On Oct. 7, Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader Devlet Bahceli suggested that a parliamentary commission visit Imrali Island to meet face-to-face with imprisoned PKK ringleader Abdullah Ocalan.

Speaking at the party’s weekly parliamentary group meeting, Bahceli urged members of the Turkish Parliament's National Solidarity, Brotherhood, and Democracy Commission to “go to Imrali if necessary” and listen to Ocalan firsthand.

“Messages should be received directly,” he said, calling it a step toward transparency rather than negotiation.

The bigger issue he addressed was to press for Ocalan to issue a new, direct appeal to Syrian "PKK" offshoots—namely the YPG/SDG—urging them to abide by a previously negotiated “March 10 Agreement” with Damascus that envisions full integration into Syria’s state structures.

“While the PKK declared its dissolution, the SDG/YPG in Syria’s northeast has yet to obey Imrali’s call,” Bahceli said, referring to a Feb. 27 message attributed to Ocalan.

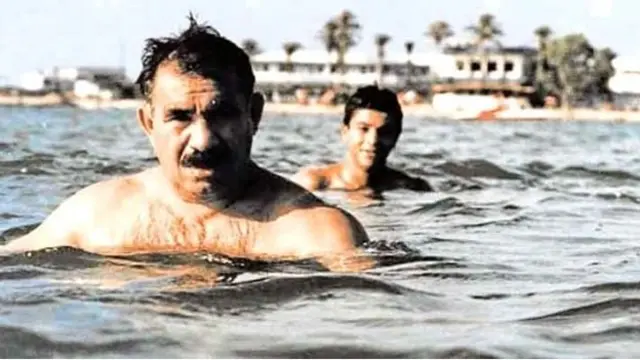

Bahceli’s reference to a Feb. 27 “Imrali call” points to Ocalan’s call on the organization to “lay down arms and disband.”

There has been much debate over whether this message applies only to the PKK in Türkiye.

DEM Party co-Chairs Tuncer Bakirhan and Tulay Hatimogullari stated at a press conference held in Parliament that the call made last spring was directed only at the PKK, not the YPG.

However, Bahceli's statements today appear to suggest otherwise. The call for the commission’s work to be guided not by domestic reconciliation but by regional alignment might point to a new start in the ongoing process.

The YPG's entire autonomous administration model, grand strategy, and founding principles are based on the foundations laid by ringleader Ocalan in the 1980s and 1990s.

The organization's current leader, Mazloum Abdi, is a figure who was trained and raised by Ocalan himself as well.

Tensions across northern Syria have complicated the implementation of the March 10 Agreement between the SDG and Damascus, which calls for integrating northeastern institutions and military forces into the Syrian state.

While Washington backed the cautious steps toward normalization, the process remains stalled.

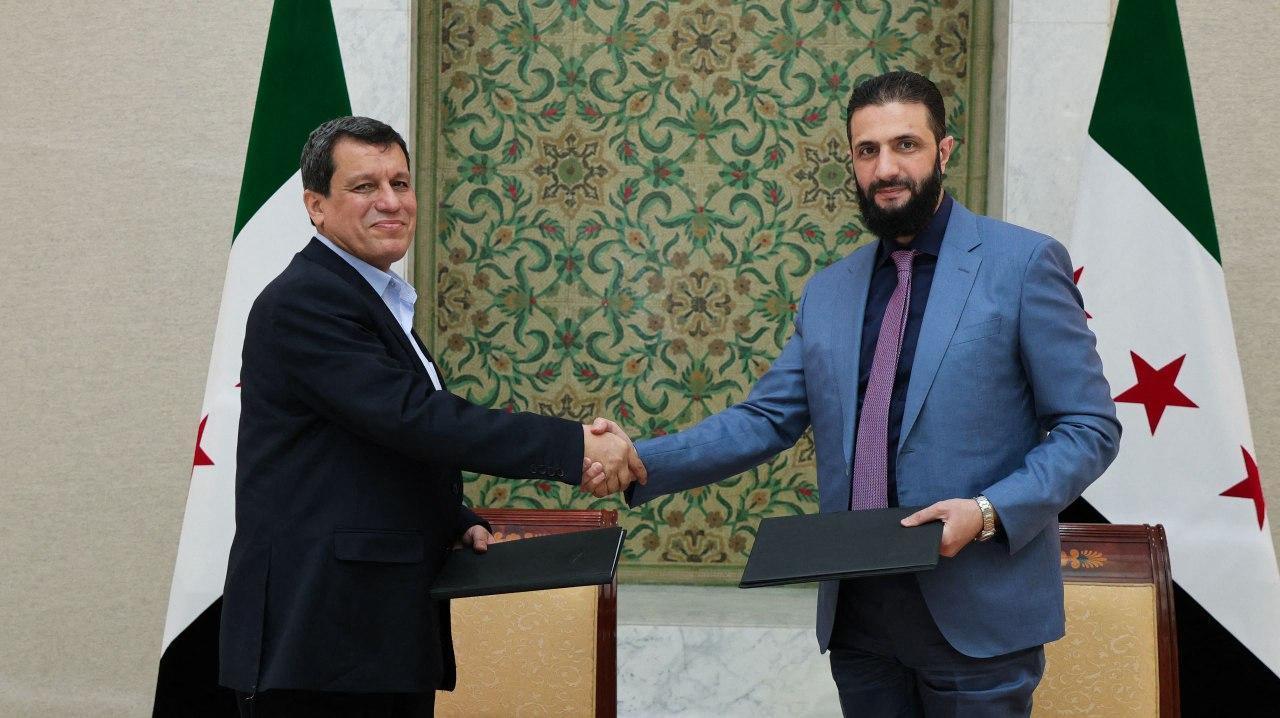

Last week, U.S. envoy Tom Barak met with SDG commander Abdi and Ilham Ahmed in Ankara to discuss the integration plan.

Soon after the meeting, Abdi signaled tentative openness to broader inclusion within Syria’s political structure, a gesture interpreted by some as a green light for renewed coordination.

However, internal divisions remain. Negotiations between the SDG and Damascus’s Defense Ministry reportedly faltered when new administration officials balked at SDG demands for ministries in defense and security institutions.

Damascus doesn’t want to concede military authority, and Türkiye doesn’t want to see the terror organizations gain legitimacy.

That leaves the SDG in limbo and gives Ankara reason to reassert its influence through political channels like Imrali.

Bahceli’s proposal was met with quiet approval from some within the presidential orbit. Presidential advisor Mehmet Ucum reiterated that the Imrali visit would be purely procedural, calling it a “listening” mission.

He stressed that “no negotiation” would occur, noting that parliamentary commissions regularly visit correctional facilities—including high-security prisons—as part of standard oversight.

Bahceli’s suggestion echoes a long-standing demand by the Kurdish-leaning Peoples' Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), which has repeatedly called for Parliament to listen to Ocalan as part of any meaningful discussion on Türkiye’s terror-free project.

For Bahceli, this integration represents a test case: if certain rebel factions in Syria can be pressed, through political and moral channels, to return under state authority, Ankara’s claim to a “terror-free region” could gain new weight beyond its own soil.

Türkiye and the new Syrian administration have long preferred peaceful diplomacy over military solutions against this large rebel group.

However, the organization is doing everything in its power to resist efforts to draw it into peaceful politics, including calls from the U.S. ambassador to Türkiye.

If Bahceli's new initiative is implemented by Ocalan, it will be shared as a message from the organization's founder that the organization has lost its validity.