Geometry occupied a central place in Islamic civilization, functioning both as a symbolic system and a practical design tool. In Islamic art, where figural representation was often constrained, geometry became a primary mode of expression alongside calligraphy and vegetal ornament.

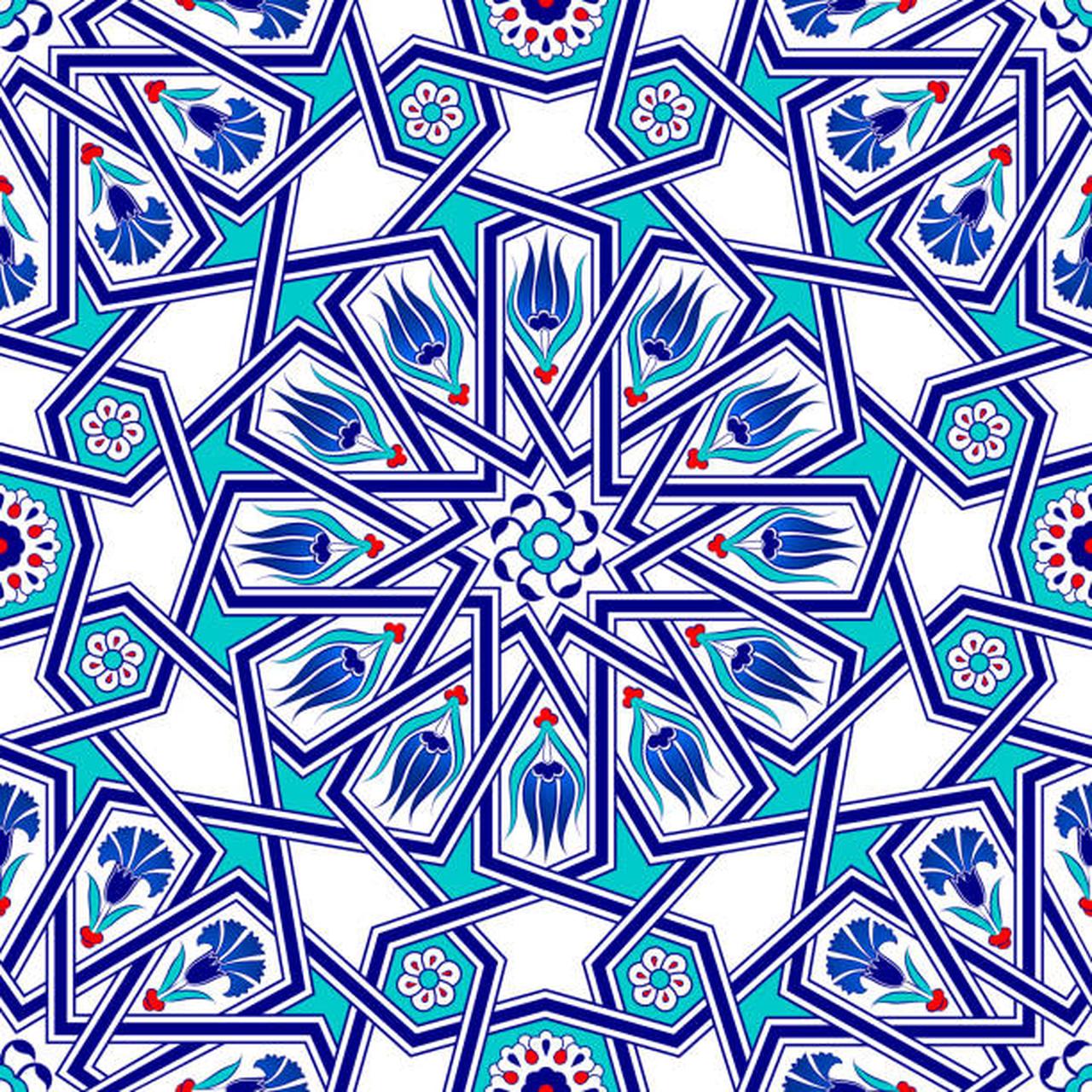

Mahina Reki and Semra Arslan Selcuk describe geometry as a sacred art form rooted in the symbolic unity of the circle, from which triangles, squares, and hexagons are derived. These basic forms generated star polygons and tessellated grids that structured some of the most intricate architectural surfaces in the Islamic world.

Though it was created with only a compass and ruler, the geometric framework reflected the scientific achievements of the Islamic Golden Age.

According to Reki and Selcuk, even the most complex patterns are based on simple grids, revealing a profound understanding of proportion, symmetry, and modularity. This mathematical clarity later found refined expression in Ottoman architecture, where geometry guided not only ornamentation but also spatial planning and structural harmony.

Ottoman geometric design should be understood as a continuation of a long-standing Islamic artistic tradition.

Earlier dynasties had already established a sophisticated geometric vocabulary through sustained experimentation with form and proportion. Seljuk architecture expanded this vocabulary through complex brick-based patterning, while Mamluk architecture emphasized large-scale stellar compositions and rosettes. Across the Islamic world, such geometric systems served as adaptable frameworks that applied to both ornamentation and architectural structures.

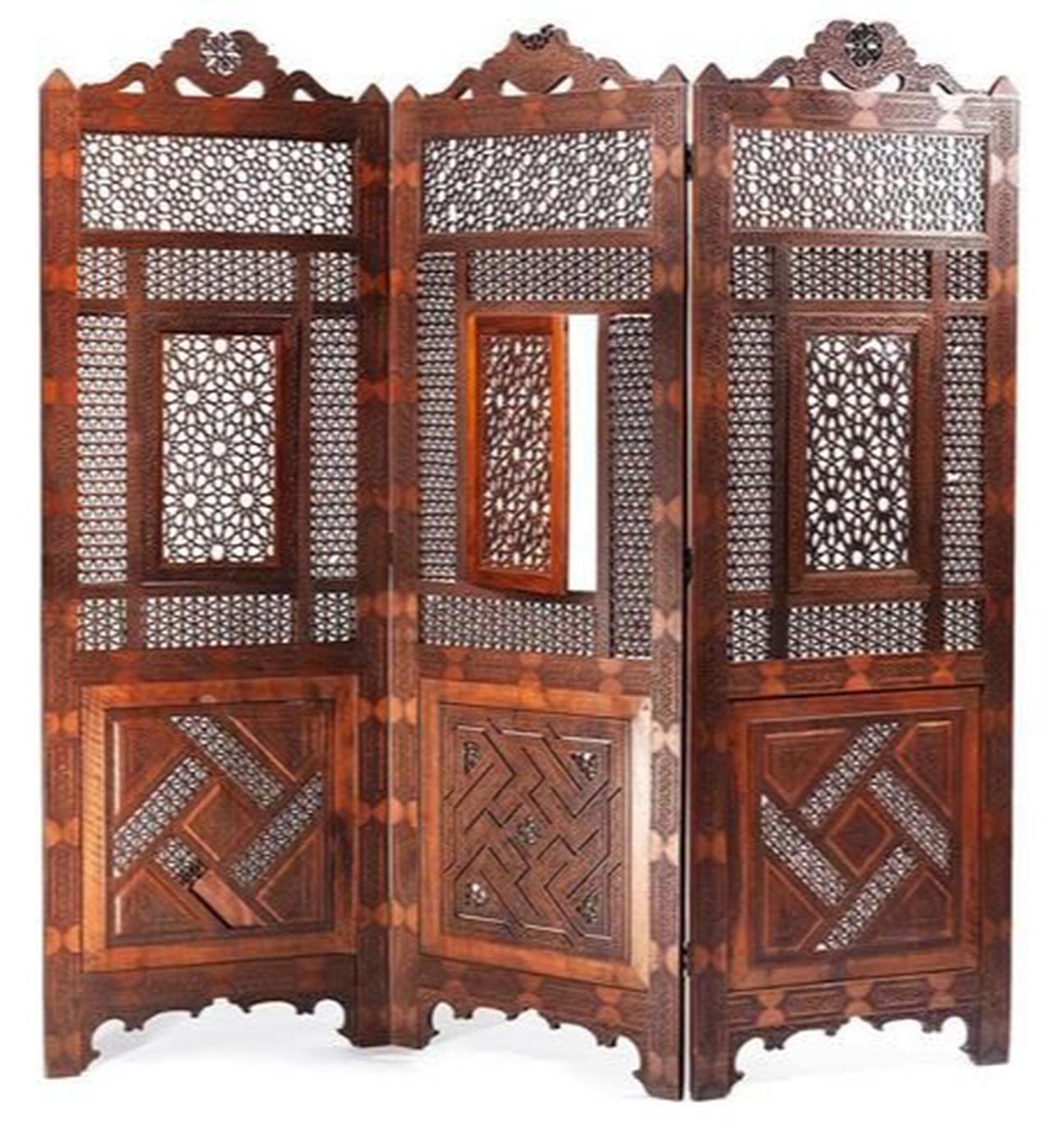

According to Mohamed Enab, the Ottomans did not merely adopt inherited forms but reconfigured them into a coherent imperial aesthetic. Geometry assumed a structural role in architectural design, governing the organization of portals, domes, minbars, and window screens. This integration of geometric order into the fabric of architecture contributed to the clarity, balance, and formal unity characteristic of Ottoman buildings.

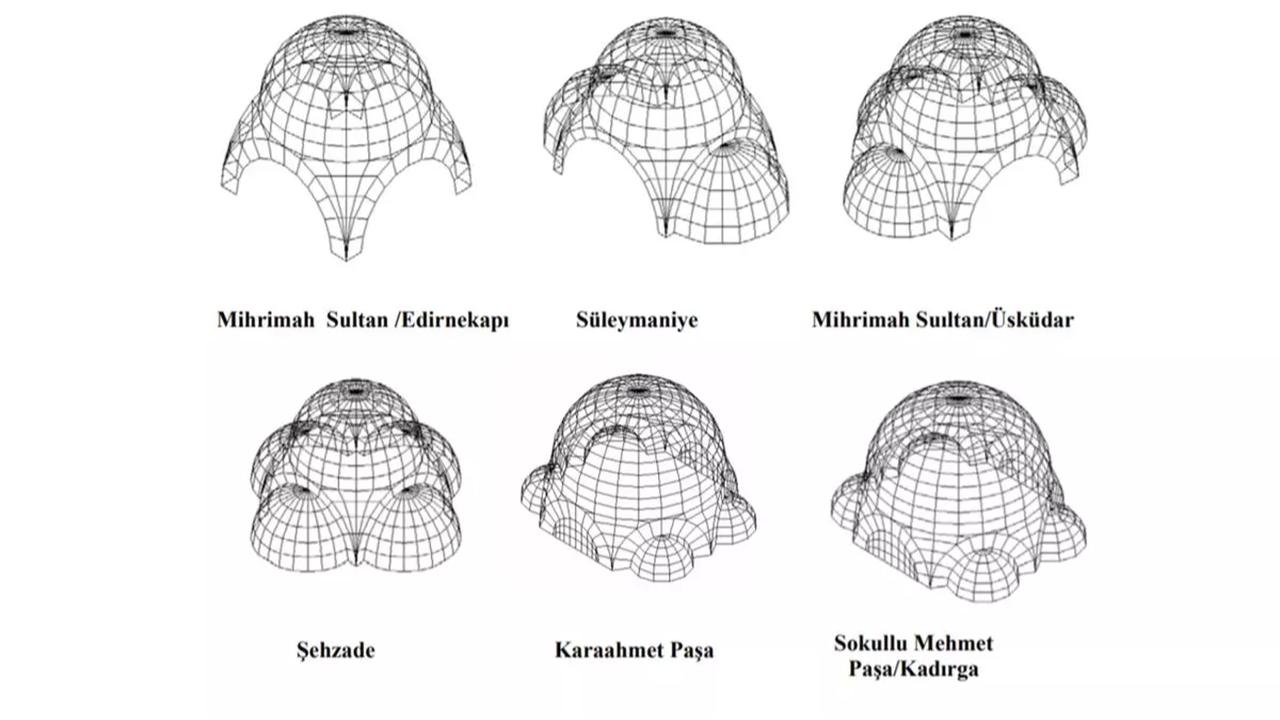

Ottoman architects used geometry as a guiding principle for both structure and ornament. Studies by Reki and Selcuk show that complex Islamic buildings were organized through simple geometric grids and modular divisions, a logic that continued in Ottoman mosque design.

In major works such as the Sehzade and Suleymaniye complexes, Mimar Sinan created a sense of spatial unity through carefully calibrated proportions. While Iznik tiles were largely adorned with floral motifs, geometric patterns continued to play a key architectural role, appearing on doors, window crowns, and carved marble minbars. According to Naser Thabet Al-Mughrabi, Ottoman architects inherited star-based geometric systems from earlier Islamic traditions but used them more selectively, focusing dense geometric decoration on portals, screens, and minbars rather than spreading it across every surface.

The Ottoman court played a decisive role in standardizing geometric and ornamental styles. Aysin Yoltar Yildirim explains that the nakkashane, or court design studio, generated patterns that circulated across multiple media: architecture, ceramics, manuscripts, metalwork, and carpets. Artists such as Baba Nakkas and Nakkas Ali developed inward-turning leaves and geometric medallions that became hallmarks of imperial taste.

Under Mehmed II, the Ottoman court became a cosmopolitan artistic hub. Yıldırım documents how Iranian artists from Shiraz and Tabriz, as well as European figures like Gentile Bellini, were invited to Istanbul. This cross-cultural exchange enriched Ottoman geometry, introducing new compositional strategies and perspectival effects, particularly in illustrated manuscripts.

Architectural decoration in the late fifteenth century reveals the synthesis of geometry and floral motifs. The Tiled Pavilion (Cinili Kosk), built in 1472, exemplifies this fusion. Yıldırım notes that Iranian craftsmen employed the bannai technique to embed calligraphic and geometric tile bands directly into the building’s fabric. Hexagonal and triangular glazed tiles lined the interiors, reinforcing modular geometry at the scale of the wall surface.

Iznik ceramics further disseminated geometric sensibilities. Blue and white wares from the late fifteenth century featured arabesques and medallions closely related to manuscript illuminations. These ceramics were court-sponsored productions designed to complement silver vessels and palace furnishings. Their repetitive motifs and balanced compositions echoed the geometric logic of architectural ornament.

Perforated stone screens, or jalis, represent one of the most functional expressions of geometry. Reki and Selçuk emphasize that jalis served both aesthetic and environmental purposes, filtering light, promoting ventilation, and creating visual privacy. Derived from hexagonal and octagonal grids, these screens demonstrate how simple polygons generate complex visual rhythms.

The Naulakha Pavilion in Lahore Fort, though Mughal, offers a compelling comparative case. Its honeycomb jali panels are based on six-point hexagonal geometry, illustrating the continuity of Islamic geometric principles across empires. Similar hexagonal and octagonal tessellations appear in Ottoman window grilles and courtyard screens, where geometry mediates between interior and exterior space.

Geometry also structured Ottoman military architecture. Studies of Ottoman fortifications highlight how polygonal bastions, radial layouts, and proportional walls reflected mathematical planning. Defensive structures were not only engineered for strength but also composed with geometric clarity, reinforcing the empire’s visual language of order and control.

Urban planning followed similar principles. Gridded streets, axial alignments, and centrally placed monuments organized Ottoman cities into coherent spatial systems. Geometry thus operated at multiple scales, from the ornament of a tile to the layout of an imperial capital.

Ottoman geometry extended beyond architecture into the arts of the book and decorative objects. Yıldırım documents how geometric medallions, star motifs, and interlacing patterns migrated from tilework into manuscript bindings and illuminations. Miniatures from the reigns of Mehmed II and Bayezid II display tiled pavilions with gilded hexagonal surfaces, suggesting that architectural geometry shaped pictorial representation.

Metalwork adopted similar designs. A silver lantern from Mehmed II’s mosque features lobed medallions and pierced arabesques reminiscent of bookbinding motifs. Court-sponsored carpets, particularly the Medallion and Star Usak types, translated geometric medallions into monumental textile form. These carpets required new looms and cartoons, indicating direct court intervention in their production.

Ottoman geometry was not merely an aesthetic choice; it functioned as a marker of imperial identity. By integrating mathematical order into architecture, decoration, and urban design, the Ottomans projected stability, continuity, and divine harmony. The disciplined use of proportion distinguished Ottoman architecture from its predecessors while preserving its Islamic foundations.

The fusion of geometry with floral motifs, calligraphy, and imported artistic traditions produced a uniquely Ottoman visual language. This language balanced inherited Islamic principles with innovation, adapting ancient forms to new political and cultural contexts.

The geometric heritage of the Ottoman Empire endures in contemporary Türkiye’s architectural landscape. From mosque courtyards to museum interiors, geometric patterns continue to shape public space and cultural memory. The Ottoman synthesis of sacred mathematics, artisanal skill, and imperial ambition left a lasting imprint on global architectural history.

As Reki and Selcuk argue, tracing the evolution of geometric patterns reveals not only stylistic change but also intellectual continuity.

The Ottomans did not invent geometry anew; they refined it into a comprehensive design philosophy that united science, spirituality, and statecraft. In doing so, they transformed abstract mathematics into one of the most enduring visual identities of the Islamic world.