In the Ottoman Empire, jewelry was not a footnote to fashion but a language of power.

Jewelry was worn by sultans, courtiers, diplomats, and the women of the imperial harem. Jeweled objects signaled rank, wealth, belief, and political presence. They were not simply decorative. They were statements, carefully constructed and strategically displayed.

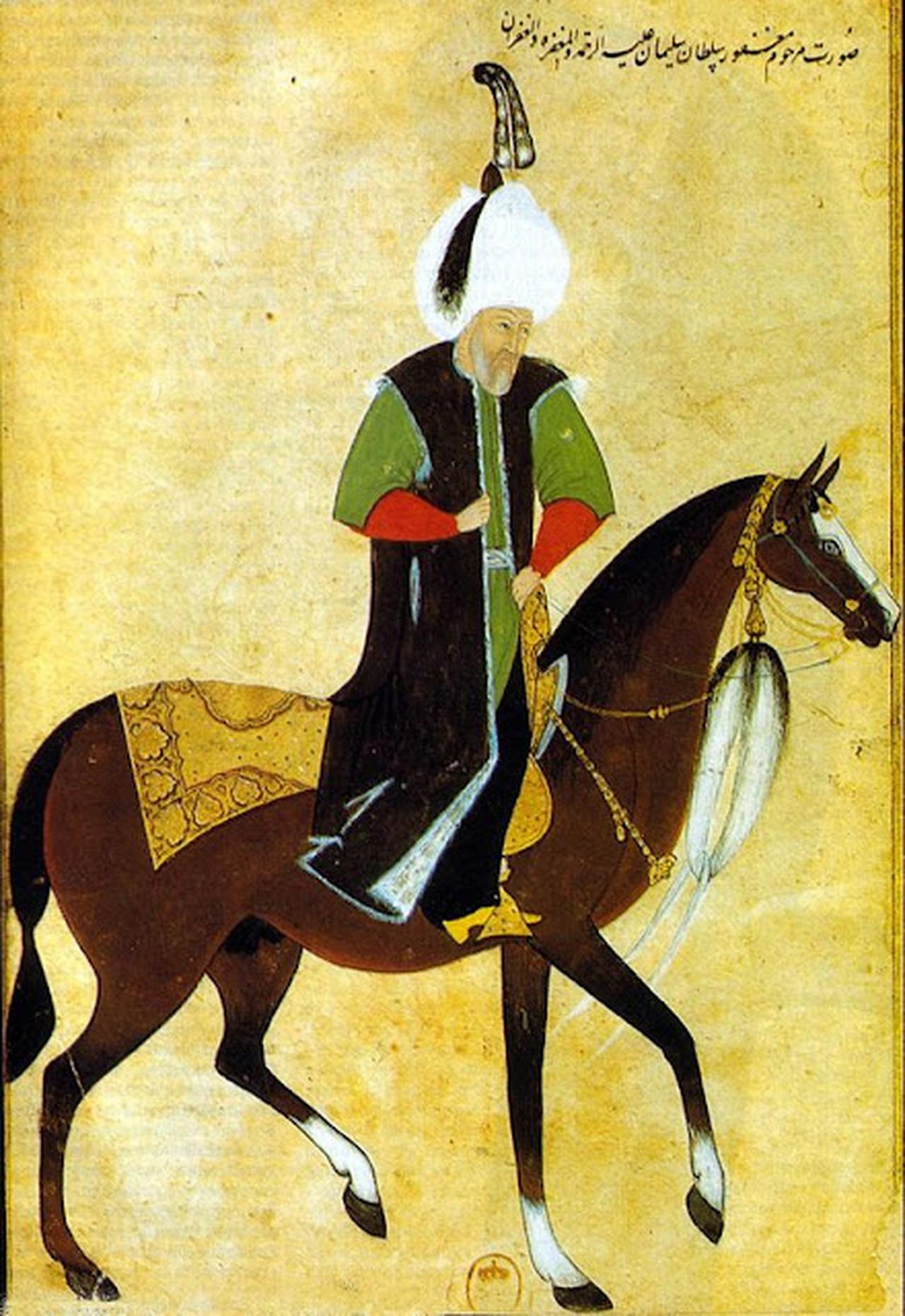

From jeweled swords and daggers to belts, aigrettes, and pearl-laden necklaces, Ottoman jewelry transformed the body into a stage. Power was not only exercised, it was styled.

Jewelry in the Ottoman world functioned as both personal adornment and a political tool.

Jeweled objects were used in diplomacy, bestowed as honors, and displayed during court ceremonies and processions. Even horses were outfitted with jeweled aigrettes, reinforcing the spectacle of imperial authority.

Within the palace, artisans produced not only wearable pieces but also richly decorated objects such as; Quran cases, ceremonial cups, book covers, swords, daggers, and personal accessories. These creations blurred the boundary between ornament and instrument, embedding luxury into everyday and ceremonial life alike.

As Prof. Gul Irepoglu noted that jeweled objects became inseparable from both religious and secular rituals. In the Ottoman court, adornment was part of governance.

Ottoman jewelry emerged from a uniquely layered cultural environment. Drawing on Byzantine, Persian, Arabic, European, and Anatolian traditions, it developed a style that was richly hybrid. Istanbul’s role as a crossroads between Europe, Asia, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea helped shape a jewelry culture that absorbed and transformed multiple influences.

Unlike many European traditions that favored strict symmetry and uniform metals, Ottoman jewelers embraced variety. Multiple metals might appear in a single piece. Natural stone shapes were often preserved rather than forced into perfect faceting. Irregularity was not corrected but celebrated.

This approach produced jewelry that felt organic, expressive, and visually complex, reflecting the empire’s broader cultural synthesis.

Gemstones in Ottoman jewelry were selected not only for beauty, but for symbolic and spiritual significance. Emeralds were associated with wisdom and love. Rubies with vitality and protection. Pearls with purity and calm. Jade with healing. Agate with grounding and balance.

Diamonds were often used as supporting stones, framing and enhancing the power of a central gem rather than dominating the design.

Jewelry, in this context, became a form of belief made visible and a system where aesthetics and spirituality were closely intertwined.

The 16th century marked the peak of Ottoman jewelry production. Court records from 1526 indicate that up to 90 jewelers worked in the service of the emperor.

Gold, emeralds, rubies, pearls, and diamonds were used not only for fashion jewelry, but also for utilitarian and ceremonial objects.

Artisans incorporated a wide range of materials, including ivory, mother-of-pearl, glass, leather, horn, bone, and wood.

Techniques such as filigree, inlaying, engraving, embossing, and chasing were widely practiced. Jewelry production took place both within the palace and in workshops across the empire.

Natural motifs dominated design. Tulips, roses, violets, birds, butterflies, and bees appeared frequently, transforming jewelry into wearable gardens. Movement was also a design feature.

Pins such as the “titrek” and “zenberekli” were crafted to tremble and shimmer with motion, animating the wearer.

For Ottoman women, jewelry carried both aesthetic and economic meaning.

Gold bangles, in particular, functioned as portable wealth, adornment that could be converted into cash when needed. Jewelry formed part of dowries and was passed down across generations, reinforcing its role as financial security.

Jewelry also marked life events. Pieces were given for marriages, religious festivals, and circumcision ceremonies. A necklace or bracelet could signal both celebration and stability.

Elite women wore chokers, long pearl strands, and necklaces strung with gold coins. Belts adorned with diamonds, rubies, turquoise, and emeralds were worn at the waist or hips, serving as both fashion statements and status markers.

Hafize Sultan was described as wearing pearls that reached her knees, along with emerald chains and an exceptionally large diamond, an image that underscores how jewelry functioned as visual spectacle within court life.

Among the most distinctive Ottoman jewelry forms were aigrettes, which are jeweled ornaments worn on turbans. They symbolized rank and authority and were worn by both sultans and prominent women of the harem.

Aigrettes were also given as prestigious gifts and worn by horses during ceremonial processions.

Pins played a major role in women’s headdresses and hairstyles. Often decorated with floral and natural motifs, these pieces added movement and visual rhythm, enhancing both hairstyle and overall dress.

Earrings ranged from simple pearl drops to elaborate multi-part designs. Rings, including signet rings and gem-set styles, served both decorative and functional roles, often linked to identity and status.

By the 19th century, political reforms and increased exposure to Europe brought new stylistic influences.

French and Austrian-inspired forms, including lockets, diamond tiaras, and naturalistic floral designs, entered Ottoman jewelry culture.

Rather than replacing traditional motifs, these European elements blended with Ottoman symbols such as the crescent.

Armatli Koroglu et al. highlight that jewelers in Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar adapted to this hybrid aesthetic, producing pieces that appealed to both Ottoman and European tastes.

The result was a layered visual language, traditional and modern, local and international, in addition, it was reflecting a changing empire.

Ottoman jewelry was never simply about luxury. It was about identity, power, belief, and performance.

Each piece functioned as both adornment and message, worn on the body but speaking far beyond it.

Today, gold necklaces, bracelets, and earrings remain central to Turkish jewelry culture. Contemporary designers continue to draw from Ottoman motifs, craftsmanship, and visual richness, translating historical aesthetics into modern forms.

In this sense, Ottoman jewelry is not confined to museum cases. It remains a living language and one in which history is worn, not just remembered.