Protests have taken Iran by storm and Türkiye by surprise, forcing Ankara into a cautious posture.

The Iranian government has slowed down the internet, which means receiving reliable information has become a challenge, but the Oslo-based group Iran Human Rights reported that more than 3,400 people have been killed as of Jan. 14.

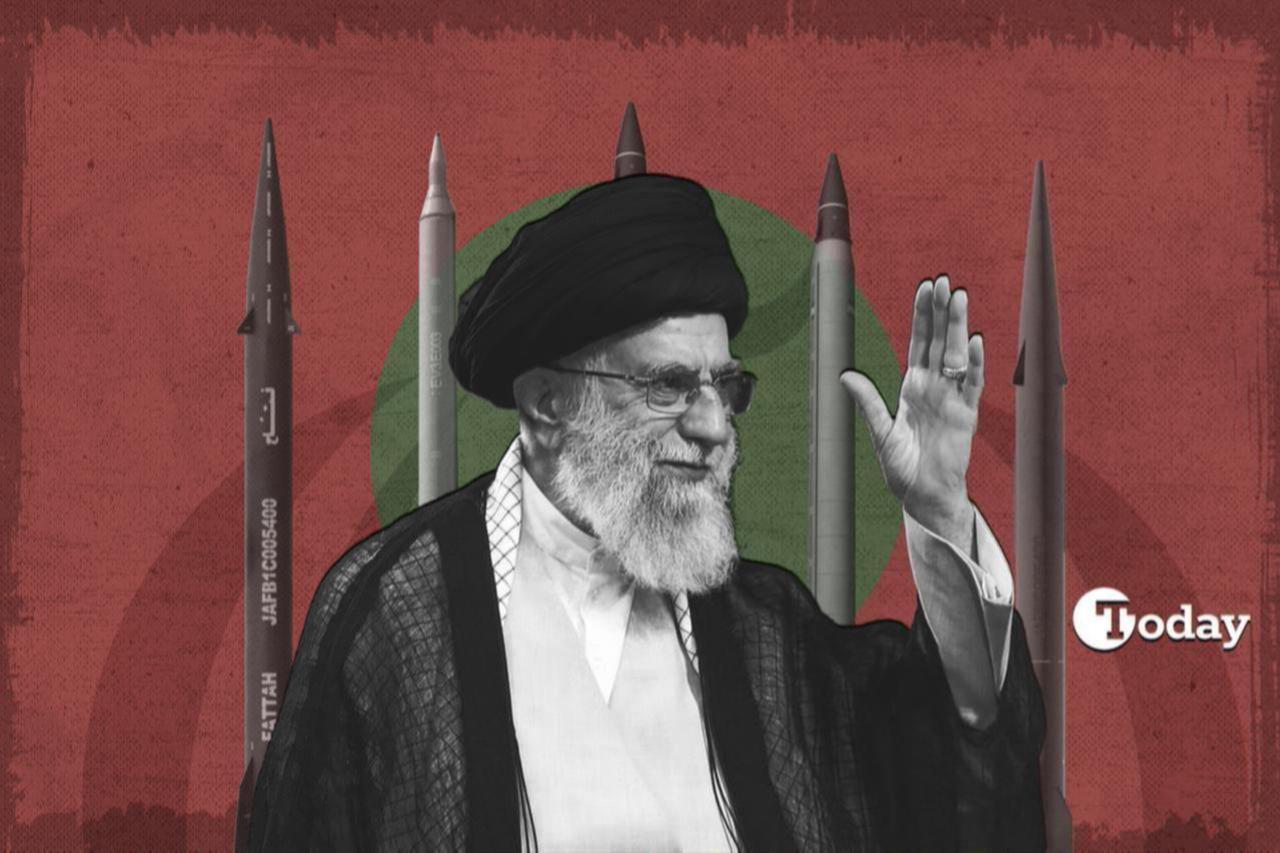

Absent massive U.S. airstrikes, the 12-Day War in June 2025 showed that while Israel’s air force is strong and agile, it cannot sustain a large-scale air campaign for over 10 days. We can therefore foresee that the regime in Iran will prevail, as it has since the 1979 revolution, even if the chaos further weakens the Islamic Republic domestically and internationally.

In this context, conflicting priorities have pulled Türkiye’s approach to Iran in different directions.

Deniz Karakullukcu has done a solid job here on Türkiye Today in laying out Ankara’s near-future geopolitical calculations regarding Iran: prioritizing stability without jeopardizing the privileged Turkish position as a NATO ally and regional transit hub.

From a historical standpoint, Türkiye’s baseline is to avoid another misguided U.S. military adventure with ill-defined political objectives as well as Iranian adventurism in its near abroad, as Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan’s Jan. 14 press conference revealed.

“We are opposed to a military intervention in Iran. Iran should solve its own authentic problems on its own. And the Iranian administration should stop denying certain things to its people and pursue peaceful policies toward regional countries,” Fidan said.

Recent history necessitates caution on Türkiye’s part. What political scientist Norman Finkelstein apparently said about America’s 20-year saga in Afghanistan—“If you ever feel useless, remember it took 20 years, trillions of dollars, and four U.S. presidents to replace the Taliban with the Taliban”—has also proven true in Iraq and Syria.

In Baghdad, pro-Iran political factions continue to wield great influence.

In Syria, the new government of Ahmed Al-Sharaa, whom the U.S. had treated as a “terrorist” during the civil war, has proven much more adaptive to working with regional and international partners compared to the U.S.-backed SDF.

As a result of those conflicts and U.S. policies, Türkiye ended up hosting millions of refugees and asylum seekers and footing the bill.

As this article went into press, it looked like U.S. President Donald Trump was standing down, not heeding the input of domestic allies such as Senator Lindsey Graham and his calls to “kill” Iran’s Supreme Leader, Syed Ali Khamenei.

For now, the Republican senator from South Carolina would have to remain content with posting “MIGA” (Make Iran Great Again) baseball caps with Cyrus Reza Pahlavi, the claimant to the Persian throne whose father, Mohammed Reza Shah, was toppled in Iran’s 1979 revolution.

Ankara will welcome U.S. forbearance.

Another conflicting dynamic that affects Türkiye’s position in Iran is the status of its Turkic kin in Iran. Iranian Turks—Azerbaijanis, Turkmens, Qashqais and others—constitute about 20% of Iran’s population.

Similarly, Iranian Kurds, who speak a dialect different than the Kurmanji Kurdish spoken among Turkish Kurds, make up another 10% of Iran’s population.

While many countries would try to stoke cross-border ethnic separatism, throughout history, successive Turkish governments have been careful not to play that card in Iran.

Not that it would work, especially among Iranian Turks. One of the puzzles of modern Iranian history is how it has been ruled consistently by Turkic leaders (probably including the Pahlavi dynasty), yet all have elevated Persian culture and language to a preeminent status, especially under Reza Shah, the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, and his son, Mohammed Reza Shah.

Supreme Leader Khamenei speaks Turkish and is Azerbaijani on his father’s side, while President Masoud Pezeshkian often refers to himself as a “Turk.” In fact, the leader of the 1979 revolution, Rouhollah Mousavi Khomeini, was one of the very few Iranian rulers without any known Turkic background in the last 500 years.

Overall, Iranian identity remains strong—not least because intermarriage among different ethno-linguistic groups has become much more common as Iran has undergone rapid modernization and urbanization since the early 20th century.

While leading nationalist thought leaders in Türkiye, such as Bahadirhan Dincaslan, occasionally state their hope that Iranian Azerbaijan might become an independent state, or better yet, assume a greater role that benefits the Turkic world. Thus, establishing a solid land bridge to the lands of Turkistan in Central Asia, reactions among Türkiye’s political class and the commentariat are much more cautious.

Many commentators have pointed out how little use Iranian Azerbaijanis, the largest group among Iranian Turks, have for the Islamic Republic (nor do they fondly remember the Pahlavi era), but many of them are still Iranian patriots and nationalists.

Devlet Bahceli, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s partner and head of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), called upon Iranian Azerbaijanis not to fall prey to what he sees as Western machinations to split Iran apart.

Bahceli’s call to the supporters of Tractor football club in Tabriz, one of the most fervent celebrants of Azerbaijani identity in Iran, was meaningful: “The tractors in Iran will not plow the corrupted fields of any externally imposed scheme or intrigue, will not be used as tools in a sinister game, will not abet dangerous instability, will not be complicit in wrongdoing, will not engage in aggression, and will not serve—nor even contemplate serving—as agents of imperialism,” per veteran Turkish journalist Murat Yetkin’s website, Yetkin Report.

At any rate, it would be hard to call upon Iranian Turks to secede but advise Iranian Kurds to not do so. In the latter case, the PKK’s Iranian branch, PJAK, which signaled its willingness to cooperate with Israel during the 12-Day War, will gain new ground that would jeopardize regional security in the long run.

A third conflicting factor in this picture is the close ties between the Turkish and American presidents.

So far, Erdogan has remained silent on events in Iran, perhaps unwilling to commit himself to a position that might put distance between himself and Trump, especially if the latter decides to attack Iran anyway.

There is too much at stake for Türkiye in the region beyond Iran—making sure Syria stays in one piece and hopefully prospers in the long term.

Similarly, ensuring that Palestinians in Gaza are no longer at the mercy of the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his extremist allies. Likewise, not allowing Greece, Greek Cyprus, and Israel to encircle Türkiye in the eastern Mediterranean is a chief geopolitical concern.

All of that requires Erdogan-Trump ties and Türkiye-United States relations to remain as strong and resilient as they can be.

Prudence on that front would also enable Türkiye to resolve the S-400 standoff and potentially receive U.S.-made weapon systems such as F-16s, F-35s, and possibly even Patriot air defense systems.