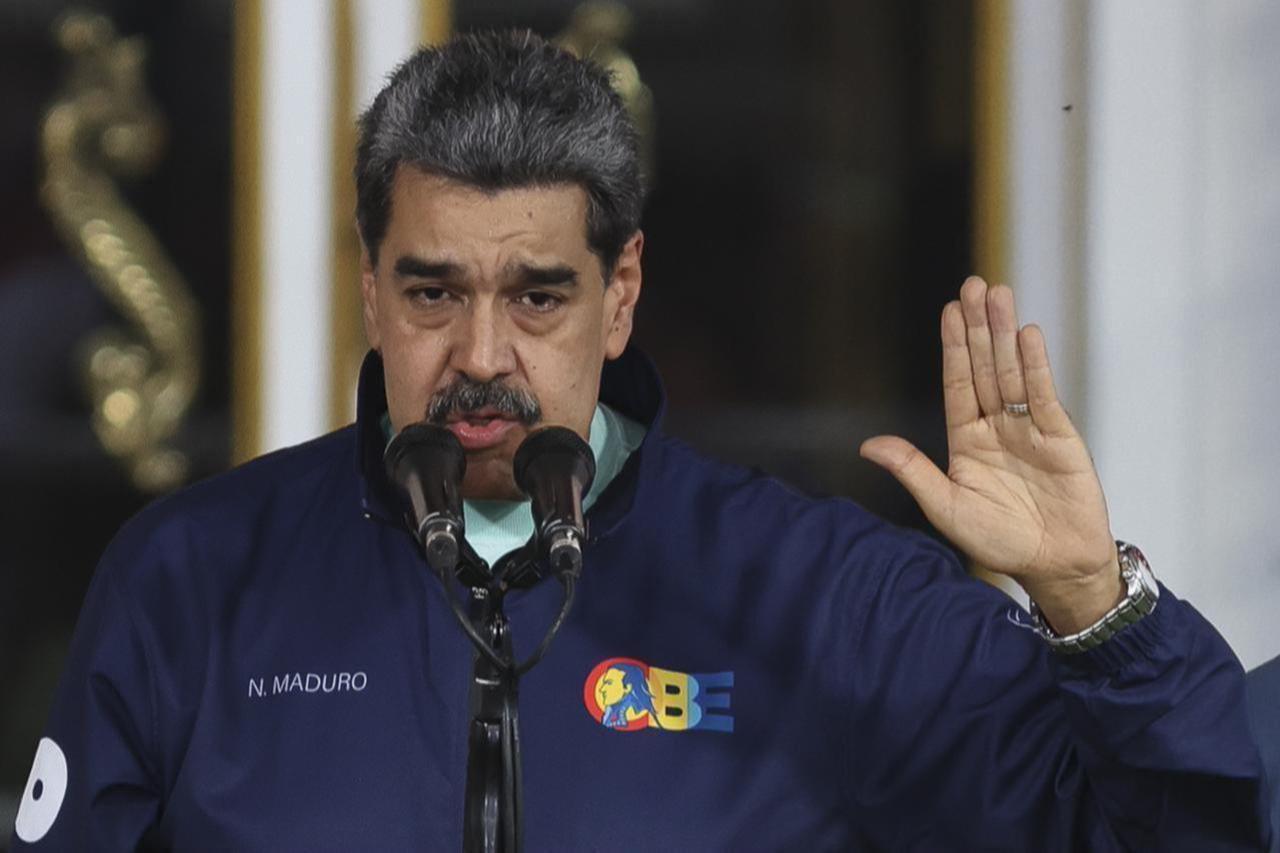

The US military's seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro in January has opened a rift among Western officials over whether the operation strengthened or undermined the international order, with allied governments struggling to reconcile the removal of an authoritarian leader with the manner in which it was carried out.

Speaking on a panel at the Munich Security Conference on Saturday, US, European and Latin American officials offered starkly different assessments of the Jan. 3 operation, reflecting a broader unease within the Western alliance over the Trump administration's unilateral approach.

US Sen. Ruben Gallego, a Democrat on the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, captured the tension most bluntly. He said he was "glad he's gone," referring to Maduro, but warned that the consequences of the operation extend well beyond Venezuela.

"The violation of rules-based orders from this should really concern everyone that actually lives, dies and prospers by the rules-based order," Gallego said, pointing to the lack of broad international backing for the move.

The senator's remarks underscored a growing concern among lawmakers and diplomats that Washington's willingness to act outside multilateral frameworks, even against widely condemned governments, risks eroding the very norms the United States has long championed.

Costa Rica's foreign minister, Arnoldo Andre Tinoco, offered a more supportive view, shaped largely by his country's frontline experience with Venezuelan displacement. He noted that a significant share of the roughly eight million Venezuelans who have fled political turmoil in Caracas passed through Costa Rica, a migration wave that has reshaped the Central American nation's politics and public services.

Tinoco said a poll conducted after Maduro's removal found that 84 percent of Costa Ricans approved of the US action, a figure that reflects the depth of public frustration with the humanitarian spillover from Venezuela's crisis.

He also outlined shared priorities with Washington, describing ongoing cooperation on migration, organized crime and narcotics trafficking, as well as concerns about Chinese investment in security-sensitive areas. "We are struggling against organized crime and narco trafficking with the support of the US," he said.

Portuguese Foreign Minister Paulo Rangel struck perhaps the most carefully calibrated tone of the session, acknowledging both the legal breach and the practical impossibility of restoring Maduro to power.

Portugal has deep ties to Venezuela through an expatriate community of roughly half a million people, giving Lisbon a direct stake in the country's stability. Rangel stressed that his government never recognized Maduro's disputed election, but that respect for international law and the UN Charter remains fundamental.

Yet he argued that the path forward cannot simply mean returning Maduro to the presidency. "There was a break, that international law was broken, but the way to reintegrate, to restore international law, is not to bring again Maduro," Rangel said, adding that the situation "probably is not so white and black as people normally say."

The US operation on Jan. 3 set off a rapid chain of events inside Venezuela. Delcy Rodriguez was sworn in as interim president, the government enacted changes to Venezuela's flagship oil law, and some political prisoners were released, though the full scope of the transition and its permanence remain subjects of intense international scrutiny.

The Munich Security Conference, held annually in the Bavarian capital, has long served as a barometer of transatlantic relations and global security debates. This year's discussion on Venezuela highlighted the degree to which the operation has forced allied capitals to confront uncomfortable questions about sovereignty, legitimacy, and the limits of the rules-based order.

Venezuela has been mired in political and economic crisis for more than a decade. Under Maduro, who succeeded Hugo Chavez in 2013, the country experienced hyperinflation, the collapse of public services, and one of the largest displacement crises in Latin American history.

Western governments, including the United States and the European Union, refused to recognize Maduro's claim to a second term following the disputed 2018 presidential election, and many later backed opposition leader Juan Guaido's claim to the presidency, though that effort ultimately failed to dislodge Maduro from power.