The flotilla, named Sumud—Arabic for steadfastness or perseverance—marks the largest such attempt to date. Organizers estimate that around 70 ships may eventually join the final leg of the journey.

The departure was accompanied by thousands of supporters chanting “Free Palestine” from the Spanish port, and with a widespread global solidarity movement behind the mission.

But only days into the voyage, Israel intercepted part of the Global Sumud in international waters, seizing several of the lead vessels.

Organizers stress the mission is still alive, noting that as long as not all ships are stopped, the remaining vessels will continue sailing toward Gaza.

On board are activists, doctors, lawyers, journalists, and politicians from 44 countries. They are carrying vital medical supplies, food, and water in an effort to deliver aid to the besieged enclave. The mission aims not only to provide relief but also to challenge the legality and humanitarian consequences of Israel’s naval blockade, enforced since 2007 and tightened further after October 2023.

The backdrop is dire: nearly two years of bombardment have left more than 63,000 Palestinians dead and famine conditions declared in parts of Gaza. International monitors warn that 93% of the enclave’s population now faces severe food shortages.

The first organized attempt to breach Israel’s blockade dates back to 2008. Activists from the Free Gaza Movement, formed during Israel’s war in Lebanon two years earlier, managed to reach Gaza’s shores with two small boats carrying humanitarian supplies. Between 2008 and 2016, the group launched 31 boats, though only a handful successfully evaded interception.

These early voyages highlighted both the possibilities and dangers of confronting Israeli restrictions by sea. Israel’s security posture hardened after 2010, ensuring that subsequent flotillas would face interception or military action before reaching Palestinian waters.

The deadliest and most politically consequential interception occurred on May 31, 2010. Israeli commandos stormed the Turkish vessel Mavi Marmara, part of the Freedom Flotilla, in international waters. The raid left 10 activists dead and dozens more injured.

The vessel carried more than 600 passengers and humanitarian aid, but its interception provoked an international outcry.

Relations between Türkiye and Israel plunged into crisis, while multiple U.N. bodies and human rights groups declared the assault a violation of international law. Amnesty International described the raid as an excessive and unjustified use of force against civilians.

Far from halting the solidarity movement, the Mavi Marmara became a symbol of resistance to the blockade, inspiring further attempts despite the risks.

The following year, the Freedom Flotilla Coalition prepared another large-scale mission involving over 10 ships and several hundred activists. Israel responded with a diplomatic campaign to prevent the vessels from sailing.

Under intense international pressure, Greece banned departures from its ports on security grounds. Only one ship, the French Dignité al-Karama, managed to leave, but it was intercepted in international waters and diverted to Ashdod. All passengers were detained and later deported.

In 2015, the lead ship of Freedom Flotilla III, the Marianne of Gothenburg, was intercepted roughly 100 nautical miles (160.9 kilometers) from Gaza. The activists aboard were detained and deported.

A year later, in October 2016, a women-only flotilla set sail to highlight the impact of the blockade on Palestinian women. The Zaytouna-Oliva was intercepted 35 miles off Gaza, and its 13 passengers—including parliamentarians and rights defenders—were detained before being deported.

These voyages broadened the scope of the flotilla movement, focusing not only on aid delivery but also on symbolic political messages of solidarity.

The 2018 campaign saw two main ships, the Al Awda (The Return) and Freedom, accompanied by support yachts, attempt to reach Gaza. Both were intercepted in international waters in late July and early August.

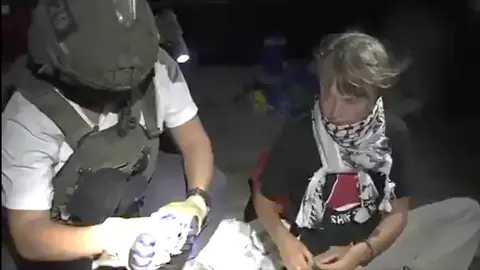

Activists reported being beaten and subjected to stun weapons during the operation. They were later arrested and deported.

The seizures drew criticism from human rights groups, which noted that the vessels carried humanitarian supplies.

With the escalation of war in Gaza after Oct. 7, 2023, new flotilla attempts emerged. In May 2025, the Conscience vessel was attacked by drones near Malta, forcing an emergency rescue.

In June 2025, the British-flagged Madleen was intercepted in international waters. Among its passengers were high-profile activists, including Greta Thunberg.

The ship, which carried medical supplies and infant formula, was seized, and its passengers were deported. Amnesty International condemned the operation as a violation of international law.

Another mission, the Handala ship, was intercepted in July 2025. Israel confiscated its cargo of medicines and baby formula, while detaining 21 activists and journalists.

These incidents show the continuity of Israel’s interception policy and the ongoing determination of activists to challenge it despite risks.

The legality of Israel’s blockade and interceptions remains contested. Under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, states cannot board foreign-flagged ships in international waters except under specific conditions, such as piracy, slave trade or lack of nationality.

Critics argue that Israel’s actions against civilian aid ships, such as the Madleen, fall outside these conditions.

Israel maintains that its blockade is a legitimate measure within the framework of armed conflict with Hamas. However, legal experts dispute whether such a blockade can be imposed in a non-international armed conflict.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has repeatedly highlighted the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of the blockade and ordered Israel to enable access for essential aid.

The San Remo Manual on naval warfare allows blockades under certain conditions, but not when they aim to starve civilians or cause disproportionate harm.

Human rights groups and several U.N. reports have concluded that the Gaza blockade violates these principles.

The Global Sumud Flotilla represents the most ambitious attempt to challenge the blockade in 17 years.

Backed by international organizations, political leaders, and cultural figures, it is designed to deliver aid and apply pressure on Israel to open a maritime humanitarian corridor.

Participants include prominent political voices like former Barcelona mayor Ada Colau and Portuguese MP Mariana Mortágua, alongside cultural figures such as actors Susan Sarandon and Liam Cunningham.

What sets this flotilla apart is its unprecedented scale and timing. Unlike earlier efforts, it unfolds during what international monitors describe as one of the gravest humanitarian crises in recent decades.

With famine conditions already declared in parts of Gaza, Sumud’s message is not only political but bound to survival itself.

Whether this flotilla will reach Gaza or face the same fate as its predecessors remains uncertain.

But its scale, symbolism and international visibility mark it as a significant moment in the history of maritime challenges to Israel’s blockade.