Egypt has brought to light a major archaeological site in South Sinai dating back around 10,000 years, uncovering what officials describe as one of the region’s most significant rock art landscapes and opening up a long, continuous record of human presence in the area.

According to Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, an Egyptian archaeological mission identified the site at the Umm Irak Plateau, where carvings and pigment drawings stretch across millennia. Officials characterized the plateau as an “open-air museum of rare carvings and drawings,” pointing to the scale and diversity of the material that has come to light.

The Umm Irak Plateau preserves what authorities describe as a layered visual archive, tracing human activity from prehistoric communities to the early Islamic period. Rock art, a term used to describe images carved or painted onto natural stone surfaces, often serves as one of the few surviving records of early societies that left behind no written texts.

Tourism and Antiquities Minister Sherif Fathy said the discovery provides fresh evidence of the succession of civilizations that passed through Sinai, underscoring the peninsula’s role as a crossroads over thousands of years.

Hisham el-Leithy, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, indicated that the wide chronological and technical range of the engravings sets the site apart. He described it as ranking among the most important rock art locations discovered recently, effectively functioning as a natural open museum.

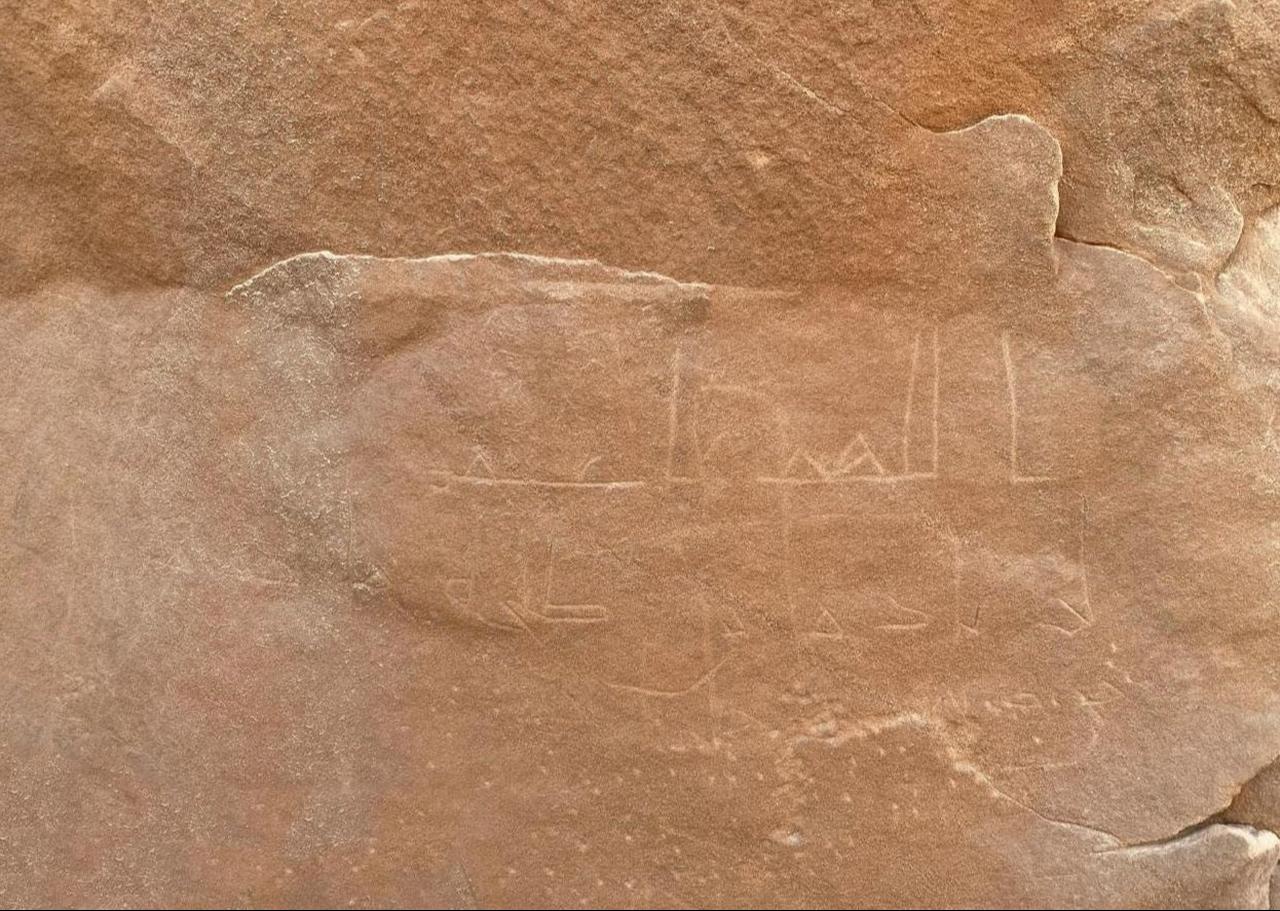

At the heart of the discovery lies a rock shelter extending more than 100 meters along the eastern side of the plateau. A rock shelter refers to a shallow cave-like formation created naturally by erosion, often used by early communities for protection and habitation.

Mohamed Abdel-Badie, head of Egypt’s antiquities sector, explained that the plateau sits within a distinctive sandy area that was likely used across eras as a lookout point, gathering place and rest stop. Within the shelter, archaeologists documented red and gray pigment drawings depicting animals and symbolic forms.

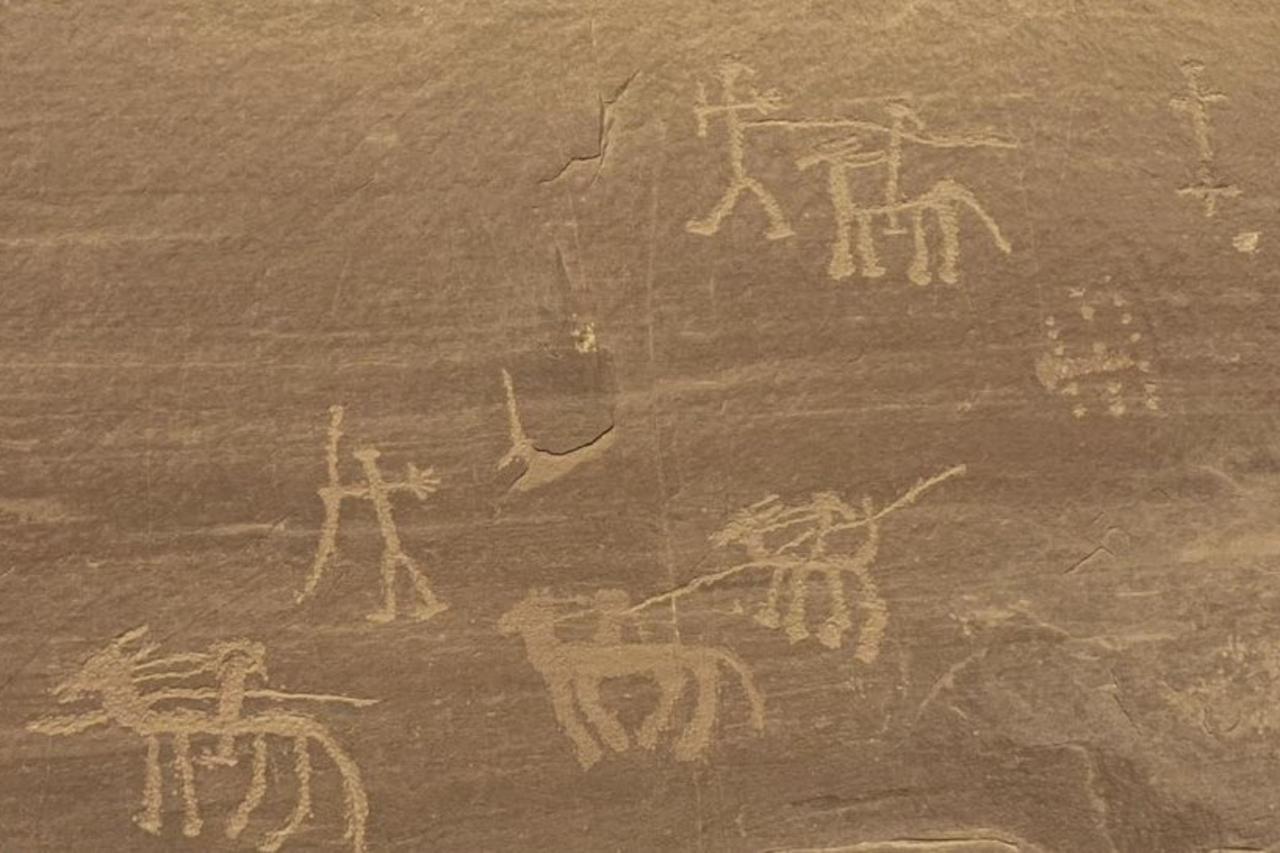

The oldest images date back roughly between 10,000 B.C. and 5,500 B.C., portraying early lifestyles such as hunting ibex with bows and the use of hunting dogs. Ibex are wild mountain goats native to the region, frequently represented in prehistoric art across the Middle East. Later carvings introduce horses, camels and human figures carrying weapons, while Arabic inscriptions indicate that the site continued to be used into the early Islamic period.

Taken together, these layers trace a long arc of human adaptation, from prehistoric hunter groups to societies familiar with mounted transport and written language.