Africa’s oldest known cremation has been identified in northern Malawi, where researchers found a 9,500-year-old funerary pyre that points to unexpectedly complex Stone Age mortuary rituals among early hunter-gatherers.

The discovery, reported in the journal Science Advances, extends Africa’s cremation record by several thousand years and shows that fire, place, and careful preparation could be brought together in a single, highly structured burial event.

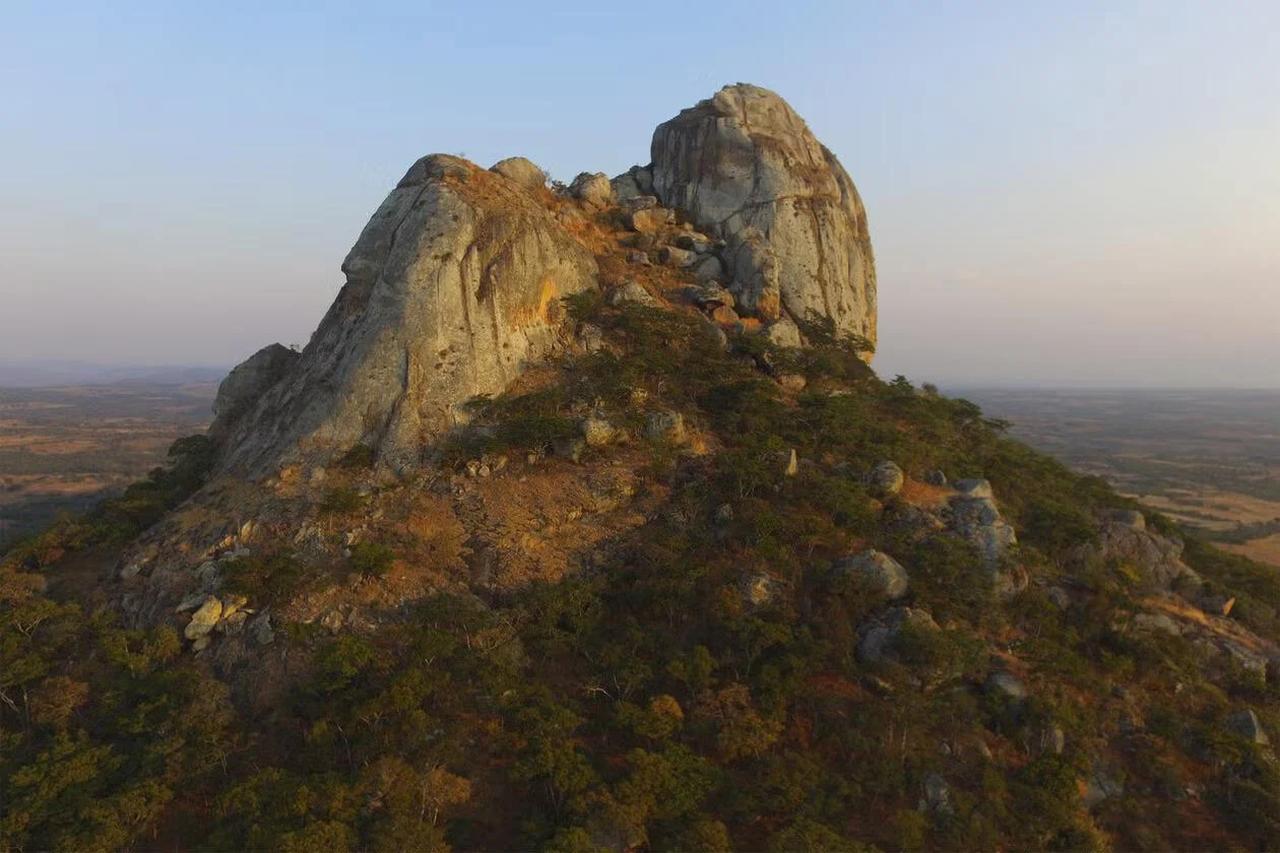

The cremation was uncovered at a site known as Hora 1, located beneath a rock shelter at the base of Mount Hora. The mountain is described as a granitic inselberg, meaning a steep, isolated rocky hill rising sharply from a flatter plain. Excavations indicate the wider area was inhabited as early as 21,000 years ago, while it also served as a burial ground from roughly 16,000 to 8,000 years ago.

Against that backdrop, the newly identified cremation stands out because burials at Hora 1 had otherwise involved complete inhumations, a term used for full-body burials in the ground. The 9,500-year-old pyre involved only one individual and marked a clear break from the established practice at the site.

Researchers recovered around 170 fragments of human bone from an extensive ash deposit. The remains were assessed as belonging to a short adult female, aged between 18 and 60. Patterns of burning and fracturing suggest the body was placed on the pyre soon after death, before decomposition had started.

The bones also carried cut marks on the limbs, which the researchers interpreted as signs of deliberate defleshing or dismemberment before the burning. At the same time, the lack of teeth and skull fragments suggested the head may have been removed ahead of cremation.

Reconstructing how the pyre was built, the team concluded it would have taken communal effort. They estimated that at least 30 kilograms of wood and grass were gathered as fuel, and microscopic evidence pointed to active fire management, with additional fuel being put on to keep temperatures above 500 degrees Celsius.

Stone tools found within the ash layers were seen as possibly being placed there during the burning as a ritual act.

The study also drew attention to activity at the exact location over time. Evidence suggested large fires had been lit there several centuries before the cremation, and that people later came back to set further fires directly over the pyre for several centuries afterward.

Even though no additional cremations were identified at the spot, the repeated use of the same place was taken to suggest it stayed in collective memory as a location with ongoing ritual importance tied to the landscape.

Why this one woman was treated in such a labor-intensive and distinctive way remains unclear in the study’s account.

Even so, the researchers said the finding makes it clear that early African foragers could carry out symbolic and complex mortuary practices, bringing together fire control and a meaningful setting to mark death in ways not previously recognized for hunter-gatherers of this age.