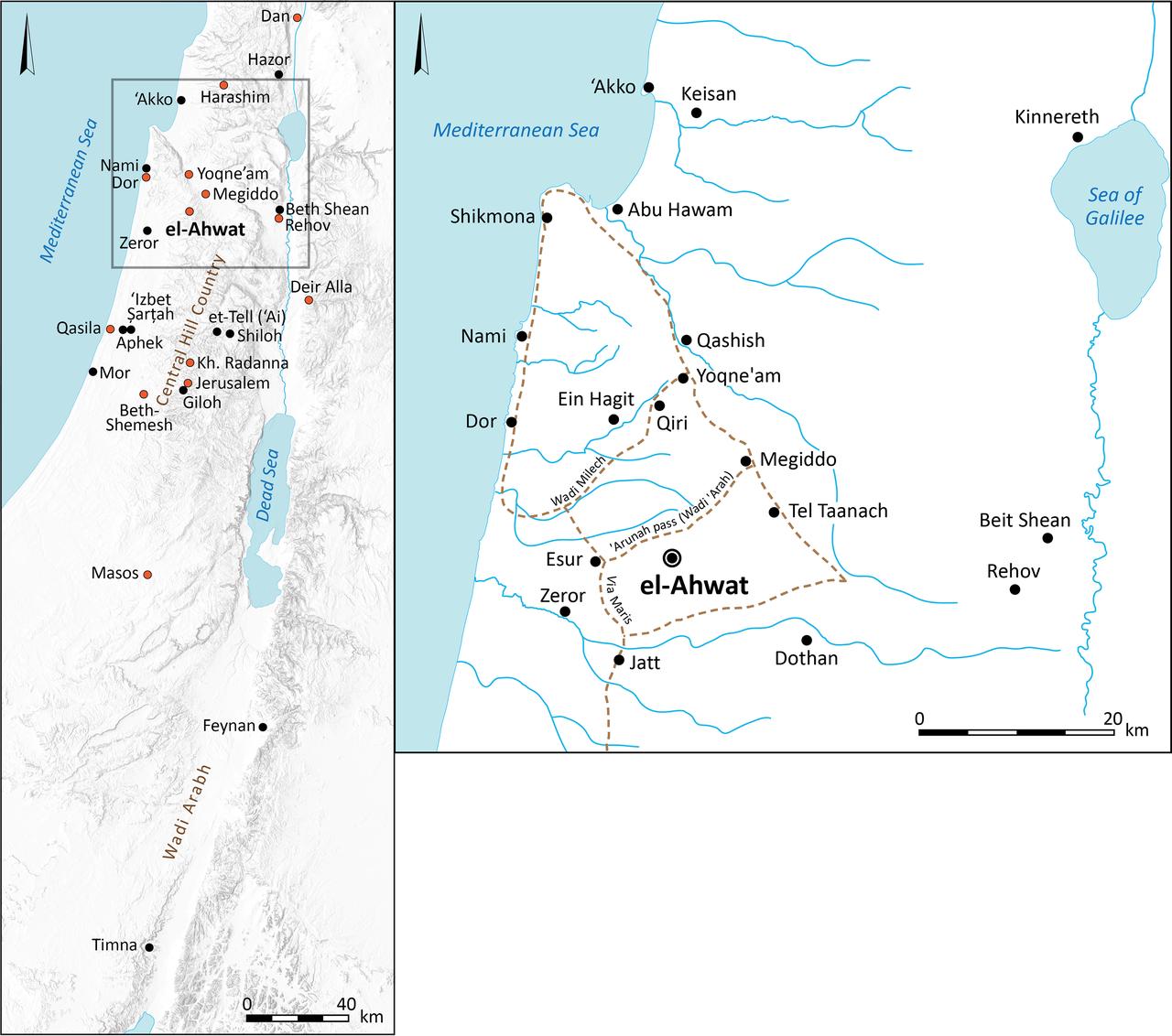

A new study, published in PLOS One on Aug. 7, is the first direct evidence that bronze was produced at the Iron Age I settlement of el-Ahwat, and shows that the metal came from the Arabah copper fields, the valley that runs between modern Israel and Jordan and contains ancient copper deposits at both Faynan and Timna.

The finding challenges the long-held view that bronzeworking in the southern Levant was limited to lowland urban centres and suggests inland copper distribution and local alloying during the early Iron Age.

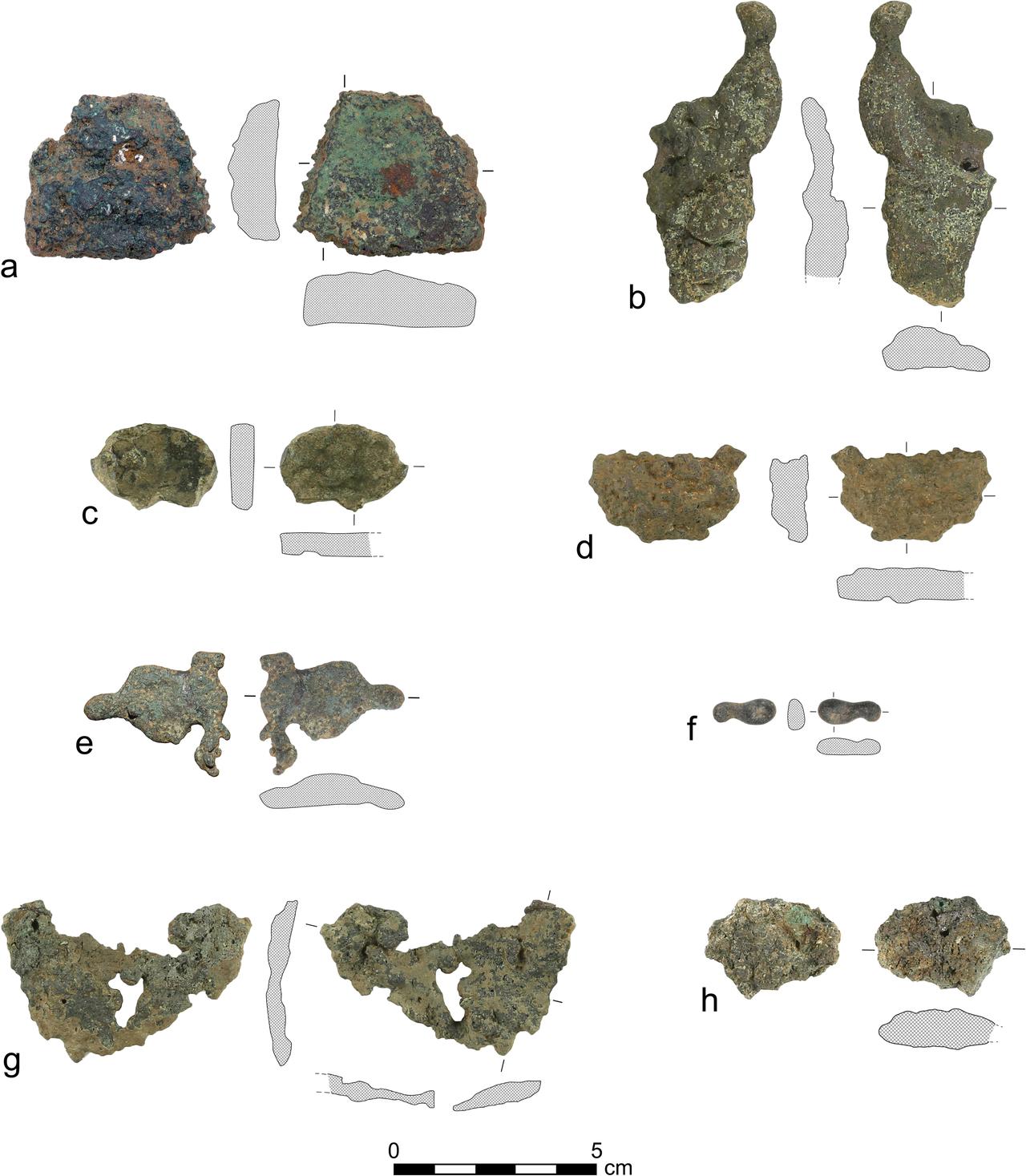

Renewed study of materials recovered from eight excavation seasons found 14 metal fragments and one piece of slag at el-Ahwat; seven of the metal fragments and the slag were subjected to detailed laboratory analysis.

Researchers used optical microscopy and SEM-EDS to look at microstructure, ICP-MS for element chemistry, and MC-ICP-MS for lead isotopes, and they report two clear types of spills—copper and tin-bronze—together with a slag whose composition points to bronze production rather than simple recycling.

Microstructure and chemical signatures show that tin and copper were alloyed at the site rather than merely re-melting scrap. In particular, the team found tin-rich prills trapped in the slag and tin-oxide crystals whose form resembles natural cassiterite, both of which indicate primary alloying of copper with tin rather than household recycling or only remelting cast objects.

The authors state that el-Ahwat “is thus the first site in the region to yield unequivocal evidence for the primary production of bronze through alloying copper with tin.”

Lead isotope results and metallographic markers tie some spills to the Faynan Dolomite Limestone Shale (DLS) ores and others to Timna deposits in the Arabah Valley, and the data are consistent with a mix of sources.

That combination suggests that el-Ahwat was supplied with Arabah copper from more than one mining area, and that those supplies were brought inland rather than being exported only from the coast or to Egypt.

By showing that copper was transported inland and alloyed locally, the study challenges the assumption that Iron Age I bronzeworking in the Central Hill Country was absent or limited to recycling. The results point to a more complex pattern of resource procurement and craft organisation: local communities obtained non-local raw materials, and skilled metalworkers operated within or alongside small settlements, even if the surviving spills indicate uneven quality and some technical inexperience.

The paper links these technological and logistical patterns to broader changes after the Late Bronze Age collapse that reshaped trade and administration in the southern Levant.