Türkiye has left behind a quarter of a century since the 2001 economic crisis, the most severe financial turmoil in the Republic’s history that led to a deep contraction, widespread uncertainty, and forced sweeping reforms that reshaped the country’s economic direction.

The crisis, which erupted in February 2001 following a political dispute at the highest levels of government, quickly spiraled into a full-scale financial collapse, exposing deep structural weaknesses in the banking sector, fiscal policy, and monetary management.

Long before the collapse, Türkiye’s economy was characterized by chronically high inflation, recurring political instability, and a financial system increasingly exposed to structural vulnerabilities.

Throughout the 1990s, inflation remained persistently elevated, frequently exceeding 60% annually and at times rising above 80%. It peaked at 125.5% in 1994 during a previous financial crisis and remained extremely high at 68.8% by the end of 1999.

Public finances also deteriorated significantly. The public sector borrowing requirement reached 24.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1999, while net public debt rose to approximately 61% of GDP, driven largely by heavy reliance on short-term, high-interest domestic borrowing. Servicing this debt consumed a substantial share of government revenues, deepening fiscal fragility and increasing the economy’s exposure to interest rate volatility and refinancing risks.

In response, authorities launched an International Monetary Fund (IMF)-backed disinflation program in December 1999 under a $4 billion standby agreement, later expanded to around $11 billion with additional international support.

The program aimed to reduce inflation to 25% by the end of 2000 and place the economy on a path toward sustained price stability, supported by fiscal tightening and a pre-announced exchange rate framework.

Initially, the program delivered measurable improvements in key macroeconomic indicators. Annual inflation declined sharply from 68.8% in 1999 to 39% in 2000, reflecting the impact of tighter fiscal policy and the exchange rate-based stabilization strategy.

Borrowing costs also fell significantly, easing pressure on public finances. The Treasury’s average weighted interest rate in government bond auctions declined from 128% in January 1999 to 36.1% in January 2000, a drop of nearly 90 percentage points within a year that helped reduce debt servicing pressures.

Improved policy credibility was also reflected in stronger external financing. Capital inflows accelerated rapidly, with net capital inflows reaching at least $12.5 billion in the first 10 months of 2000, as foreign investors increased exposure to Turkish government securities and financial markets amid rising confidence in the IMF-backed stabilization program.

By 2000, signs of strain began to emerge as concerns over banking sector solvency and fiscal sustainability fueled rising market nervousness.

In November 2000, Türkiye experienced a severe liquidity crisis after foreign investors began withdrawing funds, forcing the central bank to defend the currency regime aggressively. Overnight interest rates surged to over 2,000% at peak stress, laying bare deep vulnerabilities in the banking system and triggering acute funding shortages at several financial institutions.

This fragile equilibrium ultimately collapsed on Feb. 19, 2001, during a National Security Council meeting, where a public dispute between President Ahmet Necdet Sezer and Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit triggered a sudden loss of confidence in the government’s ability to manage the crisis.

Speaking to reporters after the meeting, Ecevit said, “The President displayed an unprecedented behavior that has no place in our state traditions,” publicly confirming tensions at the highest level of the state and alarming financial markets.

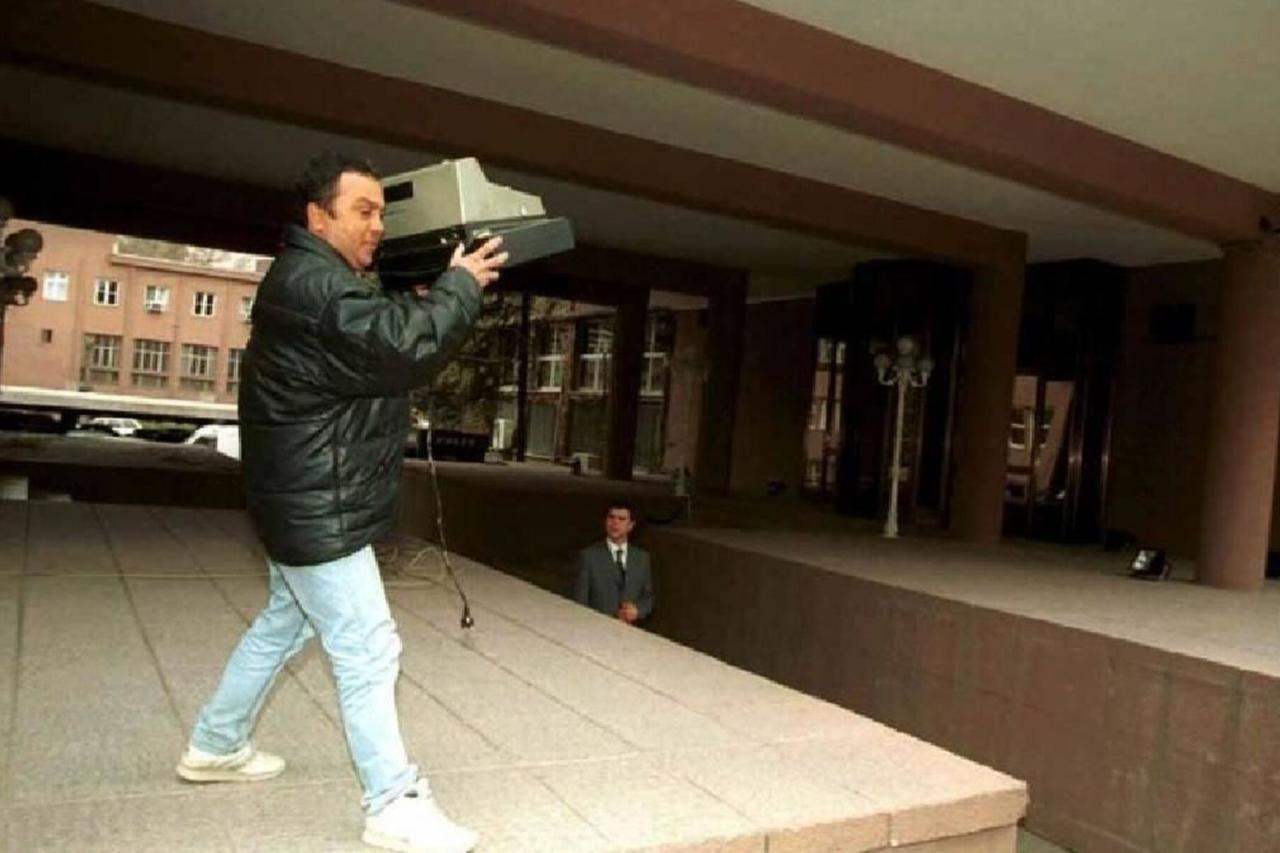

Investors reacted immediately to the political shock. Following Ecevit’s remarks describing the meeting as a serious crisis, Borsa Istanbul plunged amid intense panic selling, with the benchmark index closing down 14.6%, one of the steepest daily losses on record. Losses deepened in the following days, and by Feb. 21, also known as "Black Wednesday," the index fell a further 18.1%.

Financial markets came under extreme stress as liquidity evaporated across the system amid accelerating capital outflows. Financial markets came under extreme stress as liquidity evaporated across the system. Overnight repo interest rates surged to as high as 7,500%, while overnight interbank rates climbed to around 6,200%.

Within days, authorities were forced to abandon the crawling peg and allow the lira to float freely, marking the beginning of the full-scale financial crisis.

The decision to float the lira triggered an immediate and severe economic shock. The currency depreciated by nearly 40% against the U.S. dollar within days, sharply increasing the cost of imports and foreign currency debt.

Inflation, which had declined under the stabilization program, surged again, climbing from 39% in 2000 to 68.5% in 2001, eroding household purchasing power and reversing earlier gains in price stability.

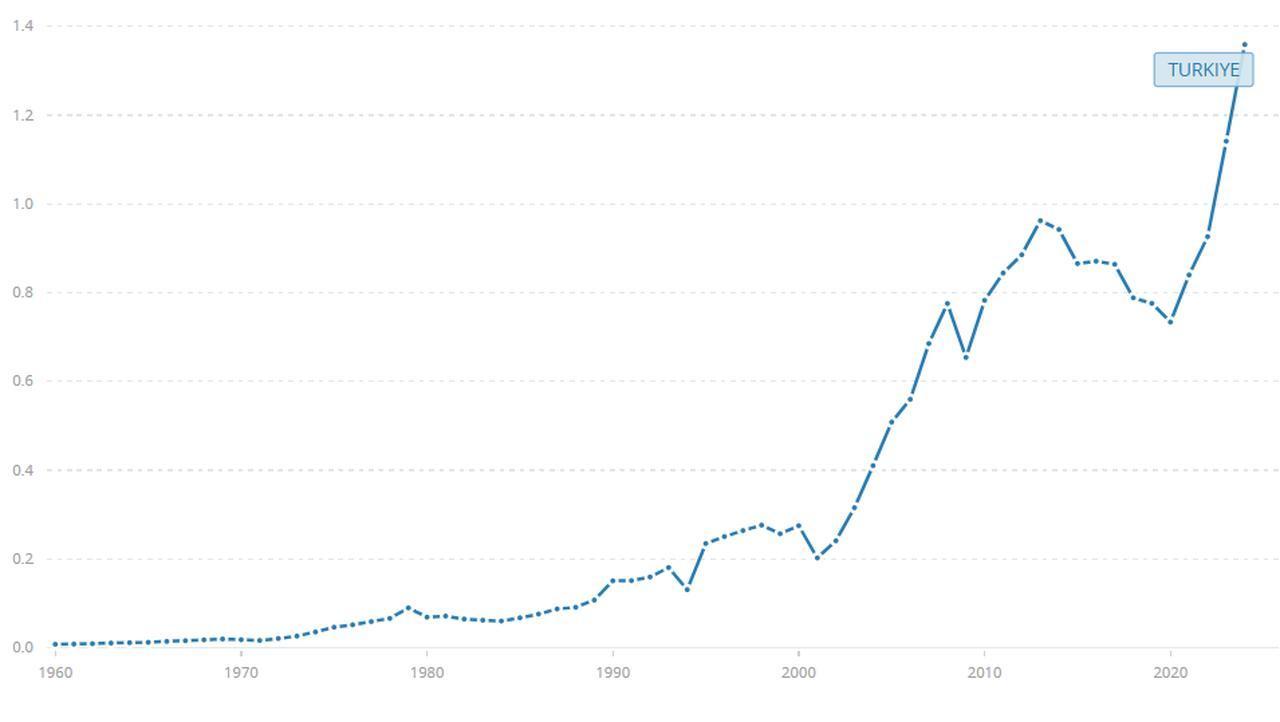

The broader economy contracted sharply. Türkiye’s gross domestic product shrank by 5.7% in real terms in 2001, representing one of the deepest recessions in the country’s modern history. In dollar terms, the impact was even more severe, with GDP falling from $273 billion in 2000 to around $200 billion in 2001, a decline of nearly 27% as the sharp depreciation of the Turkish lira significantly reduced the economy’s value.

Industrial production fell significantly, while thousands of businesses—particularly small and medium-sized enterprises—were forced to close or scale back operations amid collapsing domestic demand and tightening credit conditions.

The crisis also had profound social consequences. Unemployment rose rapidly, increasing from 6.5% in 2000 to around 10.3% in 2002, while real wages declined sharply due to inflation and economic contraction. Poverty levels increased, and many households experienced a sudden deterioration in living standards as job losses and rising prices took hold.

Public debt dynamics worsened dramatically in the immediate aftermath. Net public debt rose from around 61% of GDP in 1999 to 93.3% of GDP by 2001, driven by currency depreciation, banking sector rescue costs, and recession-related fiscal pressures.

In response to the crisis, authorities launched a comprehensive reform program under the leadership of then-Economy Minister Kemal Dervis, who was appointed in March 2001. The reform agenda focused on restoring macroeconomic stability, strengthening institutional credibility, and addressing structural weaknesses that had contributed to the collapse.

Key measures included granting greater operational independence to the Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye, restructuring and recapitalizing the banking sector, strengthening financial supervision, and implementing strict fiscal discipline.

These reforms, supported by a new IMF program worth $16 billion, helped stabilize financial markets and restore investor confidence over time.

Inflation fell to 29.7% by 2002 and declined to single digits by 2004, while economic growth rebounded strongly, with GDP expanding by 6.2% in 2002 and 5.3% in 2003. Public debt ratios also declined steadily, falling from nearly 90% of GDP at the peak of the crisis in 2001 to around 70% by 2003 and below 60% by 2005.

The crisis ultimately marked a turning point in Türkiye’s economic framework, laying the institutional foundation for the period of strong growth and relative macroeconomic stability that followed in the mid-2000s.

Economists widely regard the 2001 crisis as a structural turning point that reshaped Türkiye’s economic foundations. While the collapse caused deep economic damage in the short term, it also forced sweeping reforms that transformed monetary policy, strengthened financial regulation, and restored institutional credibility, laying the groundwork for a more stable macroeconomic framework in the years that followed.

Turkish economist Mahfi Egilmez describes the post-crisis transformation as one of the most significant structural shifts in the country’s modern economic history. "After the 2001 crisis, Türkiye implemented banking reforms,” he said, emphasizing the scale of institutional change. "This was the most important structural reform we carried out in the past 40 years, and it was not done voluntarily but out of necessity created by the crisis."

Similarly, economist and former Central Bank chief economist Hakan Kara has characterized the crisis as a decisive turning point in Türkiye’s monetary policy regime. In his academic work, Kara wrote that "the post-2001 period represents a fundamental regime change in Turkish monetary policy," noting that the reforms enabled the central bank to focus on price stability as its primary objective and strengthened policy credibility.

Kara also asserts that the post-crisis period lays the foundation for "a period of rapid disinflation and strong economic growth," supported by improved institutional discipline, stronger policy frameworks, and renewed investor confidence. According to his analysis, the structural reforms implemented after the crisis played a critical role in stabilizing inflation, restoring financial stability, and enabling Türkiye to transition to a more resilient and rules-based economic system.

However, the structural reforms implemented during this period also paved the way for Türkiye’s strong economic performance in the years that followed. Beginning in 2002 and accelerating after 2004, the economy entered a sustained expansion phase supported by declining inflation, improved fiscal discipline, and renewed investor confidence.

Annual economic growth averaged around 7% between 2002 and 2007, making Türkiye one of the fastest-growing emerging markets during that period. Inflation, which had remained chronically high for decades, fell into single digits by 2004 for the first time in more than 30 years.

The post-crisis transformation also fundamentally changed the structure of economic policymaking. The adoption of a floating exchange rate regime, combined with an independent central bank focused on price stability, reduced vulnerability to speculative attacks and external shocks.