New archival research traces how the Japanese ship Heimei-Maru, carrying over a thousand Turkish captives from Siberia, was seized by Greek forces in 1921 and became the focus of complex negotiations involving Japan, Greece, Italy, the League of Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Ottoman Red Crescent.

According to the study, the prisoners on board Heimei-Maru were Ottoman soldiers captured by Russia during World War I and sent to harsh camps across the country, including remote Siberian locations and the island of Nargin in the Caspian Sea, where cold, hunger and disease led to many deaths. The article notes that some Turkish prisoners tried to survive in Moscow and other camps on minimal allowances, while the Ottoman authorities attempted to send material and moral assistance through the Ottoman Red Crescent, known at the time as Hilal-i Ahmer Cemiyeti.

After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty, Japan intervened militarily in Siberia with support from the United States, aiming to contain the spread of communism. Within this framework, Tokyo also tried to take on humanitarian responsibilities related to war prisoners, helping, for example, hundreds of Polish children leave Siberian camps.

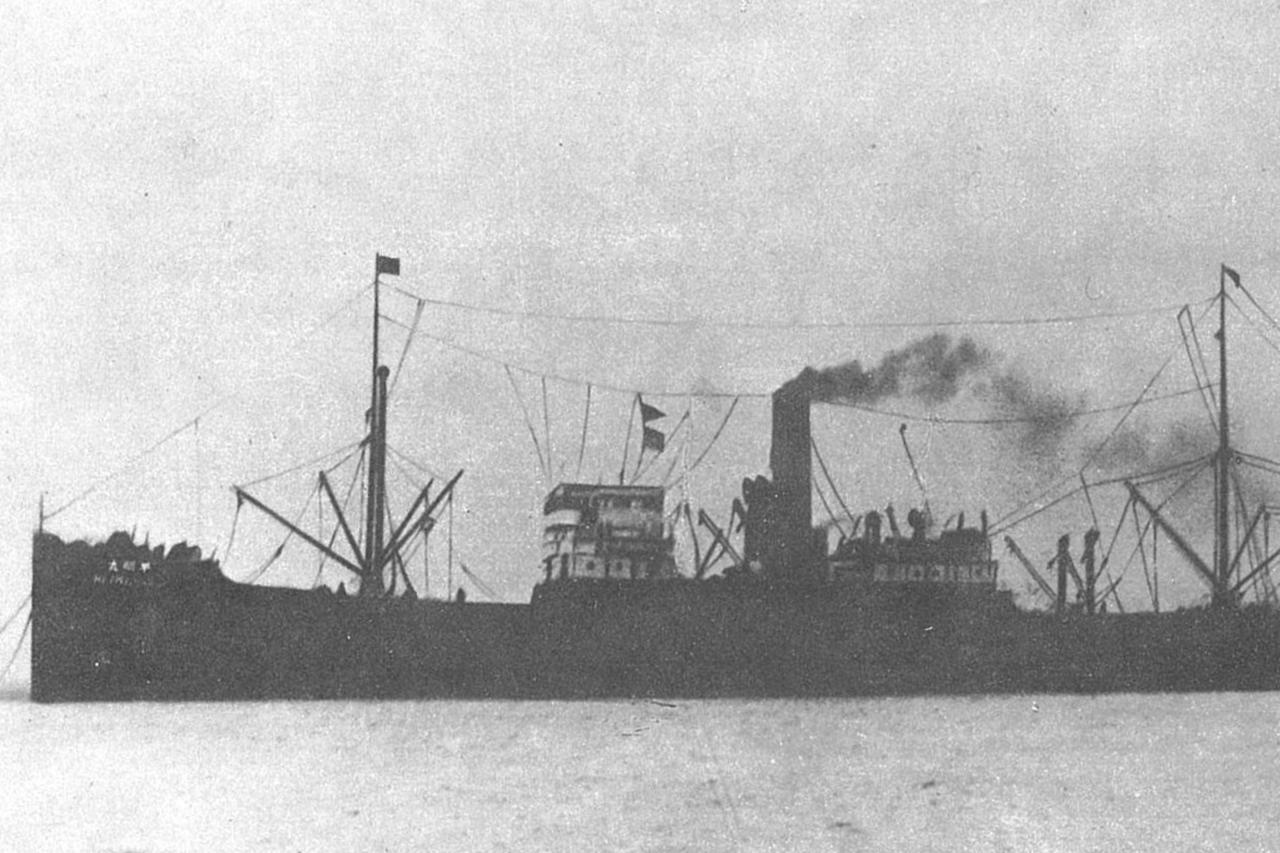

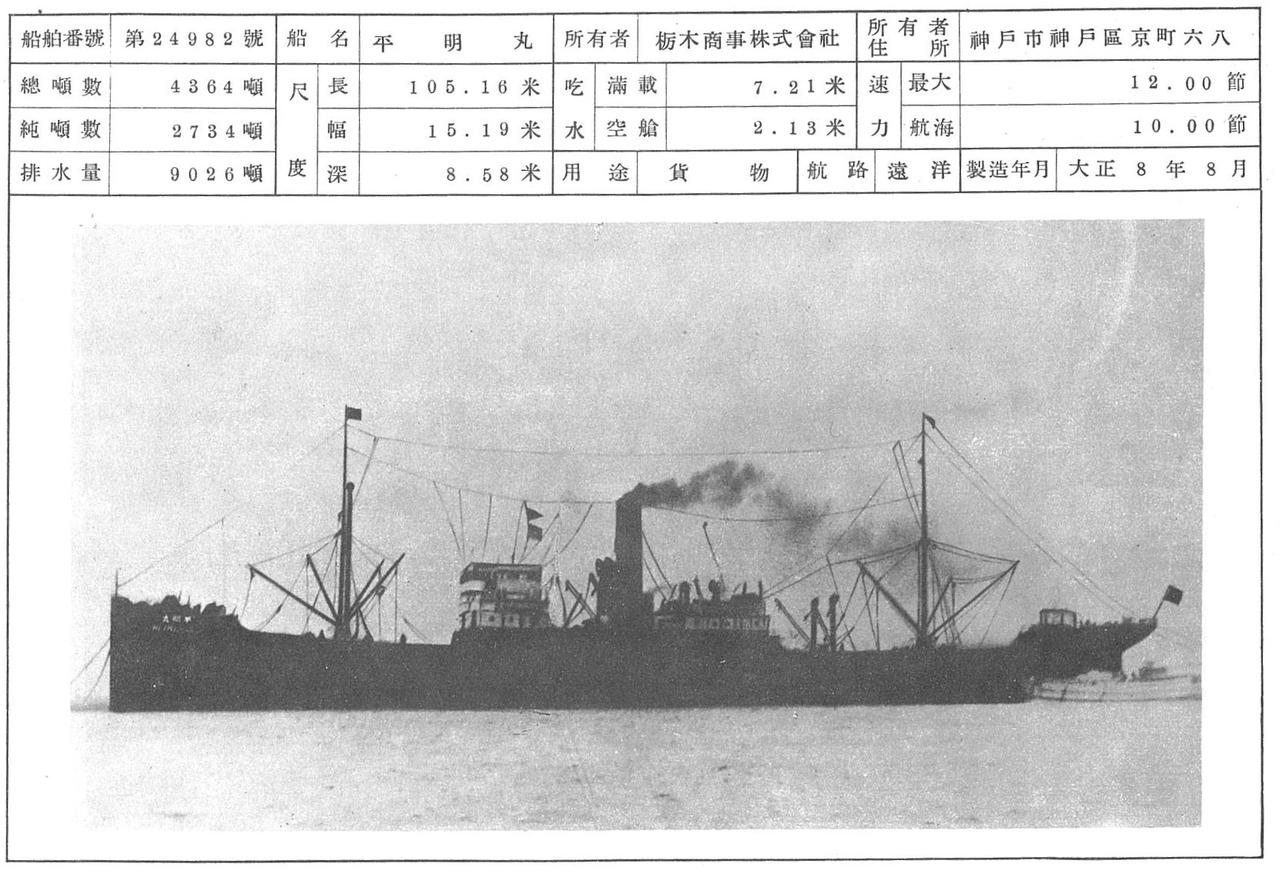

Turkish prisoners were part of the same wider prisoner problem. During the Turkish War of Independence, while fighting continued in Anatolia against Greek forces, the government in Ankara decided to bring home those still held in Siberia. The article states that the Turkish authorities paid the Japanese government 48,000 yen – about 24,000 pounds sterling – to charter the merchant ship Heimei- from Vladivostok to Istanbul with more than 1,000 Turkish prisoners on board.

The ship, sailing under the Japanese flag, set out from Vladivostok and headed towards the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. For many of the prisoners, who had been away from their families for six to eight years, the study stresses that this voyage represented a rare moment of hope after a long period of deprivation.

The journey changed course in April 1921. The article records that on April 3, 1921, while Heimei-Maru was approaching Turkish waters near the Dardanelles close to Canakkale, a Greek naval unit intercepted the ship and diverted it first to Piraeus and then to the island of Midilli (Lesbos).

The Greek government did not treat those on board as ordinary prisoners of war. The study explains that Athens argued the men could return to Anatolia and fight against Greek troops, and therefore insisted that they not be released under normal prisoner-of-war rules. The Greek side also claimed that, because of this classification, it was not violating the Geneva Convention on prisoners.

Conditions on the ship deteriorated quickly. A report by International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) delegate Raymond Schlemmer, cited in the article, describes cramped and airless spaces, especially in the section where women and children stayed. Mothers were said to be so badly nourished that some could not breastfeed their babies. While the report did not identify an epidemic on board, it underlined the lack of food, clean water and medical supplies and warned that the summer heat would make illness more likely.

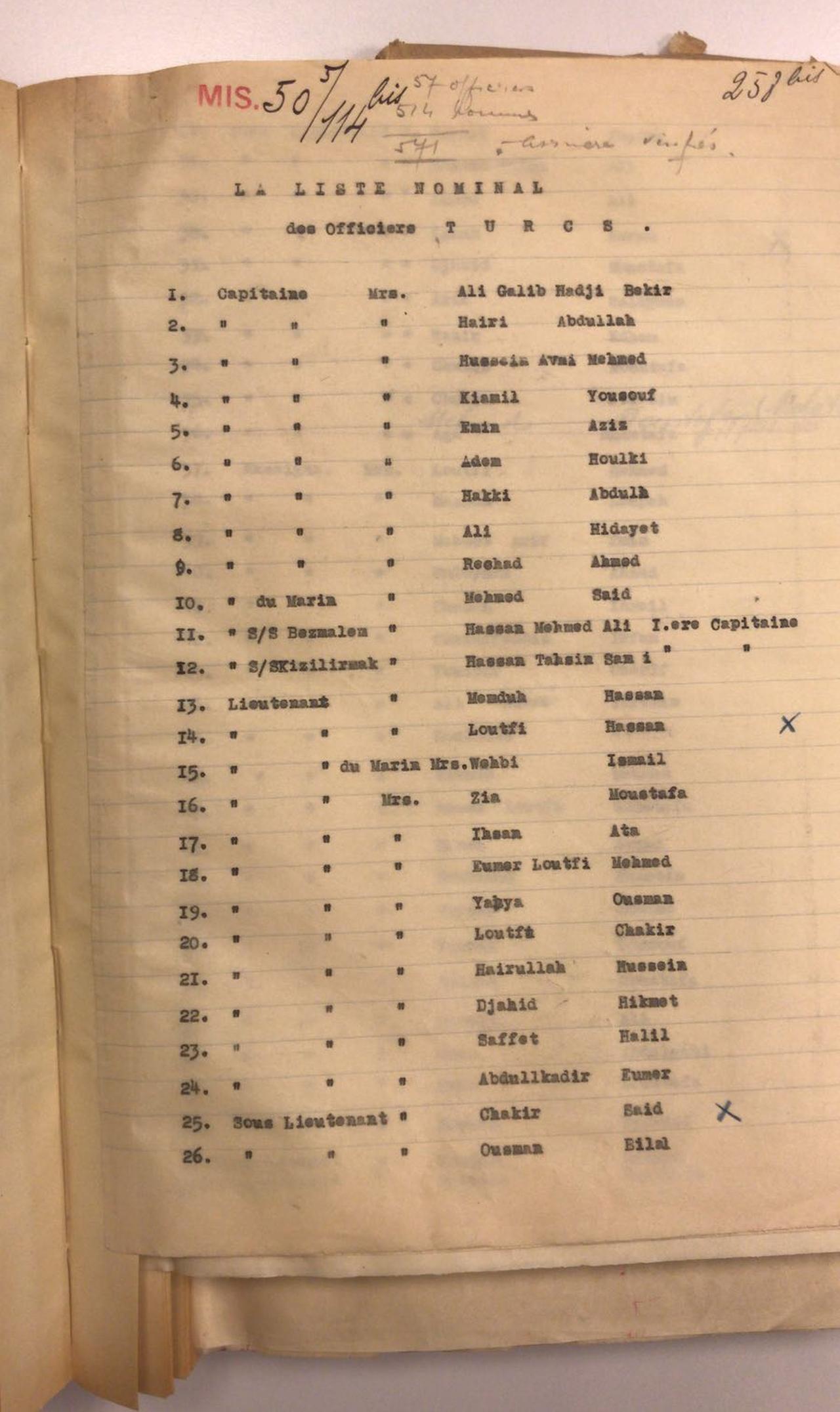

Two passengers – Doctor Yusuf Izzeddin and Lieutenant Ihsan Ata – wrote directly to the president of the League of Nations in June 1921. In their letter, they recalled years of poverty in different parts of Russia and explained that they had left Vladivostok thanks to money sent by the Turkish government. They said that, near Canakkale, a Greek torpedo boat had forced the ship to Piraeus, where the passengers had already been held for more than one and a half months.

The letter listed around 1,000 people on board, including women, children, elderly and disabled men. It stated that they lacked money, tobacco and, most importantly, food, and that some had tried to escape or commit suicide but were stopped. The authors complained that states which claimed to defend “humanity” and “civilisation” remained silent, and wrote: “It is as if we were responsible for the world war, and yet we still cannot return to our homeland.”

The article shows that the Heimei-Maru incident quickly became an international diplomatic issue. The League of Nations appointed the Norwegian explorer and diplomat Fridtjof Nansen, its High Commissioner for refugees, to follow the case. Japan’s representatives, the ICRC and the Ottoman Red Crescent sent multiple notes and telegrams to Athens and other capitals.

The Ottoman Red Crescent notified the ICRC in April 1921 that Greek naval forces had stopped Heimei-Maru near the Dardanelles while it was trying to bring 1,004 Turkish prisoners home. A second telegram reported that the ship and its passengers had been taken to Midilli. The ICRC informed the Japanese embassy in Paris and asked for urgent contact with the Greek authorities.

Japan’s ambassador in Paris told the ICRC that Tokyo had started talks with Athens and was working for the prisoners’ release. The Japanese Imperial High Commission in Istanbul formally reminded the Greek High Commission that Japan had taken on the transport of the prisoners “purely on humanitarian grounds” and requested their unconditional release. Japanese diplomats also underlined that Japan did not intend to take any side in the Turkish War of Independence.

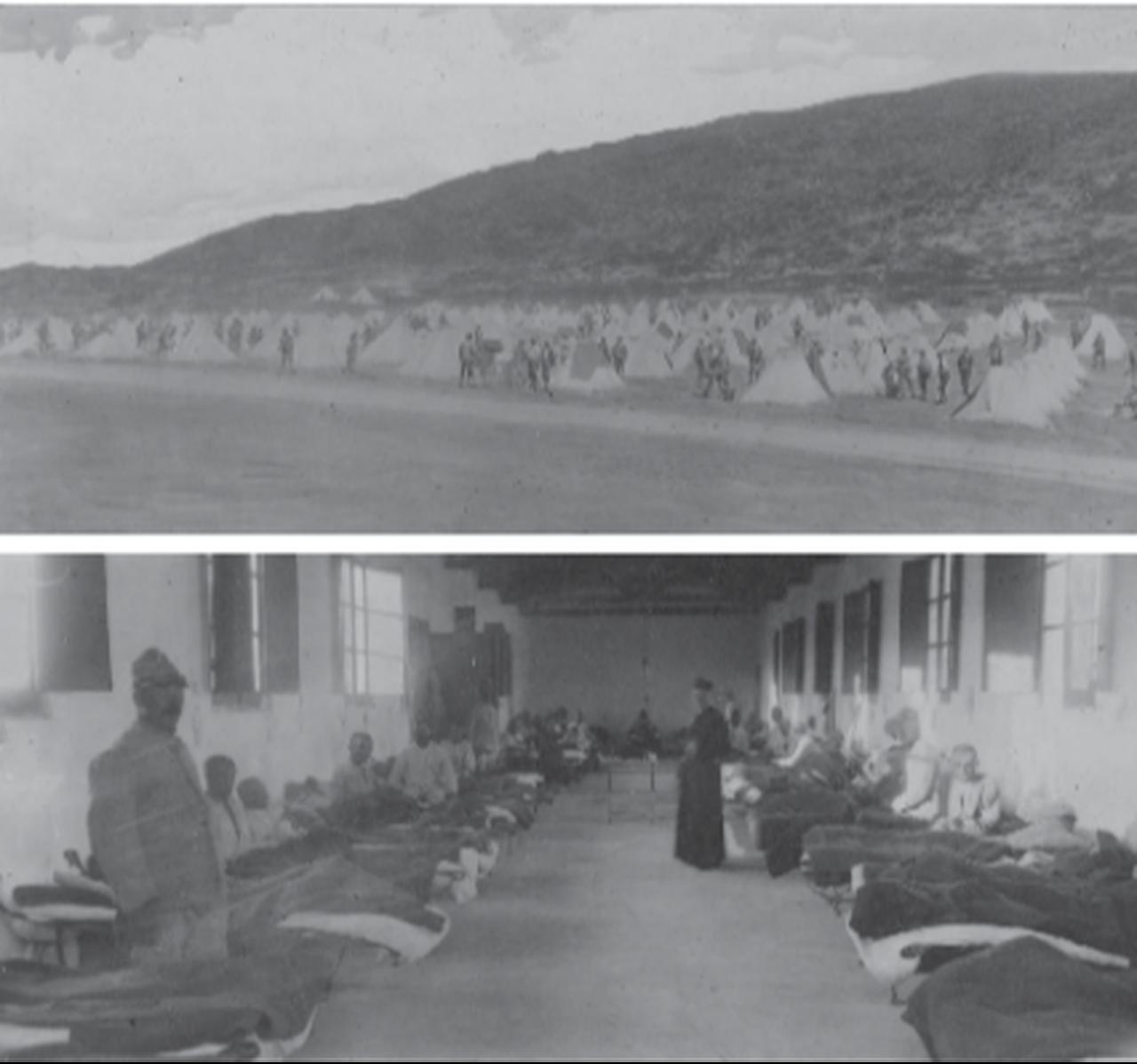

The League of Nations Council discussed the issue in June 1921, and its documents, cited in the study, show that one proposal was to disembark the prisoners in a neutral territory, where they could be supervised without joining the fighting in Anatolia. Nansen suggested that, if Greece was not ready to let the ship go to Istanbul, the prisoners should at least be taken off the vessel and placed in a camp or another suitable location under international observation.

Under pressure, the Greek government eventually allowed about 400 people – mostly women, children and elderly passengers – to travel to Istanbul on a different ship named Olympus. However, approximately 600 men remained under Greek control, and the dispute over their fate continued.

At this stage, the Italian government entered the negotiations. According to correspondence cited in the article, Rome indicated that it was ready to accept the remaining prisoners on Italian soil, on the island of Asinara, where a camp already existed.

The Italian offer came with financial conditions. Initial calculations submitted to the League of Nations mentioned a monthly cost of 700,000 lira to keep around 600 Turkish prisoners on Asinara. Turkish authorities, facing economic collapse, signalled that they were willing to pay but considered the sum too high. League of Nations officials also viewed the figure as excessive and suggested a lower amount.

After further discussion, Italy reduced its demand to 350,000 lira per month. The article notes that the Turkish side still tried to argue for a lower total, calculating daily costs per prisoner and proposing a much smaller monthly bill, but the final arrangement was framed around the higher figure. In October 1921, Ankara gave guarantees that it would pay 350,000 lira per month for the prisoners’ upkeep in Italy, and Asinara became their new place of detention.

Italian authorities later shared spending figures with League officials, stating that more than 400,000 lira had been used between October 1921 and January 1922 for the camp. The article underlines, however, that conditions on Asinara remained difficult and that the Italian government did not show sufficient care for the prisoners’ needs, despite these expenditures.

While the Heimei-Maru passengers were moved off the ship, their captivity did not end immediately. The study describes how international actors kept up their diplomatic efforts. The Ottoman Red Crescent maintained contacts with the League of Nations and the ICRC, stressing that the government in Ankara could not cover open-ended expenses and calling for a solution that would allow the men to return to Istanbul under Allied supervision instead of remaining on Asinara or in Greek hands.

League of Nations documents cited in the article show that the organisation regarded the incident as a test of how new international mechanisms could handle humanitarian questions after World War I. Debates inside the League revolved around issues such as whether the men should be formally defined as prisoners of war, who should bear the financial burden of their internment and how to ensure that any agreement would not affect the ongoing military balance between Türkiye and Greece.

Over many months, these arguments slowed down progress. Greece defended its earlier actions by insisting that Heimei-Maru’s passengers were not prisoners of war and therefore not protected by the Geneva rules, while Japan continued to call for their release on humanitarian grounds and to highlight that Tokyo had chartered the ship with Turkish funds solely to help them go home.

According to the study, it was only after sustained pressure from the League of Nations, the ICRC, the Ottoman Red Crescent and Japanese diplomacy that the Turkish prisoners could finally leave captivity. The article states that, in June 1922, the men were able to return to Istanbul, closing a chapter that had begun with their capture during World War I and had turned into a long diplomatic struggle centred on a single Japanese ship.