestions make a lot of sense, and he should be commended for taking such a bold step that has eluded most Greek Cypriot leaders since 1974, when the military junta in Greece staged a military coup on the island to annex it, leading Türkiye to intervene as part its role as guarantor of Cyprus’s independence under the London-Zurich Accords of 1959 and the Treaty of Guarantee of 1960.

But much work is required to even come close to Greek Cypriot participation in PfP/NATO and improving Türkiye-EU ties.

Part of the Ottoman Empire from the early 16th century and then a British possession from 1878 until 1960, Cyprus has produced outsized geopolitical drama compared to its size—the small eastern Mediterranean island is one-third the size of Belgium and two-thirds of the US state of Connecticut.

Upon independence in 1960, the Republic of Cyprus succumbed to ethnic strife between the Greek majority and Turkish minority, with the latter group suffering much more.

Following Greece’s coup attempt in 1974, and 16 rounds of talks for the next 51 years—including a UN-backed plan that was put to a popular referendum approved by Turkish Cypriots and rejected by Greek Cypriots in 2004—the island remains divided between the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which only Türkiye recognizes, and Greek Cyprus, which the international community accepts as the sole government on the island.

Türkiye refuses to recognize Greek Cyprus and refers to it as “the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus.”

The six-month rotating presidency of the Council of the EU, which Greek Cyprus will assume on Jan. 1, enables the chair country to set the agenda for EU ministerial meetings and coordinate EU legislation with the European Parliament, elected in direct popular vote by the citizens of its 27 members. During its presidency, Greek Cyprus is expected to focus on Russia’s war on Ukraine and EU defense.

To that end, the European club has already created the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) program that will allocate €150 billion in “long-maturity loans to Member States requesting financial assistance for investments in defense capabilities.” Despite initial interest, Türkiye backtracked from applying to SAFE when Greece and Greek Cyprus signaled their intention to condition Turkish participation to unrealistic concessions from Ankara.

The episode proves why any sort of normalization between Türkiye, Greek Cyprus, TRNC, and Greece is so hard.

For one, given that Russia’s war on Ukraine is likely to continue into the new year and reach its fourth anniversary in February, and with Europe nowhere near addressing its geopolitical shortcomings vis-à-vis Moscow and therefore requiring better ties with Ankara, Greek Cyprus needs NATO more than Türkiye needs SAFE.

For Ankara, which signed its first association agreement with then-European Economic Community in 1963, gained candidacy status in 1999, and started accession negotiations in 2005, full EU membership is an even more distant dream. No accession talks have taken place since 2018.

Even if Türkiye fulfills all the requirements toward full membership by successfully opening, implementing, and closing all 35 negotiation chapters and resolving the Cyprus question, it is doubtful the Greek Cypriot side could deliver membership to Ankara.

Leading EU member France has a constitutional clause that allows its leaders to hold a popular referendum before a candidate country joins the European club, a measure implemented in the 2000s to block Ankara’s prospective accession. Likewise, Austria’s political elites have been repeating since the 2000s that any Turkish membership in the EU would have to go through a plebiscite.

That is not to say there is no way to lessen tensions across the Green Line in Cyprus. Türkiye and Greece, as well as international stakeholders such as the EU and the United States, could contribute. But all sides need to recalibrate their mindsets.

Greek Cypriots and Greece (and many EU leaders) often betray a misguided assumption that they could bully Türkiye and get their wishes in removing Turkish forces from the island, dismantling the Turkish Cypriot state, and reunifying Cyprus. Greek American lobbies tried that at the US Congress following the 1974 crisis, which resulted in a US arms embargo on Türkiye, which only hardened Ankara and Turkish Cypriots’ resolve.

While Ankara does wield influence in Turkish Cypriot affairs, it does not dictate terms to Turkish Cypriots—in fact, it often follows their lead.

For example, in the run-up to the TRNC’s independence on November 15, 1983, at the same time when Türkiye was transitioning from a military regime to a democracy, the government formation process in Ankara meant that it could do little to block Turkish Cypriots’ unilateral declaration of independence. Independence took place in large part at the initiative of legendary Turkish Cypriot leader and first TRNC President Rauf Denktas.

Failure to address Turkish Cypriot demands for a bizonal federation and additional guarantees to avoid the pre-1974 bloodshed led to the independence of the TRNC.

Similarly, Türkiye became more vocal about a two-state solution in Cyprus instead of a bizonal federation once the last comprehensive reunification talks at the Swiss town of Crans-Montana failed in 2017 and the Turkish Cypriot parliament passed resolutions to that effect, most recently on Oct. 14.

Thus, instead of trying to negotiate with Ankara over the head of Turkish Cypriots (a majority of whom want Turkish troops to remain on the island even if there is reunification), Greek Cypriot leaders would do well to engage their neighbors to the north and take incremental steps that could lessen tensions between north and south, as well as Türkiye and the EU.

Ending the isolation of Turkish Cypriots, even if partially, would be a good start. This community of nearly 300,000 people has faced comprehensive Greek Cypriot embargoes since 1974 that bar them from virtually any meaningful participation in global affairs. Turkish Cypriots’ only connection to the outside world—flights, trade, telecommunications—is through Türkiye.

A full lifting of sanctions would be a tough proposition for any Greek Cypriot president, but Christodoulides could at least remove some of the restrictions on Turkish Cypriots, for example, by enabling them to sell some of their agricultural produce to the EU directly. Another goodwill move would be to enable Turkish Cypriot sports clubs and athletes to hold friendly matches with their Greek Cypriot peers and those from third countries.

If such confidence-building measures bear fruit, cooperation in water and disaster management, especially forest fires, an even bigger problem in the era of climate change, could lead to bigger and better things.

A sine qua non of any normalization in Cyprus would require halting, or at least slowing down, the deployment of new defense items on the island.

For several years, a serious military buildup on the Greek Cypriot side has taken place, where several naval and land-based installations have expanded and new ones built, much of it with Greek, US, European, and Israeli help. Greek Cyprus’s deployment of the Israeli-made air defense system Barak MX has deepened suspicions on the Turkish side, leading Türkiye to introduce its world-famous drones to TRNC bases to keep an eye on developments.

Should Turkish Cypriots, Greek Cypriots, and Türkiye establish channels of communication through which they could avert potential crises or misunderstandings, they could also ask outside stakeholders such as EU members France and Greece, as well as the United States and the United Kingdom, to coordinate their military activities in southern Cyprus with TRNC as well as Türkiye.

With such enlightened behavior by the various sides, Greek Cypriot participation in PfP and improved Türkiye-EU ties would be a no-brainer.

But the most critical confidence-building measure would have to be the one that simply cannot be done in a few months or even a few years: Confronting the past and avoiding its misuse.

Greece and Greek Cypriots understandably see the 1974 crisis as the painful division of the island, but they hardly help their case by holding rallies where they use symbols that remind Turkish Cypriots of the tragic memories of the pre-1974 period. Similarly, Türkiye and Turkish Cypriots’ celebration of the 1974 intervention rubs Greeks and Greek Cypriots the wrong way.

Commemorating the past could be done in a more respectful way, which would lead to talking about history in a less emotional and more intelligent way.

Normalizing with Türkiye should start with normalization in Cyprus, and there, an unconventional case comes to the fore.

In recent years, the most visible attempt at facing the bloody troubles before 1974 has come from YouTuber-turned-MEP Fidias Panayiotou. The 25-year-old Panayiotou, a Greek Cypriot, has managed to turn his online following into votes at the European Parliament elections in July 2024, and has hosted his fellow social-media personality Ibrahim Beycanli (“Urban Cypriot”) from TRNC, as well as the previous lead negotiators of TRNC and Greek Cyprus.

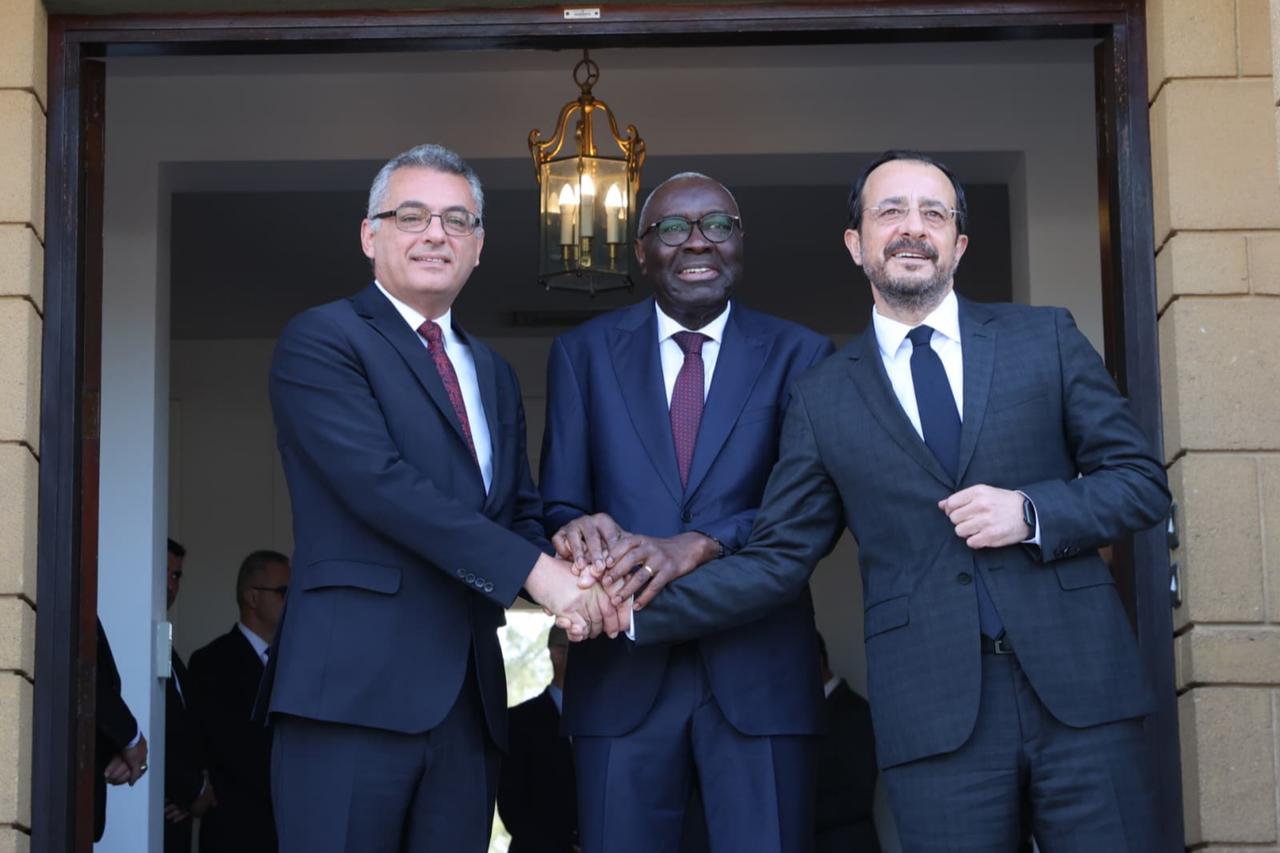

There is something to be said about younger people coming up with new ideas or at least new ways to talk, a point that applies to both Christodoulides and the new TRNC president, Tufan Erhurman. The Turkish Cypriot leader, an advocate of federal reunification, was all of five years of age in the summer of 1974, and Christodoulides was barely 7 months old.

One could do worse than have the courage of a neophyte influencer-turned-politician to talk about the past and think about the present.